[Editor: This obituary for P. I. O’Leary was published in the “Books & Bookmen” section of the The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 2 August 1944.]

The Open Road and the Inky Way

Patrick Ignatius O’Leary (1888-1944)

Rover-poet and Catholic journalist

A cripple and his books

But words are but an artist’s instruments, the vehicles of a man’s thoughts, a man’s beliefs. Who, then, was the man? Who was P. I. O’L.? For thousands, he was a legend and an oracle, masked behind four letters of the alphabet, an automaton of words, remote, impersonal. He was a man, who lived intensely, who knew the bitter and the sweet, who created beauty, who died young — Patrick Ignatius O’Leary.

He was born at Georgetown, South Australia, in the year 1888, the son of an Irish school-teacher and the fourth in a family of nine children. The Irish patriot and reformer, Michael Davitt, who was visiting Australia, was god-father at his baptism.

Born slightly crippled, he was unable to walk until eight years of age. His father, a man of learning and a lover of books, naturally lavished his care and affection on the invalid and very early initiated the youngster into the beauties of literature. He spent his childhood in the company of the masters — reading, reading, reading. His playmates were the sailormen of Conrad, the adventurers of Stevenson and he was soon at home among the poets and “Old Shake,” as he often called him.

When his father died in 1900, he had found his feet, and the miracle of walking — a discovery he was never to forget. He became a keen cricketer (with someone to run for him), and a good horseman, but he loved to walk and walk.

The family moved to Port Pirrie. The moods of the sea and the sailing ships stirred his imagination. His Conrad came alive and his Stevenson spurred him to a youthful adventure. When fourteen years of age, he and a pal stowed away on a wind-jammer, bound for America, but they were caught just in the nick of time. What would have been the destiny of P. I. O’L., had the escapade succeeded?

Along the track

Sometime in the first decade of the century, the O’Learys moved to Broken Hill. In the silver city, he spent the ten most impressionable years of his life. It was a raw and turbulent town of miners, shearers, drovers, sundowners, industrial unrest and social radicalism. The youth, Pat O’Leary, was caught up in the Utopian idealism of the radicals and in the blunt Australian nationalism, with the “Bulletin” as its bible. But it was the romance and fellowship of the outback that first fired his poet’s soul.

He learnt to know and love the bush, the freedom of the open road, the blazing Australian skies. He often took to the track and humped his “bluey” from Adelaide to Broken Hill, from the Hill all the way to Melbourne. He was at heart a sundowner, in tune with the great loneliness of the plains, the dusty roads and the little hot towns of the bush. He was a philosopher of mateship, one of the last of the tribe of Henry Lawson.

When the city caught and tried to cage him, he never lost his nostalgia for his days along the road:

For me the grass and the spaces, the highway and the sky,

The blithe birds in the hedgerows, the sun and the wind that’s high,

The mounting swell of a green wave white-flowering into foam,

The hill-rise and the farm lights a-glimmering in the gloam;The youth of the world at morning, the soft east kindling fires,

The far spread of great country, the flash of distant spires,

The meal by the flank of the trailing, draughts had in the wayside inns,

The deep content of the open, the stars as the night begins. …

He was rent collector, book-keeper, rouseabout, sundowner, shearer’s hand, social agitator, strike-leader, reporter, editor, poet, critic. His literary genius first found expression in short pars and verses, contributed to the ‘‘Bulletin”; he received his first lessons in journalism from H. H. Champion, the English radical then visiting Australia; his first job on the staff of the “Barrier Miner.”

Hummocky Hill

In 1912, at the age of 24, Patrick O’Leary married Mary Teresa Slattery at the Broken Hill Cathedral. They settled in Adelaide, where he combined odd jobs with his free-lancing, including periods as an insurance agent and as a reporter for the Adelaide “Advertiser.” It was the time of the great “Conscription” controversy. The “Advertiser” was vigorously campaigning for “Yes.” P. I. O’L. mounted a box, in front of the office, and harangued the passing crowd in favour of “No.” He was looking for a job.

He moved to Hummocky Hill, known to-day as Wyalla, a new settlement established by Broken Hill Pty. Ltd., with which he had obtained a position as time-clerk. P. I. O’L. was one of the founders of the local library and the rifle club, and became a leader in civic and sporting affairs.

But his restless, creative spirit fretted among the figures, and towards the close of the war years he came to Melbourne in search of literary life and recognition. He brought with him a bundle of poems and sent them to various newspapers and periodicals. The response was cold and discouraging.

He was reduced to running a stall at the Western market, selling polish for silver-ware. But let him tell in his own words the thoughts that thronged his mind, when busy commercial Melbourne passed him by:

I Came Into the Market

I came into the market

With songs, in my satchel borne,

Of white moons moving at midnight

And yellow suns mounting at morn.And I had catches of wonder,

Whose magic was like a spell;

But you had cattle, and wains of grain,

And merchantry to sell.None heeded my wares and, hungry

For that I had solden none,

I took my songs of the tall moon,

I took my songs of the sun;And I passed, sad, out of the city —

Barren of pence or pride —

Woe kept step on the left of me,

And Want on the other side.Your horn’d bulls brought you money

In mountains, and your brown grain

Poured wealth to your clinking coffers,

In glittering, golden rain.But my songs brought me sorrow,

and sombreness never told;

But still they are bright with dreaming,

Outgleaming your huckster gold.And all your cattle are vanished,

And all your grain is fled;

Your cattle that went to the shambles,

Your grain long baked to bread.And your loud bulls never bellow,

And your grain is dust on grass,

But the glory of my sad singing,

Will never, never pass.

At “The Advocate”

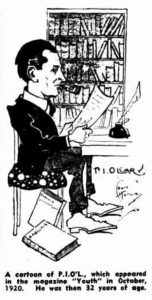

“The Advocate” discerned his literary genius in a number of contributions he made to its pages and he was invited to join its staff in the year 1920. From that day until his death, P. L O’L. was associated with The Advocate Press and its various publications.

He was a rare phenomenon in journalism, a writer of astonishing virtuosity. There was ink in his blood and the clicking of the machines was music to his ears. He could turn his pen at a moment’s notice to every phase of the work — as reporter, editor, sub-editor, literary critic, book-reviewer, editorial writer, all at the same time. He wrote under a variety of pseudonyms — “Historicus,” “M,” “Francis Davitt,” as well as P. I. O’L.

His unfailing, encyclopædic memory dispensed with reference books and filing indices. For cabinets, he used large envelopes, stuffed with cuttings, while from the mysterious depths of his pockets, he could always draw inexhaustible literary riches, carefully salvaged from his reading. He could tear the heart of the world’s news from the overseas exchanges in a matter of minutes, mint the treasures of foreign periodicals by turning the pages, dash off bright, intelligent comments on the happenings of the day. His news paragraphs and commentaries at their best were sharp, crystalline and intensely personal, reflecting the early influence of the “Bulletin.”

His personality and style were strongly impressed on the pages of “The Advocate” for over twenty years, giving them an originality and prestige, which made the paper widely known and eagerly sought after, not only throughout Australia, but in Ireland, England and America. P. I. O’L. was a one-man magazine. There will never be another.

The golden twenties

The golden years of P. I. O’L. were the twenties, when the “Literary Page” of “The Advocate” reached the height of its excellence and was known and quoted the world over. From its cockpit, he surveyed week by week the literature of the English-speaking world and corresponded with writers and poets in many lands.

The week before he died, he left to his son, Rev. Kevin O’Leary, of the Salesian Congregation, a bundle of letters from great literary figures in England, Ireland and America. But his special mission was the fostering of Australian art and letters. His authority as a constructive critic grew with the years, and young writers from every part of Australia sought his advice and encouragement. His greatest discovery — and one of which he was justly proud — was the remarkable New Zealand poet, Eileen Duggan. It was P. L O’L. who first acclaimed her to the world.

He not only edited “The Advocate,” almost single-handed, but regularly wrote for the “Red Page” of the “Bulletin,” and contributed literary essays to the “Southern Cross,” Adelaide, and to a number of short-lived literary periodicals. In his early days, he wrote for the “Lone Hand” and the “Triad,” and, on his coming to Melbourne, for the magazine of the moment, “Youth.”

Meanwhile, he was a familiar and welcome figure in the literary clubs and art salons of Bohemian Melbourne and the friend of C. J. Dennis, Bernard O’Dowd, “Furnley Maurice,” the Palmers, and many others.

At the height of his fame, he refused an offer from Sir Keith Murdoch to join the literary staff of the “Herald.”

P. I. O’L., the poet

P. I. O’L. was essentially a poet. His easy-going, casual exterior masked a sensitive, dreaming spirit. He seldom revealed himself in normal social contact and then only in unguarded snatches of conversation. But his sad poetry reveals the inner man. He saw beyond, sensed the wonder of things, grasped the romance of ordinary life, felt, like Lawson, for the “Faces in the Street.”

There is surely an echo of Lawson in these verses:

And if it’s Romance you seek, then stay,

For it presses about you in square and street;

Around the corner and over the way,

Where the hearts of the cities’ myriads beat.

Where the smiles and tears of God’s humans be;

Where glad lips laugh, and where bright eyes glance —

There you will come on the true Faerie;

There within call is Earth’s best Romance.

The lines are from “Romance,” the title poem of his only book of verse, printed, in a limited edition, in 1921.

His early work is in the ballade and lyric style of the “Bulletin” tradition, then followed a period, strongly influenced by Francis Thompson, finally a phase in the style of Gerard Manley Hopkins. But his later work is buried in newspaper files; most of it has never been published.

The two O’Learys

There were really two O’Learys — Pat O’Leary, the radical and the rover of the open road, and P. I. O’L., the literary critic and Catholic journalist. The two were reconciled only in death.

The first was of the Lawsonian tradition, with its warm humanity, egalitarian, contemptuous of wealth and privilege, cynical of pose and affectation. He never quite lost the social attitudes of his Broken Hill days.

He idealised the code of mateship, that first flowering of Australian folkways, which grew up among the men of the bush in the eighties after the failure of the land struggles. Mateship was largely a class-conscious expression of frustrated social idealism. For P. I. O’L., with his poet’s insight, it was a surging of the spirit of fraternity among the exploited men without land.

This side of O’Leary breathed an intense Australianism. It glowed like a fire — a camp fire — and his mates were Henry Lawson, Francis Adams, Roderic Quinn, Victor Daley, and the “Bulletin” poets of Australian nationalism.

Catholic and Irish

The other O’Leary, P. I. O’L., the literacy critic and Catholic writer, developed when he came to Melbourne. Until then, it would seem, his Catholic mind was largely dormant, his Catholicism a co-mingling of Catholic instincts and Irish nationalism. He was Irish and Catholic, but there was little specifically Catholic intellectual formation. Certainly there is nothing of the Catholic spirit and insight in his book, “Romance.”

But, when he came to “The Advocate,” it seems, a new world opened to his mind. With books, periodicals and newspapers flowing to his table from the whole Catholic world, his essentially Catholic spirit was awakened, and his mind was steeped in Catholic thought. He began to see life and reality in a new light and to undergo a certain process of re-education.

But it was a little too late. The ghost of his other self haunted his footsteps, calling him back to the open road. To the vagabond poet, it was irresistible, but it brought him sorrow, poverty and despair. He called himself a “derelict of dreams” in a powerful and poignantly autobiographical poem:

A leper in the lazarette of life,

A broken sword-blade in a martial strife,

Am I

Who, hungry, cold and harried, bed me here

Beneath the arrowy stars whose searchant, clear

Eyes spy

The flawed and windowed armour I have on

And cast their vengeant, silver shafts thereon.My thin cheeks gather greyness, and my feet

Have lost the lusty rhythm of their beat;

My heart

Is an old broken cobblestone, and Woe

With iron sabots over it does go.

No art

May picture the pitiless misery washing me

Within the hopeless waters of its sea.

His experiences touched strange depths in his soul and those who bore him up and gave solace to his spirit were the Catholic mystics — St. John of the Cross, St. Teresa of Avila, the poets of misfortune, Francis Thompson, James Clarence Mangan and French Bohemian mystics, Charles Peguy, Leon Bloy. In them, he found a community of soul, a saving mateship in his life’s decline.

Literary will and testament

The last literary will and testament of P. I. O’L. appeared on this page the week before he died — “out of other days … memory lays invisible hands.” It was an affirmation of Christian values, an act of trust and abandonment to Providence, a gesture of sorrowful farewell to his readers. The death of a fond sister called up his yesterdays and the pageant of his childhood unfolded in words that echoed a requiem. He recalled the family Rosary, the little school-house, the old songs, the guests from the roads and their travellers’ tales, the magic of rainy days, the games in the moonlight.

After his life’s wandering, he affirmed the primacy of God and simple things, reserving his last attack for Wordsworth and his “unintelligible world.” The erstwhile radical, who would have changed the world, affirmed its purpose in the divine scheme of things, even though man has done his best (or worst) to make it unintelligible. But in the midst of his burden of sorrow and remembrance, he heard death’s shuffling footsteps:

“We know we have here but a passing tenement. Our stay at the longest is but a span. Sooner or later comes the summons and the melancholy hic jacet is written above us.”

And when the manuscript was finished, he handed it to his son and casually remarked: “I’ll never write again.”

P. I. O’L. was dead, and death waited quietly for the soul of Patrick Ignatius O’Leary. They buried him by the side of the road, out beyond the town, near a wattle tree, under three tall gums. There was a high wind rustling their leaves. And the sun. He would have asked no more. P. I. O’L. had found peace of body and soul.

“For me the grass and the spaces, the highway and the sky, The blithe birds in the hedgerows, the sun and the wind that’s high …”

— James G. Murtagh

Source:

The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 2 August 1944, pp. 9-10

Editor’s notes:

This article states that “The Irish patriot and reformer, Michael Davitt, who was visiting Australia, was god-father at his baptism.” It should be noted that whilst Michael Davitt had intended to tour Australia in 1885, his tour of Australia and New Zealand did not occur until 1895, following which he wrote a book about his experiences, observations, and opinions, entitled Life and Progress in Australasia (1896). However, it is possible that Michael Davitt was made Patrick O’Leary’s godfather in 1895, rather than in 1888, the year of Patrick’s birth.

See: 1) “Michael Davitt interviewed”, The Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW), 12 July 1884, p. 7 (Davitt talks of “My projected lecture tour in Australia”)

2) “Rome: Michael Davitt visits the Catacombs before sailing for Australia”, The Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW), 16 May 1885, p. 7

3) “Davitt and his Australian trip”, The Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW), 6 June 1885, p. 9

4) “Michael Davitt will probably visit Australia”, Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 25 July 1885, p. 4 (“it is expected that he will come direct to Australia about August or September”)

5) “Michael Davitt”, Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners’ Advocate (Newcastle, NSW), 13 August 1885, p. 5 (“Michael Davitt has abandoned his projected lecturing tour through Australia”)

6) “Michael Davitt in Australia”, New Zealand Tablet (Dunedin, NZ), 7 June 1895, p. 15

See also: “Michael Davitt”, Wikipedia

bluey = a blanket; also may refer to a swagman’s bundle (a “swag”, being a number of items rolled up in a blanket, such blankets often being blue in colour)

Bohemian = someone who is socially unconventional in appearance and/or behaviour, who lives in an informal manner, especially someone who is involved in the arts (authors, musicians, painters, poets, etc.); an artistic type who does not conform to society’s norms; can also refer to a citizen or resident of Bohemia; (archaic) a Gypsy or Romani; of or relating to a Bohemian, a group or class of Bohemians, or the Bohemian lifestyle

Conrad = Joseph Conrad (1857-1924), born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, a Ukrainian-Polish-British author (born in Berdychiv, Ukraine, into a Polish family; died in England), especially known for his novels The Nigger of the Narcissus (1897), Heart of Darkness (1899), and Lord Jim (1900)

gloam = a shortened form of “gloaming”: dusk, twilight

hic jacet = (Latin, meaning “here lies”) the phrase “here lies”, often used as the beginning of an epitaph, especially as inscribed on a gravestone, usually (but not always) preceding the name of the deceased (e.g. “Here Lies the Body of M. Jane Wilcocks”; for John Keats, “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water”); an epitaph

See: 1) “Joseph Wilcocks: Dean and Priest/Minister”, Westminster Abbey

2) “File:John Keats Tombstone in Rome 01.jpg”, Wikipedia

morn = morning

Old Shake = William Shakespeare (1564-1616), English playwright and poet

par = an abbreviation of “paragraph” (may also refer to a level or standard, from the Latin “par” meaning “equal” or “equality”)

Providence = (usually capitalized) God, or benevolent care from God; care, guidance, or protection as provided by God, or as provided by coincidental circumstances or Nature

rouseabout = an unskilled worker, someone employed to carry out odd jobs or unskilled tasks, especially used regarding someone working in a shearing shed

Stevenson = Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson, a Scottish author and poet

sundowner = a swagman, or tramp, who walked from station to station, ostensibly to look for work, but with no intention of doing any, who would deliberately time his arrival at a farm or station late enough in the evening, or at sundown, so that he could ask for food and lodging, but with little to no risk of being asked to perform some work in exchange; can also refer to a swagman (in general terms, without the negative connotations regarding one who avoids work)

wain = a wagon or cart, pulled by horses or oxen, especially one used for farm work, usually a large heavy vehicle

[Editor: The original text has been separated into paragraphs.]

Leave a Reply