[Editor: This article, about William Bede Dalley (1831-1888), by Frank Myers, was published in The Lone Hand (Sydney, NSW), May 1907.]

William Bede Dalley.

By Frank Myers.

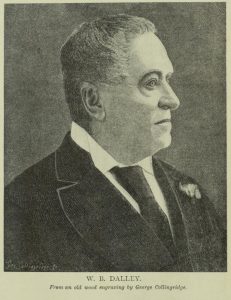

From an old wood engraving by George Collingridge.

We can see him, we can hear his voice. We know so exactly what he would say. It is — “Old boy! and what have you been doing all these years? I tell you, nothing worth listening to has reached us over there for a devil of a time. What has come over you all? What are they doing on the other side of your little planet? All the dear old speakers and singers are with us. William Watson is dumb. Small loss if Alfred Austin were in the same condition. How is it?

Malibran dead,

Duvernay fled,

Taglioni not yet arrived in her stead.

What?”

All the shadows of death could not wither, nor all the custom of immortality stale, his infinite variety.

William Bede Dalley was born amongst the dregs of life in old Sydney, what time she was a Nazareth amongst cities, and her people little less than lepers in the estimation of the world. He was picked up early by the priests, and picked out shortly after, by that great and good man Archbishop Polding. He went glorying through the schools, and came to the Bar (1856) in early manhood with body all lusty, life and soul all glitter and flash, eager to contribute as to share in the zest of life, free as the fairest moon of our “yellow haired September,” of any apprehension of a sombre noon or gloomy eve. But, with will to work, and complex yet harmonious purpose, resolutely held. Law was his staff, politics his sword — the one and the other so garlanded with happy instances, and bright illustrations of all that make up belles lettres in the best sense, as often to be quite unsuspected of any serious intent. Ill fared it, however, with any who held the one or the other in light esteem. “Man of age thou smitest sore,” said many a bewildered antagonist, as he retired from the contest discomforted and ashamed. Dalley’s success in politics brought him to the Premiership of the colony, and prior to that, on the death of Sir James Martin in 1886, he might, had he been so minded, have accepted the Chief Justiceship with the full approval of the whole community.

Dalley wrote much in those days. In Punch, at its best not an unworthy cub of ancient Toby of London. In the Freeman’s Journal, a notable paper in its day; and in the S. M. Herald. Nothing that will live and shine like radium; but a good deal that might very well be recovered and republished. Not, however, with intent to establish or perpetuate the man’s fame. That must rest on deeds done. Nor yet to carry him farther into the heart of hearts of those who knew him — that were impossible. It is rather the unwritten, unrecorded things we would desire to snatch out of the mildew of the past; the record of days and nights when Dalley and Aspinall met; with sparks struck out as from steel on steel; the wit, the repartee, the revelry that must have been; for these twain were fit to stand and to shine in any company this world ever saw. It is lost. The mildew has it, and will waste and rot it away.

I knew Dalley first in the early ’eighties. His career at the Bar was practically closed then, and it was generally held that politics would know him no more. He had by strenuous labor, and without any of the meaner thrift, made for himself a competency. He had married the daughter of Captain Long, a wealthy old merchant seaman. His wife had died, and on the day of her death he had left that fair house, builded after his own designs, on the South Head Cape, overlooking the harbor and ocean, never to return. It was the sepulchre of all his best hopes of happiness. With his family he was in retirement or retreat at Moss Vale, when a confused murmur of decadence and despondency from the whole State came to him as a summons to be obeyed. He closed his books, he put off his mourning, he girded on his sword once more, and came down to the battle. That movement sadly shortened his days, but completed and crowned his fame. The record of that time is written in the chronicles thereof. Its one feature, so eminent as to dwarf all else to insignificance, is the formation and despatch of the Soudan contingent. That for good or bad — and there be those to-day who unreservedly damn it as wholly bad — lifted William Bede Dalley into the recognition of the whole world, placed him in position to claim any honor or distinction in the gift of the Crown, and took him in the end of things to the Empire’s high sanctuary of old St. Paul’s. It was the idea of his mind. It was the work of his hands. How that mind wrought, how those hands labored in that time is known but to few. Dalley, whom some, having never known him, affect to despise and to contemn as dilettante, a poseur, a muddler in politics, a flaneur in literature, was seen then working, as it is given to few men to work, and with a will, a heartiness, a geniality, against which all opposition was vain.

He was making for us “a festival of chivalry and patriotism.” I verily believe he had more pleasure in minting that phrase than in accepting (the only reward he would accept) a Privy Councillorship.

He was building for himself at that time another home, at Manly by the sea — a quaint place, Norman castle built on to Swiss chalet; it is in some sort a symbolical monument to him still. He himself was curiously compounded. Strength to grasp every occasion and use it to the full, blent with self-doubt, and a tendency to lean on and even take from others, wholly unnecessary and absurd.

We had a visitor then, G. A. Sala, and we arranged to feast him, as was meet. Dalley should speak for us, who else? I saw him many times while (sad waste of labor) he was preparing himself to speak, looking up quotations over the whole range of literature, loading himself with a charge, that should be re-echoed in the applausive thunder of the gods. That speech fell flat. We were dismayed, he disheartened. G. A. Sala got up, and after telling us how his main staple was rather of malt than of meal, dealt out the malt delightfully. We made the roof ring, but still with a sub-consciousness of sadness, for our own chief had failed us. Then old John Robertson, bluff, gruff, and uncompromising, made occasion for explanation, if not apology or defence, and Dalley was up, and rapier out like lightning. No quotations or set phrases then. He dashed into the moment of gloom like a comet, and in ten minutes the table was all ablaze and a-rattle. Sala’s eyes grew wide, he rubbed his chin, muttered “das ist wunderbar,” and when it was ended, stared wonderingly at the little man, as one who had found “a bigger brother belonga-me,” than he had deemed to exist in this world.

Spontaneity was Dalley’s strength, and he knew it not. A marvellous great good-heartedness his chief characteristic, and of that he was unconscious. I met him once in the main street of the Manly village. He was riding his charger (commissioned in the contingent time). As we talked together, a tall, gaunt man, limped by on a crutch. “Hello, old boy! What’s wrong?”

“Broke my leg in a quarry, sir.”

“That’s bad, bad. How do you pull through?”

“Middlin’; can’t complain. My mates, sir, you see, stand by me.”

“That’s good. Let me be one of your mates, too. With love, old boy, with love.”

I think the love was remembered longer than the fiver.

“We were talking about that passage in Dante,” said he the next minute. “Oh, Tennyson prigged it beyond all doubt; come up and I will look it out.”

So we went up and compared the “Nessun Maggior dolore” and the rest of it with the “In Memoriam” half-admitted crib, and then we mourned over the pathos, and gloried in the strength of that drift of fiery rain, lashing incessantly the doomed, devoted bodies of poor Paolo and Francesca, and he introduced me to “The Sick King in Bokhara,” which heretofore I had missed — and we glanced at the “Merman,” and he murmured against “that damned old priest with his bell, who could not let the poor girl alone with her happiness,” and we agreed that old Tennyson had after all some redeeming features, and that “Will Waterproof” was well-nigh as splendid a piece of optimism as “John Gilpin.” Then back to the great ghost-raisers — Euripides and Sophocles and Dante; and agreement once more that Milton’s “Nativity Hymn” was amongst the few things which really do seem half divine. Last, jumping zig-zag from height to height, we alighted on Browning’s “Childe Roland,” and went understandingly, realising as we went, through every phase of that weird and wonderful, but utterly inconsequential imagery.

Twilight came upon us thus, and we were silent a while, looking out to the ocean. When next he spoke it was out of the depths. “There is nothing in it, old boy. I have gone some way, you may go farther; God knows! But the little house, the little wife, the little child. There’s nothing else —. Where the devil is that fellow with the claret? I shall have to turn Savage Landor with him — you remember that story? Oh, my God; those poor violets!”

I did not see his face just then. It is not seemly to be curious when great minds, broken up, hurl back their emotions with an effort.

He entertained much on those days; on Sunday evenings always. And never-to-be-forgotten are those festivals of all dainty, delicate eating, royal drinking; and later, talk, ranging from Rabelais to the Antigone or the Johannian gospel. Noctes ambrosianæ, every one. The man’s whole soul would lighten on his face, over which the shadow of death had already fallen. He would make all the old warriors Australia had bred or known rise again for us, and show how each one had in his time said or done something fit to be remembered, and so justified his claim to a place with the Immortals. “That hoary old lion of the University,” Charles Badham; Bolding, “that dear saint”; Wentworth — “some of you fellows ought to paint old Wentworth as he was on that election day; I can see him now on the rickety hustings, roaring out to the roaring mob — ‘Martin is in and Terry is out. Shout! ye blackguards; shout!’;” William McLeay — “he made some deuced good wine;” Vaughan — “an ascetic at home, but a Prince of the Church abroad, and nobody understood him.”

All the old school of Bohemians he had known and befriended. One (let him be called Jobson). “Poor old Jobson! He bothered me a good deal; must be on the butts of half-a-dozen cheque books. It came at last to two births and three funerals in one year. Then, God was good to me. He took Jobson.”

My last association with him was over a sad and cruel affair. “Mount Rennie” will bring it all back to those who know, and those who do not will do well to rest untroubled in their ignorance. Suffice, that it was determined in Sydney to avenge a great crime with an over-shadowing horror of retribution, and this some of us endeavored to avert. With Sir Henry Parkes, and the Anglican and Roman Catholic Archbishops, Dalley approached the Governor, Lord Carrington, and endeavored to show him the limitations both righteousness and mercy would place on hot and unconsidering vengeance. It was all in vain. Let it lapse. I think it enabled Death, now grimly determined, to come some steps nearer his destined prey. “No use, no use,” said Dalley; “the man is adamant.” And then, “I must get home; this has shaken me.”

The shadows closed fast after that cruel day. He was hag-ridden with insomnia. If he ventured abroad, it was to render some little services of graceful speech to his church. He was a devoted Catholic, though quite untouched by any of the bigotry or rancor inseparable in common minds from strongly-held denominational religious principles. Francis of Assisi, the Catholic, and Bezer of Geneva, the Calvinist, though their times were of blood and fire, of rack and cord, could, and did, each live and die a perfect gentleman, lovable and loving, and beloved by all. Even so, William Bede Dalley, amongst the little bitternesses which frequently beset him.

It is almost incomprehensible that Nature did not deal kindlier with him in his last days; but these things are beyond us. When on a full glad October day in Melbourne here, news came of his passing, there was sudden hush and sense of chill amongst a very merry party.

“He rests,” we said; “his rest is sweet.”

And silence followed, and we wept.

And still he rests; or if that happy Limbo Dante created have indeed an existence, does there, with great and glorious souls, hold converse high. Nor can anyone of us entertain a higher hope, however humbly held, than that, when our time of passing comes, we also may meet him there, and there with him and them abide.

Source:

The Lone Hand (Sydney, NSW), May 1907, pp. 1-4

Editor’s notes:

abroad = to go out of doors, to go out and about (distinct from the meaning of to travel to a foreign country or to another continent)

Alfred Austin = (1835-1913), an English poet

See: “Alfred Austin”, Wikipedia

Aspinall = Butler Cole Aspinall (1830-1875), a barrister, journalist, and politician; he was born in Liverpool (England) in 1830, came to Australia in 1854, returned to the UK in 1871/72, and died in England in 1875

See: 1) Joanne Richardson, “Aspinall, Butler Cole (1830–1875)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography

2) “Butler Cole Aspinall”, Wikipedia

belles lettres = (French, meaning “beautiful letters”, i.e. “fine writing”) works of literature that are regarded as a fine art, being written works (especially drama, fiction, and poetry) which have an aesthetic or artistic nature, rather than having an informative purpose (especially regarding works which are entertaining, refined, sophisticated, well-styled, and aesthetically pleasing), distinct from serious, scientific, and technical works; can also refer to: writings on literary subject matter, especially essays (also spelt with a hyphen: belles-lettres); (as a dismissive term) literature which is considered lightweight, overly refined, and having little substantive worth (also spelt with a hyphen: belles-lettres)

blent = blended (past tense of “blend”)

Bohemian = someone who is socially unconventional in appearance and/or behaviour, who lives in an informal manner, especially someone who is involved in the arts (authors, musicians, painters, poets, etc.); an artistic type who does not conform to society’s norms; can also refer to a citizen or resident of Bohemia; (archaic) a Gypsy or Romani; of or relating to a Bohemian, a group or class of Bohemians, or the Bohemian lifestyle

Browning = Robert Browning (1812-1889) an English poet and playwright

See: “Robert Browning”, Wikipedia

Browning’s “Childe Roland” = the poem “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”, written by the English poet Robert Browning (1812-1889)

See: 1) Robert Browning, “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”, Bartleby

2) “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”, Wikipedia

builded = an archaic form of “built”

contemn = to regard with contempt or disdain; to treat with contempt or disdain; scorn

Dante = Durante degli Alighieri (circa 1265-1321), known as Dante, an Italian poet (best known for his epic poem “Divine Comedy”)

See: “Dante Alighieri”, Wikipedia

das ist wunderbar = (German) “that is wonderful”

deuced = a euphemism for “damned” (a mild exclamatory oath)

determined = decided, resolved (can also mean: of firm decision, of unwavering mind, resolute, unwavering; to have decided to do something, especially in the face of difficulties)

dilettante = an amateur or dabbler; someone who engages in an area or field as a hobby, as an amusement, or as a matter of casual or superficial interest, and whose knowledge and understanding of it is not likely to be high (compared to a professional, who is paid to work in an area or field, with appropriately training, and a high level of knowledge and understanding)

even so = (archaic) similarly; in the same manner; of the same nature

fiver = five pound note (British Imperial currency); five pounds (£5)

flaneur = (French) a dawdler, idler, loafer, loiterer; someone who wanders in an aimless manner; someone who travels at a slow pace; someone who ambles or slowly strolls about in an idle manner

Francis of Assisi = (ca. 1182-1226), born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, an Italian monk and founder of the Franciscan Order (the Order of Friars Minor); he was made a saint in 1228

See: “Francis of Assisi”, Wikipedia

full glad = fully pleasing, very pleasing (a reference to something which can give someone much happiness or much pleasure)

G. A. Sala = George Augustus Henry Fairfield Sala (1828-1895), an English author and journalist

See: “George Augustus Sala”, Wikipedia

gird = surround; to encircle or bind with a band or belt; to fasten or secure with a band or belt (used in the expression “gird your loins”, i.e. to put on or tighten your belt, in order to prepare for an effort needing endurance or strength)

hag-ridden = harassed, tormented, or worried, as if cursed by a hag (a witch); afflicted or overly-burdened by, or suffering from, anxieties, fears, or nightmares; harassed, tormented, or worried by a woman (normally from a male viewpoint, especially used in a humorous or teasing manner) (also spelt as one word: hagridden)

Henry Parkes = Sir Henry Parkes (1815-1896), the owner and editor of The Empire newspaper (Sydney), and Premier of New South Wales for five separate terms (1872-1875, 1877, 1878-1883, 1887-1889, 1889-1891)

See: 1) A. W. Martin, “Parkes, Sir Henry (1815–1896)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography

2) “Henry Parkes”, Wikipedia

hoary = a descriptive term for someone or something which is old or ancient; someone with grey or white hair; something grey or white in colour

hustings = a temporary platform upon which candidates were nominated for Parliament, and from which candidates would give a campaign speech to voters; in modern times, to be “on the hustings” refers to candidates campaigning for election to political office (especially for a seat in parliament); derived from the Old English term (of Old Norse origin) “husting”, meaning “house thing” (a “thing” being an assembly or parliament)

See: “Husting”, Wikipedia

the Immortals = the elite bodyguard of the Persian Emperor; the “Ten Thousand Immortals”, an elite unit of 10,000 men who fought for the Persian Empire; the gods of Greek and Roman mythology; the great men, famous people, or leading lights of a people or nation (who are regarded as having achieved a form of immortality by being remembered forever, or for a very long time)

James Martin = Sir James Martin (1820-1886), politician and judge; Premier of New South Wales (1863-1865, 1866-1868, 1870-1872), and Chief Justice of New South Wales (1873-1886); he was born in Midleton (Cork, Ireland) in 1820, and died in Potts Point (Sydney, NSW) in 1886

See: 1) Bede Nairn, “Martin, Sir James (1820–1886)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography

2) “James Martin (Australian politician)”, Wikipedia

Long = William Alexander Long (1839-1915), a merchant, politician, and race-horse owner; he was born in Sydney (NSW) in 1839, and died in Lewisham (Sydney, NSW) in 1915

See: 1) Bede Nairn, “Long, William Alexander (1839–1915)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography

2) “William Long (New South Wales politician)”, Wikipedia

Marion Crawford = Francis Marion Crawford (1854-1909), an Italian-American author; he was born in Tuscany (Italy) to American parents, lived for many years in the USA, and died in Sorrento (Italy) in 1909

See: “Francis Marion Crawford”, Wikipedia

meet = (archaic) suitable, fit, or proper; also, something having the proper dimensions, or being made to fit; can also mean mild or gentle

middlin’ = (vernacular) middling: medium, moderate, or about average in quality, quantity, or size; mediocre, ordinary; used in the phrase “fair to middling” (commonly used regarding being mediocre in health)

Milton = John Milton (1608-1674), an English author and poet, who became blind later in life; author of the epic poem, Paradise Lost (1667)

See: “John Milton”, Wikipedia

Mount Rennie = a reference to a criminal case involving twelve young men of the Waterloo Push (a street gang) who were charged in 1886 with having raped Mary Jane Hicks; four of the accused were hung, whilst most of the others received long prison sentences (several were sentenced to life imprisonment), with two being acquitted (the case was widely referred to by contemporary newspapers as the Mount Rennie Outrage)

pathos = compassion or pity; or an experience, or a work of art, that evokes feelings of compassion or pity

Polding = John Bede Polding (1794-1877), a Catholic archbishop; he was born in Liverpool (England) in 1794, came to Australia in 1835, and died in Darlinghurst (Sydney, NSW) in 1877

See: 1) Bede Nairn, “Polding, John Bede (1794–1877)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography

2) “John Bede Polding”, Wikipedia

sepulchre = a repository for the dead; a burial place, grave, crypt, or tomb; also a receptacle for sacred relics, especially those placed in an altar (also spelt: sepulcher)

S. M. Herald = The Sydney Morning Herald newspaper (Sydney, NSW)

Soudan contingent = a contingent of 758 soldiers sent by the colony of New South Wales to aid the British military in the Anglo-Sudan War (1885), also known as the Mahdist War (“Soudan” is an archaic spelling of “Sudan”)

See: 1) “Sudan (New South Wales Contingent) March-June 1885”, Australian War Memorial

2) “New South Wales Contingent”, Wikipedia

3) “Mahdist War”, Wikipedia

St. Paul’s = (in the context of London, England) St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, named after Saint Paul (a disciple of Jesus Christ)

See: “St Paul’s Cathedral”, Wikipedia

Tennyson = Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892), an English poet

See: “Alfred, Lord Tennyson”, Wikipedia

twain = (archaic) two (from the Old English word “twegen”, meaning “two”); especially known for the phrase “never the twain shall meet” (from the line “Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet”, as used by the poet Rudyard Kipling, at the start of the poem “The Ballad of East and West”, which was included in Barrack-room Ballads and Other Verses, 1892)

verily = certainly; truly; in truth

Wentworth = William Charles Wentworth (1790-1872), an Australian explorer, lawyer, poet, and politician

See: 1) Michael Persse, “Wentworth, William Charles (1790–1872)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography

2) “William Wentworth”, Wikipedia

ye = (archaic; dialectal) you (still in use in some places, e.g. in Cornwall, Ireland, Newfoundland, and Northern England; it can used as either the singular or plural form of “you”, although the plural form is the more common usage)

[Editor: Changed “retired from the contets” to “retired from the contest”.]

Leave a Reply