[Editor: This article by P. I. O’Leary was published in the “Books & Bookmen” column in The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 13 June 1940. The article reviews three publications: Revolution, by J. Alex. Allan; Call of the Bush, by Jim Grahame; and The Etched Work of Victor Cobb.]

Two Members of the Australian Choir

J. Alex. Allan and Jim Grahame

It is good to see that other things than the merely destroying ones are being employed to-day. For to create is better than to destroy — a truth that is good ware in any man’s market. And if to nerve a nation in a pass of peril, the assuring sound of some rallying slug-horn, blown Childe Roland-wise, is needed, what is more heart-lifting than the trumpet-tongue of a great poem? What is? Nothing!

Incisive, arresting

There is much of this call to fortitude in “Revolution,” by my lyrical friend, Mr. J. Alex. Allan, whose verse of jewelled phrase has for many years sparkled in the best Australian literary journals. Indeed, the very last poem in this cleanly-presented, tasteful book is a ringing song for France, some of the implications of which may not be acceptable to all in any fuller measure than may some of those in the namepiece, where Revolution, personified, asserts that it is “the breaker of the sword of Cain” … when, all too often, it is the wielder of that homicidal weapon. There are other aspects of Revolution, a deeper ethos, than are dreamt of in the philosophy presented in this opening piece.

These poems are instinct with that incisive, graphic quality that marks all Mr. Allan’s poetry. What could be more arresting than this:

While little bush-sounds snap and crack

Aloof and crepitant?

or this of a submarine:

Assassin of the straits, I glide,

The viper of the seas?

Colorous, many-toned

I fancy I find in these poems a sharpening of that incisive power. There is a tautness that contrasts with a certain richly-pictorial quality in earlier poems of Mr. Allan. But the old phrase-making power is here as well. Thus, Sydney Harbour is described as

The blinding, wrinkled water shot with skiffs.

You try if you can better that.

Perhaps these poems, the best of which, in emotion conveyed and other qualities, is “The Bride Wakes,” are deficient in intensity and undertones. Colour, glow, vibrancy, they have in abundance. They cover an extensive range, are many-noted and, as Mr. Robert Henderson Croll, who writes a Foreword, says, “are nothing if not stirring and vivid.”

Bush-poets all

There are still five or six of them left, and there will be a great vacancy when they go, the so-called “bush-poets,” whose head and front was Lawson — poets who, in their rhymes of simple, away-from-the-city things, of that unique fellow-affection, “mateship,” have registered more of the heart-beats of the genuine Australia than all the poets of another, a more artfully sophisticated mode put together.

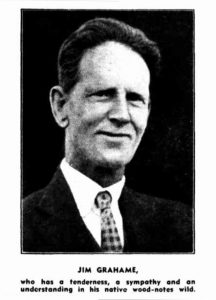

It is the tendency to-day to damn them with a praise altogether too faint. Nevertheless, with a sure instinct, Australia accepts their work as a true voice of our national spirit — if not the only true voice, for our land is many-tongued. Ted Harrington, Tom Tierney, “Brigalow” — here are one or two of them — and Jim Grahame (J. W. Gordon), whom Mr. Walter Jago, in a jerky sort of prelusive appreciation, calls “the logical successor of the Great Poet” (Lawson), is another. That friendly appreciation introduces “Call of the Bush,” a collection of twenty-three of Jim Grahame’s poems.

“Successor of Lawson”

These poems present successful evidence for Mr. Jago’s claim that their author is the logical successor of Lawson. There is the same homely selection of subject; the same, so to say, filial treatment of familiar, everyday things of the bush or the bush-town; the same suggestion of a humorous outlook, implied and pervasive, rather than paraded and particular; and, above all, the same understanding of bush character and the impress upon it of the Outback setting and milieu.

There are, of course, differences of order and medium between a painting by Millet and these unpretentious verses. But something of that essential nobility and inner grandeur which the French painter conveys in his pictures of the French peasants is in those portrayed in these word-canvases by Jim Grahame.

Sincerity and understanding

Simple rhymes, simple measures — there is a tenderness and a sympathy in these native wood-notes wild, in this clear “Call of the Bush.” They ring true. There is none of the almost overpowering force and splendour of great poetry in these artless lines, but they hold something that intimately touches the heart and the mind. They speak in syllables of transparent sincerity and understanding, even if these syllables be not accents of classic art. There are no soaring metaphors in these pages; no epic traffick with the Enchanted Coasts of great poetry. But here are to be seen true, if lowly, unpretentious pictures; facets of the life of this land which are not the less to be prized because they have no dazzling glitter:

I am no classical Red Page rhymester:

I sing my songs to the old bush hand,

The dwellers of bush camp, hut or hovel,

Wielding the axe or the pick and shovel,

By fire or hurricane lamp they read me —

Simple rhymes of our own great land.

Those are the men that clothe and feed me;

They’re the men that can understand.

Jim Grahame can understand, too.

Victor Cobb, artist

“Bob” Croll is becoming almost as prefatory as Shaw himself. He contributes a Foreword to a handsomely got up brochure, setting out etchings, dry-points and mezzotints of Mr. Victor Cobb, whose beautiful work with steel point and acid is so well known. This artist, whose work is represented in the principal Australian galleries and in many private collections, is one of that band of etchers in Australia whose works, as Mr. Croll says, have gained world recognition. Etchings by Mr. Cobb have been reproduced in special numbers of “The Advocate.” These reproductions have been much admired. But the real thing are the etchings themselves.

The appeal of these “is not only to the wealthy connoisseur, but even more directly to the collector with small means, for they meet that great requirement — good art within the reach of all.”

President and Patron

These three publications have been sponsored by the Bread and Cheese Club in furtherance of its admirable policy of assisting Australian Art and Letters.

The good offices of the “Grand Knight Cheese” of that estimable fellowship, Mr. John Kinmont Moir (to whom, incidentally, Mr. Allan dedicates his book, “In Memory of an Old Friendship”), have here, as in so many other directions, been exerted. And not merely his good offices — vague phrase — but, as is characteristic of this genial and kindly presidential holder of the Double Order of the Vat, his practical aid as well.

As one who produced the first Bread and Cheese Club souvenir and edited the “Bread and Cheese Book” — quite a bibliography is now gathering about this alert and practical body — it pleaseth me much here to record the fact.

— P. I. O’L.

Source:

The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 13 June 1940, p. 9

Editor’s notes:

Although this review does not mention the title of the third publication, it is The Etched Work of Victor Cobb (1940), which includes a preface by R. H. Croll.

Bread and Cheese Club = a social club dedicated to the promotion of Australian art and literature, founded in Melbourne in 1938

choir = an organised group of singers, especially one organised in relation to a church or a school, and trained to sing in public or at events; an organised group of people; (in Christian tradition) any of the nine orders of angels (the nine choirs of angels); (Christian phraseology) the dead in Heaven (often people who have died are said to have “joined the heavenly choir”)

Grand Knight Cheese = the title of the president of the Bread and Cheese Club, a social club dedicated to the promotion of Australian art and literature

Outback = remote rural areas; sparsely-inhabited back country; often given as one word and capitalized, “Outback” (variations: out back, outback, out-back, Out Back, Outback)

pleaseth = (archaic) pleases

Red Page = the literature section of The Bulletin (Sydney, NSW), which included literary reviews, poems, and items regarding literature and writers (it was named the “Red Page” as it was published on the inside of the publication’s cover, which was printed on paper of a reddish colour)

[Editor: Changed “away from-the-city things” to “away-from-the-city things” (inserted a hyphen after “away”); added a double quotation mark after “Grand Knight Cheese”.]

Leave a Reply