[Editor: This short story by C. A. Jeffries was published in The Lone Hand (Sydney, NSW), May 1907.]

A hero of Babylon.

By C. A. Jeffries.

Ashley awoke with the consciousness that something was not right. Very slowly the walls of the cell took on form and density, and, after considering the plank bed on which he lay, he became dimly conscious of the fact that he had been “run in” again. But there was a curious and unusual stillness through the lock-up.

In the background of his memory there was a recollection of many drinks, of a street row, then vague dreams of frightful uproar, of heavy booming. He dismissed it all with a curse. What was the good of trying to recollect the phantasies of drunkenness? What really mattered was, that he, Cecil W. Ashley, gentleman-of-leisure, sportsman, crack motor-boatist, had once more been locked up for being drunk and disorderly. His trouble was that he could not conceal the fact. Were he less known, he might give a false name and address, pay his fine, and go home with a yarn about the engine of his boat having broken down, and left him drifting about till picked up and towed in by somebody. But he was Cecil Ashley, the popular scapegrace, and well-known motorist. Some beastly paper would chronicle his appearance in the “bird-cage,” and all the city would know.

Now, his wife was pledged to her family to leave him for ever after his next appearance in the police court. Cecil Ashley, who, with all his faults, loved his wife and children, cursed bitterly the wretched spite of Fate. Why had he had that third bottle? Why ——

Then Ashley made the astounding discovery that the door of his cell was not even closed, let alone locked. He peeped out; the passage was empty. He walked forth, and pushing open the door, found himself in the charge-room.

A sergeant of police sat huddled up at his desk, as though asleep. There was a great rent in the wall and roof, through which Ashley could see the sky. A curious feeling of apprehension came over him, and then he suddenly saw the gleam of a great hope. He slid noiselessly to the door, and into the street.

The street was empty. The rubbish of some houses was piled up in the middle of the roadway, and a block away some cottages were burning. But not a soul was in sight.

The first thing that occurred to Ashley was that he had “the horrors,” and that all this was a phantasy of his brain. However, he went out, trying to look unconcerned, and as though he had not escaped from a lock-up.

To Ashley, his brain dazed with the fumes of drink, knowledge was a little slow of gaining. But before an hour he knew that between the time of his arrest — in a state of drunken and stunned stupor, after a street row in Oxford-street — and his waking in a ruined police station, much history had been made. An Asiatic squadron had appeared off Sydney Heads, had destroyed what of the Australian Squadron it encountered, silenced the forts — not without serious loss — and now held the city to ransom. Five millions in gold were demanded within 24 hours, and Sydney was helplessly collecting the money, though the enemy’s effective fighting force was now practically limited to one battleship.

The drunkard made his way to his home at Roslyn Gardens. He found that his wife and children had gone. Sentries at the street corners informed him that all women and children had been removed to the outlying suburbs. But they could give him no idea of where his people could be found, nor how to go about tracing them. Many women and children had been killed, but they knew no names. Had he heard how the ransom money was coming in?

He rushed off to the military headquarters, where he was known. They could not tell him where his family was, nor if any of them had perished. But if they had escaped to the suburbs he need not worry. They would not starve, as all food supplies had been commandeered, and everybody was having rations issued to them.

The evening came with a rush, to end for Ashley a day of aimless, frenzied wandering, tormented with dark reflections. He looked back over the years of his adult life. He remembered his wedding, his first two years of quiet domestic happiness while he toiled for his daily bread. Then came his wife’s unexpected fortune, that gave him the opportunity to indulge his hobby for motor-boating. The alcoholic taint had always been in his blood, but in his hardworking days it had never had the opportunity to develop. Affluence made it flourish. At first there had been whispers, then open regrets, and, finally, the loss of friends, when his name began to appear among the lists of those fined at the police courts for drunkenness and disorderly conduct.

He remembered bitterly how hard his wife had fought to save him. And here he had done an unforgivable thing: had got drunk, been locked up, and lain in a drunken stupor in a police cell while a savage foe threw death and destruction into his home. Oh, if he had only been there to help her and their children to safety!

To Ashley, his mind and nerves over-balanced by the wild debauch he had gone through, and still further strained by the awakening in the midst of such tragic happenings, the position was well-nigh unbearable. He wanted to rush out and do some deed of desperate daring, something amazing and splendid, that would wrap him in a blaze of glory and remove his reproach from him. He wanted to smash that Asiatic warship — to crush it in his hands — to vindicate himself.

And from out of this wildness of thought came an idea. Ashley arose hastily, and rushed to where Colonel Gaw, an old friend, sat puzzling over a mobilisation scheme. He gripped the soldier by the arm, and barked out a flood of quick, short sentences, till he stopped for want of breath. The Colonel took the cigar out of his mouth a moment, and then, replacing it, rang for his motor car. Ten minutes later he was with Ashley in the presence of the Admiral.

“Charlie Sutton’s new motor launch has done 33 knots, your Excellency. Make a hydro-plane of her, load her up with torpedoes, or the most powerful explosives you’ve got, and I’ll drive her at that ship at 40 miles an hour. The plane will lift her nose out, and I’ll soar over the torpedo nets like a bird. Of course the propeller will catch, but it will strip, and the momentum will do the rest. If the engineers say it won’t, well, fit an air propeller, and that will take me right in, and perhaps give me another five miles an hour speed, and I’d like to shake hands with the gunner who’ll pink me before I strike.”

“And what about you?” inquired the Admiral.

“Me! Oh, well, I guess I’ll go with them,” said Ashley grimly.

“Of course you can rely upon the country looking to those you leave behind you.”

“The ransom is due at 5. I shall start at 4. I shall return here at 3.30. I leave you to fix up the details of the boat. I must write some letters.”

“Write them here,” said the Admiral, leading the way to a room fitted up as an office.

Ashley sat down, and wrote feverishly to his wife and to each of his children. While he wrote, from another room came the sound of an organ, and his thoughts kept tune with it. At first sombre music, that breathed inflexible determination, rolled through Ashley’s soul. His heart swelled within him. He, the drunken failure as husband and father, should save his city. If he had brought disgrace on his children’s name in the past, he would leave it covered with glory.

Then the exaltation died out of the music. The melody ran down the trembling vox humana pipe, to a plaintive note of ghostly voices, sobbing in the far distance. And listening, Cecil Ashley felt himself a maudlin humbug. He knew it was not contrition for his wasted life, the wrecked happiness of his wife, and the neglect of his children, that was driving him to this desperate enterprise. It was his vanity!

The music died in silence. The great hall clock chimed the hour of three melodiously. In half an hour he would be on his way to fly, as it were, at the throat of the enemy and, dying, bring to it death. Better to die so, sacrificing his life to save his city, leaving his children a heritage of glory, than to live on and become a drunken wreck.

He sprang up from the table and rushed out to Colonel Gaw, who, seated in a motor car, was waiting for him.

The hydroplane was ready. Fifty feet long and painted the color of the water, it seemed that, at a high speed, the craft must be almost invisible. It was crammed with gun-cotton and dynamite. Charlie Sutton threw away his cigar and explained things to him.

“I think you can escape, old man,” he said to Ashley, laying his hand on his shoulder. “They’ll be on the look-out for fast steamers, craft about 250 feet long that can do 18 or 20 knots an hour, and driven by steam. Anything like that would be stopped as soon as it came in view of the 12-inch guns. They’ve a picket boat at Cremorne and another at Bradley’s that you’ll have to get past. Of course they have others, but those are the only ones which will interfere with you, and they need not worry you. They will not have time.”

“I mustn’t collide with them,” said Ashley.

“Good Lord, no. They’ll have a shot at you, but will never hit. They will never expect, never dream, of a thing that will walk across the water on its stern at 40 miles an hour.”

“Right ho!”

“Now listen,” said Sutton. “You sit on that grating. There’s no need for you to go to glory too. When you strike the torpedo nets let go this strap, and into the water you will slide on the grating. As you slip off she will rise over the nets easily, and then her nose will dip suddenly down through the shifting of the centre of gravity, and bring her smash on to their waterline. If you’re in the water the explosion will kill you, but on that grating you will be safe as the bank. It’s only because the wife howled till I promised her not to, that I’m not coming with you. Send them to ——.”

At Kirribilli Point he was travelling 30 miles an hour and gathering speed. He saw the picket-boat at Cremorne. As he flew, the nose of his boat rose higher out of the water, and, in spite of mufflers, the engine’s clatter became a shrill, awesome shriek. The enemy in their picket-boat sprang to their feet and stared wildly round through their glasses. The sunlight burned on the water between them, and made him invisible.

He was upon them. They reeled past and disappeared. He heard a shot and then a volley. They were signalling danger.

Bradley’s Head loomed ahead and a larger picket-boat. It was on the look-out, but as he made no foam failed to notice him. As Sutton had said, they were looking for a big fast steamer that would smash them in a collision, or an ordinary torpedo boat of 20 knots an hour. An Asiatic officer pointed at him with his glass. Then he was upon them, and as they sprang to their feet he roared past them and round the headland.

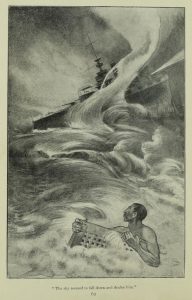

The battleship rushed into view; for to him it seemed as though he stood still and the blurred landscape reeled past. He saw her decks crowded with men, and glasses searching. Then a gun spoke. The side of the ship burst into flame, and the air was full of screaming shells, while the water far astern seethed with them.

Ashley aimed for her centre, just between the two sets of funnels. Then he saw the nets. He felt a bump — he let go. The great ship seemed to suddenly stop rushing at him. He saw agonised faces of terrified men.

The huge battleship, battered beyond recognition, was just turning over — disappearing between gigantic waves. The great waves that had engulphed it rolled over him. Through the bloodstained foam he saw the prow of a boat, kharki uniforms, and — thank God — white faces and outstretched arms. He felt the grip of those Australian hands, he heard the roar of savage joy that greeted the sinking of the battleship, and then the pall of unconsciousness came down on him, and wrapped for many days the man who had tried to die for his vanity’s sake.

Source:

The Lone Hand (Sydney, NSW), May 1907, pp. 61-65

Editor’s notes:

—— = two em dashes (or a variant number of em dashes) can be used to indicate swearing, just as “****”, “$#*!”, “#$@&%*!”, or similar, can indicate swearing (a series of typographical symbols used to indicate profanity is called a “grawlix”); an em dash is an extended dash (also known as an “em rule” or a “horizontal bar”), being a dash which is as wide as the height of the font being used (em dashes can also be used in place of a person’s name, so as to ensure anonymity; or used to indicate an unknown word)

Australian Squadron = a unit of ships of the Royal Navy stationed in Australia in colonial times and for a few years following the federation of the Australian colonies

bird-cage = the lock-up, police cells, a place where alleged criminals are locked up (derived from the standard use of “bird-cage”, or “birdcage”, where birds are locked up in a cage)

Bradley’s = [see: Bradley’s Head]

Bradley’s Head = (also spelt without an apostrophe: Bradleys Head) a headland which protrudes from the northern side of Sydney Harbour; the headland was named after William Bradley (1758-1833), a Royal Navy officer and an early settler in Australia

See: 1) “Bradleys Head”, Wikipedia

2) “Bradleys Head”, Wikipedia

charge-room = the room, or area, in a police station where formal charges are laid against alleged criminals (the same room may also be used for the processing of criminals, regarding fingerprinting, etc.)

Cremorne = a suburb of Sydney, New South Wales; the northern side of Cremorne is adjacent to the waters of Long Bay

See: “Cremorne, New South Wales”, Wikipedia

debauch = debauchery (an act or period of self-indulgence in sensual and/or scandalous pleasures, especially regarding sex and/or the significant consumption of alcohol and/or drugs; a wild and uninhibited party or spree; an orgy)

engulph = an archaic form of “engulf”

glass = an archaic term for “telescope”

the horrors = the DTs: “delirium tremens”, being a violent delirium with tremors that can occur, as withdrawal symptoms, when someone ceases a prolonged period of excessively imbibing alcohol drinks

kharki = an archaic spelling of “khaki”: a tan colour, having a yellowish-brown or a light dusty shade; can also refer to a brownish-green or olive colour; the traditional colour of army uniforms in countries of the British commonwealth (uniforms of khaki colour were used in the British Army since the mid-19th Century, gradually replacing the standard “redcoat” colour, which stood out too much whilst fighting; modern armies now use battle dress with various types of camoflauge)

lock-up = police lock-up, police cell, jail cell, the building where the police cells are located (also spelt “lockup”)

motor car = a car, an automobile

pall = something that cloaks, covers, spreads over, or surrounds an area (or someone, something, or a group) like a dark cloud, cloak, shroud, or veil; a depressing or gloomy atmosphere or mood (can also refer to: a thick cloud of smoke or dust; a feeling of gloom; a negative mood; a heavy cloth draped over a coffin, hearse, or tomb; a coffin; a cloak, a mantle)

phantasies = plural of “phantasy”: an archaic spelling of “fantasy”

phantasy = an archaic spelling of “fantasy”

picket = a person or persons (especially military personnel) placed in an advanced position, so as to give a warning of the presence of an enemy; a sentry, a look-out

pink = to hit, to land a shot (usually with a bullet from a firearm; also, with a cannon shell); to hit, pierce, or prick (especially lightly) with a rapier or sword; to lightly wound someone with a projectile or a sharp-edged weapon

rent = a rip, a split, a tear (especially in an article of clothing); a ripped or torn gap or hole (derived from “rent”, the past tense of “rend”, i.e. to tear or break in a violent manner)

run in = arrested, taken into police custody (usually used in the context of a minor offense); locked up, jailed; an argument, a quarrel (also spelt: run-in)

safe as the bank = very safe, protected and secure (in a reliable manner), as safe as money being held in a bank (also: “safe as the Bank of England”) (similar to the phrase “safe as houses”, regarding financial security in relation to the investment value of a property)

scapegrace = a rascal, a scamp; a mischievous, reckless, or wayward person (usually referring to a male, especially a boy or a young man); a rogue, a scoundrel, an unprincipled and unscrupulous person; someone without grace (i.e. without elegance or virtue); derived from “scape”, an archaic form of “escape”, and “grace”, referring to “the grace of god” (the favour, help, kindness, or love of God), i.e. referring to someone who has escaped from, or avoided, the grace of god

vox humana = (Latin) human voice; a reed stop on a pipe organ (musical instrument) with a tone which is regarded as sounding like a human voice (also known as a “voix humaine”)

See: “Vox humana”, Wikipedia

Leave a Reply