[Editor: This article, regarding the Gallipoli campaign (February 1915 to January 1916), during the First World War (1914-1918), was published in The Australasian (Melbourne, Vic.), 27 April 1935. Accompanying the article was a message from Sir William Birdwood.]

Gallipoli

20 years afterwards.

Sir Harry Chauvel Remembers.

Sir William Birdwood’s message

In a letter to the Editor of “The Australasian,” Field-Marshal Sir William Birdwood writes:—

“I wish to assure you how completely I have at heart thoughts of all my old A.I.F. comrades, and that I shall be specially thinking of them on the 25th, when I shall be laying a wreath on the war memorial in London, and attending a commemoration service with the High Commissioner for Australia. I feel, as the years go on, that my feelings for my old comrades become, if possible, greater and even more intimate.”

W Birdwood.

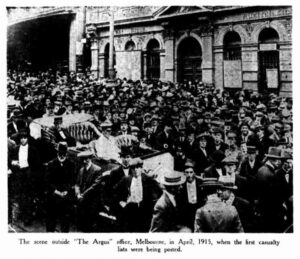

Twenty-one years ago very many Australians would have looked blank or puzzled had they been asked to point out Gallipoli on a map of the world. Probably not one person in the Commonwealth would have been able to state the locality of Suvla Bay. One year later the word Gallipoli had become indelibly scored on the pages of our history. During that year the incredible had become fact. Tremendous events had sent thousands of Australians to arms and had flung them across the world to win fame or death, or both, on a narrow strip of beach or on the face of the cliffs above it, at a spot so remote from their own homes that its name was scarcely known. The story of that landing on April 25, 1915, when the world’s youngest nation won its spurs on the shores of Gallipoli, has been told over and over again in the twenty years that have passed.

Despite the efforts of historians, official and unofficial, however, there will always be something left untold. Every man who set foot ashore on those beaches had his own angle of vision, and has an individual story to tell — if he can be persuaded to speak. One characteristic those Anzacs have in common is their rooted disinclination to talk of their experiences — unless they happened to be humorous. Reminiscences cannot be drawn from an Anzac man, they must be quarried out.

No different from the rest is General Sir Harry Chauvel, G.C.M.G., K.C.B., who commanded the 1st Light Horse Brigade on the peninsula. Sought and found in his official stronghold, and asked to relate some personal experiences on Gallipoli, he was courteously willing to surrender himself to the tender mercies of the interviewer, but, he explained: “I have so little to tell.” Then, after a few moments’ reflection, he added:— “When I think it over, the things that dwell most in my memory are the amusing incidents,” and that is approximately the same answer one would get from 99.5 per cent. of the men who were there.

First impressions

It was not until after dark on May 11, more than a fortnight after the landing, that the transports bearing the 1st Light Horse Brigade arrived off Anzac beach. Sir Harry Chauvel’s first impression of the scene of operations was that they were just in time to participate in a furious battle, the roar of which greeted them from the shore. The whole of the occupied line, he relates, was marked by an unbroken blaze of rifle fire. General Carruthers, of General Birdwood’s divisional staff, who came off to the transport in a launch, was eagerly questioned as to the cause of the demonstration ashore. He calmly replied that there was nothing special on, the racket they heard went on every night, and often all night — things were quite normal. That that riot was normal they were soon to learn for themselves, added Sir Harry Chauvel. Soon after dark each night the Turks would become windy in some part of the line. A small section, perhaps, would open fire, and gradually this would extend until the whole line would become afflicted, and the uproar would be maintained continuously for hours at a time. A curious feature of these nocturnal demonstrations was that very little damage was done unless something moved the artillery to take a hand in the game, then the story became different, and often tragic.

Spartan living

It was not until the morning of May 12 that Sir Harry Chauvel landed with two of his regiments — the third followed later — and made a closer acquaintance with the beauties of Gallipoli. “I left my men in as safe a spot as could be found,” he tells, “and was then conducted by Major-General Sir Alexander Godley to inspect my portion of the line — which Sir Alex. was careful to point out was the most poisonous part of the whole front. He was right, too. It was. It comprised what was then practically the centre and took in Courtney’s Post, Quinn’s Post, and Pope’s Hill. I was to relieve Brigadier-General Trotman and his Royal Naval Brigade, and I was to have my own brigade and Colonel Monash’s 4th Infantry Brigade with which to hold the section.”

This, then, was Sir Harry Chauvel’s introduction to the charms of life on Gallipoli as they were then. He and Sir Alexander Godley made their way up the valley to General Trotman’s headquarters. It was a walk that provided more interest than amusement. “We were fired on all the way,” he says, “in many places we shed our dignity and sprinted round exposed corners with more respect for the watchful Turk than for appearances. Eventually we arrived at a somewhat dissolute-looking rabbit-warren, which served as headquarters for General Trotman and Colonel Monash. There was a notable absence of luxury in their appointments. They were situated in a fold of ground known as Monash Valley, immediately at the foot of Courtney’s Post, and, consequently, within practically a stone’s-throw — or say, a bomb’s-throw — of our front line. The staff signallers and others could congratulate themselves on being reasonably well covered, if not entirely protected, from artillery fire.

Brigade Headquarters

“The view from the window of General Trotman’s dugout was neither extensive nor picturesque. The leading feature of its landscape was a Turkish trench on what was known as the Bloody Angle — a name derived from the literal and not the Australian sense of the word — at a range of less than 400 yards. It was for this reason I found it wiser not to have a light at night. In the morning, however, I found it was practicable to shave close to the window because of the angle of descent from the Turkish trench. That is to say, that any Turk with ambitions to put a bullet through the window would find it necessary to expose himself unduly as a target for our very efficient sharpshooters. However, I occupied this residence until after the Suvla Bay landing, when the New Zealand and Australian division, in which my brigade was included, took over a portion of the new country that had been acquired on the left of old Anzac.”

“It was pleasant,” continued Sir Harry Chauvel, “that Colonel Monash and his brigade major (Major McGlinn) were old friends, and we all settled down together very well. As it was more convenient to handle the whole section as a tactical unit rather than to deal with it by brigades, it was arranged that I should deal direct with the post commanders, irrespective of the brigade to which they belonged, while Colonel Monash was to act as second in command of the section. With the exception of Courtney’s Post, which had always been held by infantry, the men of the two brigades were mixed as required in both other posts. The plan worked excellently, and the two brigades put up a great fight in the general Turkish attack of May 19 and in the attack on Quinn’s Post on May 29.

Grateful Turk

“Talking of May 29,” and here Sir Harry chuckled, “there was an incident arising from the Turkish attack that should be forgotten, but never will be, by those who witnessed it. After we had counter-attacked and regained possession of that section of the front trench that the Turks had occupied, it was discovered that a number of Turks were still in the support trench behind it. This trench had a bomb-proof roof, which prevented our men from getting at the intruders, who also had command of the communicating trench. Several attempts to persuade them to surrender failed until Major Herring hit upon the plan of dangling a handkerchief, hung on a rifle, within their line of vision, as a hint that they should give themselves up. Then some 17 very badly scared Turks filed down the trench to where I was standing. The leading man, seeing my red capband, evidently came to the conclusion that I was someone in authority. He made a significant gesture round his neck with his finger, his eyes obviously inquiring whether his throat was to be cut. To reassure the poor devil I shook him by the hand and passed him down the trench. Instinct, or the look in the next fellow’s eye, warned me that his gratitude could not be fully expressed by a handshake. I had only a moment in which to decide, but, fortunately, I ducked in time, and before he could make a movement in self-defence, the second in command of the post, who was standing immediately beside me, was enthusiastically kissed on both cheeks by the thankful Turk. The major was not pleased, and since I feel I had done him rather a dirty trick, the least I can do to spare his feelings now, is to suppress his name. There are few men who can recall a kiss of 20 years ago, let alone the exact date of the event, but I think the major is an exception.”

What they laughed at

Looking back at the months on Gallipoli, one of the features of the experience that remains in his mind was the remarkable good humour and high spirits of the men in most trying circumstances. They could turn almost anything into a subject for a jest. “I remember,” said Sir Harry, “hearing shrieks of laughter when our staff cook-house was blown to smithereens by a shell. Fortunately, no one was hurt. But the sight of the staff dixies rocketing to the four winds of heaven wrecked the gravity of the spectators. Practically our only relaxation was bathing, and that was carried out under a desultory rifle and artillery fire, except in the early morning, but it was surprising how few were the casualties among the bathers.”

There were no “neck-to-knee” regulations on the beach at Anzac. Men bathed as they were born so that so far as insignia of rank were concerned, all men were — apparently — equal in the water and in the eyes of their fellows. This absence of distinction of rank occasionally led to unexpected results. “One day,” Sir Harry relates, “I was bathing with two or three senior officers, one of whom — he was not an Australian — was in exceptionally good condition. He was especially noticeable because at that time all were more or less attenuated. For some reason this officer, although an active man, and one who did not spare himself, seemed to grow fatter and fatter every day. As we left the water to dry ourselves, an Australian soldier paused to survey our rotund companion with a look of genuine admiration and envy. Then he said with deep conviction: ‘My word, mate! You must have been among the biscuits!’”

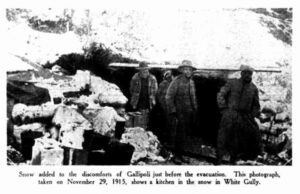

Sir Harry Chauvel pays high tribute to the efficiency of the Quarter-master-General’s department, in which he includes the share contributed by the Royal Navy. “It must be remembered,” he remarks, “that our base was at Alexandria, with a sub-base at Mudros. All supplies for Anzac, including water, which had to be brought in barges, were transported by sea over many submarine infested miles. To my knowledge, no man went without his daily ration and water, although the supply of water on some occasions was no more than a drinking issue — there was occasionally not enough over even to permit of shaving. To those among us who remember the privations of the South African war, this was a marvellous achievement, and one indeed which I believe to be unprecedented in military history.”

An armistice

Asked what he could remember most vividly after 20 years, Sir Harry Chauvel confessed that it was difficult to pick out any particular event. One of the conspicuous days was that of the Armistice with the Turks for the burial of the dead between the lines. What proved to be the most interesting spot that day was in the centre of no man’s land, where a large Union Jack and the Turkish flag flew side by side. Close to these flags gathered important officials of either army. It happened that his guest for the day was Sir Harry’s old friend, the late Sir Charles Ryan — then a colonel in the A.M.C. Sir Charles was wearing on his tunic the ribbons of Turkish medals and decorations he had won when serving with the Turkish Army in the Russo-Turkish war of 1877. The astonishment of the Turks to see an Australian officer wearing these ribbons was most entertaining. He attracted a vast amount of Turkish interest, and alleged that he was conversing with those he encountered in the Turkish language, but on this point Sir Harry permits himself some doubts.

Riding post

After the Suvla Bay landing an unexpected sporting interest was added to the limited relaxation of Gallipoli by the establishment of the horse post between Suvla and Anzac. This post used to leave the bay in the morning and return in the afternoon. The rider did the distance of five miles at full gallop, in view of the enemy and under a long range fire for every yard of the way. On our side, reports Sir Harry, there was always heavy wagering whether the post would get through, and it is probable that Johnny Turk had his bit on as well. The duty was divided between the Australian Light Horse, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles, and the British Yeomanry, each regiment finding a rider for a week alternately. Although it was anything but an enviable duty, the men fairly tumbled over one another in the eagerness to obtain the honour of carrying the post. Strangely enough, despite the chances in favour of the Turks, the post was run for three months before either man or horse received an injury.

Source:

The Australasian (Melbourne, Vic.), 27 April 1935, p. 8 (Metropolitan Edition)

Editor’s notes:

A.I.F. = Australian Imperial Force; the First Australian Imperial Force was created in 1914 to fight in World War One, the Second Australian Imperial Force was created in 1939 to fight in World War Two

Alex. = an abbreviation of the name “Alexander”

A.M.C. = Army Medical Corps

attenuate = to make something weaker or to reduce something in amount, degree, effect, force, size, or value; to make something thinner (especially long and thin); to make something weaker

Australian Light Horse = infantry units which usually operated as mounted infantry, but were also used in cavalry roles; Light Horse units were later repurposed into other roles, such as armoured vehicle units (e.g. the Australian 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment)

See: “Australian Light Horse”, Wikipedia

dixie = an oval-shaped metal cooking pot with lid and carrying-handle for cooking; the lid could be used for baking and the pot was used to brew tea, heat porridge, cook stew or rice, etc. (origin of term, possibly from Hindustani “degchi”, a small pot)

Gallipoli = the Gallipoli peninsula (in western Turkey), which is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey; it was the scene of heavy fighting during the Gallipoli Campaign (February 1915 to January 1916), during the First World War (1914-1918); running along the eastern coast of the Gallipoli peninsula is the Strait of Gallipoli, also known as the Dardanelles (or, the Dardanelles strait)

See: 1) “Gallipoli”, Wikipedia

2) “Gallipoli campaign”, Wikipedia

Harry Chauvel = Sir Henry George Chauvel (1865-1945), an Australian general during the First World War (1914-1918), and Inspector-in-Chief of the Volunteer Defence Corps during the Second World War (1939-1945)

See: 1) A. J. Hill, “Chauvel, Sir Henry George (Harry) (1865–1945)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography, ANU

2) “Harry Chauvel”, Wikipedia

issue = a distribution of provisions (including ammunition clothing, drinking rations, food rations, and equipment) to military personnel or to military units; a distribution of provisions to people or groups (e.g. employees, students); to distribute, provide, supply

K.C.B. = Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

See: “Order of the Bath”, Wikipedia

Monash = Sir John Monash (1865-1931), a civil engineer, and a leading Australian army general during the First World War; he was born in West Melbourne (Vic.) in 1865, and died in Melbourne (Vic.) in 1931

See: 1) Geoffrey Serle, “Sir John Monash (1865–1931)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography

2) “John Monash”, Wikipedia

Mudros = (also spelt: Moudros) a seaside town on the island of Lemnos (Greece); during the Dardanelles Campaign (February 1915 to January 1916), in the First World War (1914-1918), Mudros was used as a base by the Allies

See: “Moudros”, Wikipedia

New Zealand Mounted Rifles = the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, comprised of mounted infantry

See: “NotesAndLinks”, Wikipedia

per cent. = an abbreviation of “per centum” (Latin, meaning “by a hundred”), i.e. an amount, number, or ratio expressed as a fraction of 100; also rendered as “per cent” (without a full stop), “percent”, “pct”, “pc”, “p/c”, or “%” (per cent sign)

Pope’s Hill = a ridge on Gallipoli Peninsula, held by Allied forces during Gallipoli Campaign, in the First World War (1914-1918); it was named after Colonel Harold Pope

See: “Pope’s Hill”, Australian War Memorial, Canberra

Quinn’s Post = a position on Gallipoli Peninsula, held by Allied forces during Gallipoli Campaign, in the First World War (1914-1918); it was named after Major Hugh Quinn

See: 1) “Quinn’s Post”, Australian War Memorial, Canberra

2) “Quinn’s Post Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery”, Wikipedia

red capband = a capband worn on the cap of general staff officers, who would also wear red tabs on their collars (general staff officers in specialist corps or specialist roles could wear capbands and tabs of other colours, e.g. green tabs were worn by intelligence officers)

Royal Navy = the navy of the United Kingdom, i.e. the British navy (it was given the name/title “Royal Navy” by Charles II)

See: “Royal Navy: British naval force”, Encyclopaedia Britannica

the South African war = the Boer War (1899-1902)

Union Jack = the national flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

William Birdwood = Sir William Riddell Birdwood (1865-1951), 1st Baron Birdwood, an officer in the British Army; in December 1914 he was made a Lieutenant General and put in charge of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) during the Gallipoli Campaign (February 1915 to January 1916), during the First World War (1914-1918); promoted to General in October 1917 and given command of the Australian Corps; in May 1918 he was put in charge of the British Fifth Army on the Western Front; promoted to the rank of Field Marshal in 1925; he was born in Kirkee (Bombay Presidency, British India) in 1865, and died in Hampton Court Palace (East Molesey, London, England) in 1951

See: 1) A. J. Hill, “William Riddell (Baron Birdwood) Birdwood (1865–1951)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography

2) “William Birdwood”, Wikipedia

Yeomanry = cavalry units of the British armed forces; after the First World War (1914-1918), Yeomanry units were turned into armoured vehicle units, were repurposed to fulfill other functions, or were disbanded

See: “Yeomanry”, Wikipedia

[Editor: Added a single quotation mark after “among the biscuits!”.]

Leave a Reply