[Editor: This interview with Louisa Lawson (prefaced with some introductory remarks) was published in “The Red Page” section of The Bulletin (Sydney, NSW), 24 October 1896.]

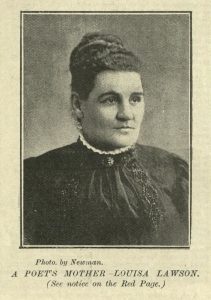

A poet’s mother — Louisa Lawson.

A poet’s mother — Louisa Lawson.

(See notice on the Red Page.)

“Something about myself? Oh, dear! Won’t it look very conceited? Well, if it does don’t blame me. Are you sure The Bulletin wants it? Do you know, I’d much rather not.

“I’m 48. But you don’t want to tell the people my age, do you? I was married when I was 18 — and what I’ve gone through since then! It would fill a book. You know my husband’s name was Peter Larsen, but Henry’s name is really Lawson — he was registered Lawson — that was the way people always spoke of my husband.

“He is dead years now. Of the children, I think Bert takes after him more; Henry is like me; Gertie is more like my mother. You have heard how clever Bert is at music? and everybody knows Henry. Gertie is with me now, working on The Dawn. Henry and Bert are in Westralia.

“My father is alive still — such a fine old man! — he must be about 75 now; mother died only the other day. Father’s father and mother were such good old people — that’s my grandfather and mother — Henry’s great-grand-parents. The old lady — she had worked hard all her life, poor soul! — she could reap her three-quarters of an acre of wheat in a day — and when she felt herself going to die she got out of bed and washed herself, dressed in clean clothes, lay down again, and folded her hands on her breast — ‘so as not to give trouble,’ she said.

“Father is a born poet; they tell me I take after him. You can see the likeness in this portrait; Henry is the same. He is a good old Kentish yeoman, is father; a big, strong, handsome man. You think I’m handsome? Do you really? I suppose I am tidier and stronger than most women; I’d need to be, for what I’ve gone through.

“And why shouldn’t a woman be tall and strong? I feel sorry for some of the women that come to see me sometimes; they look so weak and helpless — as if they expected me to pick ’em up and pull ’em to pieces and put ’em together again. I try to speak softly to them, but sometimes I can’t help letting out, and then they go away and say, ‘Mrs. Lawson was so unkind to us!’

“And whose fault is it but men’s? Women are what men make them. Why, a woman can’t bear a child without it being received into the hands of a male doctor; it is baptised by a fat old male parson; a girl goes through life obeying laws made by men; and if she breaks them, a male magistrate sends her to a gaol where a male warder handles her and looks in her cell at night to see she’s all right. If she gets so far as to be hanged, a male hangman puts the rope round her neck; she is buried by a male gravedigger; and she goes to a Heaven ruled over by a male God or a hell managed by a male devil. Isn’t it a wonder men didn’t make the devil a woman?

“Run down the men! Don’t you go away with that idea. Men are gods — and women are angels. And do you know what you make them suffer? I declare, it’s the most pitiful thing in the world. When I come sometimes to a meeting of these poor working women — little, dowdy, shabby things all worn down with care and babies — doing their best to bring up a family on the pittance they get from their husbands — and keep those husbands at home and away from the public-house — when I see their poor lined faces I feel inclined to cry. They suffer so much.

“And listen to their talk! so quiet and sensible. If you want real practical wisdom, go to an old washerwoman patching clothes on the Rocks with a black eye, and you’ll hear more true philosophy than a Parliament of men will talk in a twelve-month.

“No, I don’t run down men, but I run down their vanity — especially when they’re talking and writing about women. A man editing a ladies’ paper! or talking about a woman’s question in Parliament! I don’t know whether to laugh or cry; they know so little about us. We see it. Oh, why don’t the women laugh right out — not quietly to themselves; laugh all together; get up on the housetops and laugh, and startle you out of your self-satisfaction.

“Men are so self-satisfied. Why, would you believe it! I was talking a while ago to a member of Parliament and sympathising with him about his wife — he’s separated from her, poor thing! — and saying how hard people were on a woman that’s alone, and he looked up at me so innocently and said, ‘I’m not in the market, Mrs. Lawson.’ The fool thought I wanted to marry him! and to this day I believe he thinks he had a narrow escape. Poor men!

“Did you ever think what it was to be a woman, and have to try to make a living by herself, with so many men’s hands against her. It’s all right if she puts herself under the thumb of a man — she’s respectable then; but woe betide her if she strikes out for herself and tries to compete with men on what they call ‘their own ground.’ Who made it their own ground?

“Why, when I started out ten years ago to make a woman’s paper — The Dawn — this is the last number of it — the compositors boycotted me, and they even tried to boycott us at the Post Office — wouldn’t let it go through the post as a newspaper. I knew nothing about printing, but I felt I could write — or, anyhow, I felt I could feel — so I scraped a few pounds together and got a machine and some type, and I and the girls began to print without knowing any more about it than Adam.

“How did we learn to set type and lock up a forme? Goodness knows! Just worked at it till we puzzled it out! And how the men used to come and patronise us, and try to get something out of us! I remember one day a man from the Christian World came round to borrow a block — a picture. I wouldn’t lend it to him; I said we had paid a pound for it, and I couldn’t afford to go and buy blocks for other papers. Then he stood by the stone and sneered at the girls locking up the formes. We were just going to press, and you know locking-up isn’t always an easy matter — particularly for new-chums like we were.

“Well, he stood there and said nasty things, and poor Miss Greig — she’s my forewoman — and the girls, they got as white as chalk; the tears were in their eyes. I asked him three times to go, and he wouldn’t, so I took up a watering-pot full of water that we had for sweeping the floor, and I let him have it.

“It went up with a s-swish, and you should just have seen him! He was so nicely dressed — all white flannel and straw-hat, and spring flowers in his button-hole; and it wet him through — knocked his hat off and filled his coat-pocket full of water. He was brave, I’ll say that; he wouldn’t go; he just wiped himself and stood there getting nastier and nastier, and I lost patience. ‘Look here,’ I said, ‘do you know what we do in the bush to tramps that come bothering us? We give ’em clean water first, and then, if they won’t go, we give ’em something like this.’ And I took up the lye-bucket, that we used for cleaning type; it was thick, with an inch of black scum on it like jelly, that wobbled when you shook it. I held it under his nose, and said: ‘Do you see this?’ And he went in a hurry.

“Did Henry help me? He did that. His father thought a lot of Henry; he used to call him a tiger for work. Poor boy! when we were starting Dawn he used to turn the machine for us; he would just get some verse in his head and go on turning mechanically, forgetting all about us. He didn’t like to be interrupted when he was thinking, so often when the issue was all printed off we would go upstairs to supper and leave him there turning away at the empty machine, with his eyes shining.

“Are you married? I am glad; a bachelor is only half a man. But so many of you think that a wife is bought by a wedding-dress and a ring. No! a woman is bound to a man only by her love for him, her respect for him, to the extent of her trust and faith in him. O, if men would permit us to trust and honor them! We do so wish to.”

Source:

The Bulletin (Sydney, NSW), 24 October 1896, The Red Page, columns 1-2

Editor’s notes:

The photograph of Louisa Lawson appeared on page 10 of the same issue of The Bulletin.

’em = (vernacular) a contraction of “them”

Kendall = Henry Kendall (1839-1882), poet; he was born in Ulladulla (NSW) in 1839, and died in Surry Hills (NSW) in 1882

See: 1) T. T. Reed, “Kendall, Thomas Henry (1839–1882)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography

2) “Henry Kendall (poet)”, Wikipedia

new-chum = someone who is new at a job or a task; a learner (can also refer to: a newly-arrived immigrant, especially a British immigrant)

N.S.W. = an abbreviation of New South Wales (a colony in Australia from 1788, then a state in 1901)

photo. = (abbreviation) photograph

pound = a unit of British-style currency used in Australia, until it was replaced by the dollar in 1966 when decimal currency was introduced in Australia

public-house = hotel; an establishment where the main line of business is to sell alcoholic drinks for customers to consume on the premises (also known as a “pub”)

queer = odd, strange (can also refer to: feeling or being ill or unwell; a homosexual)

Red Page = the literature section of The Bulletin (Sydney, NSW), which included literary reviews, poems, and items regarding literature and writers (it was named the “Red Page” as it was published on the inside of the publication’s cover, which was printed on paper of a reddish colour)

the Rocks = an area of inner Sydney (New South Wales)

See: “The Rocks, New South Wales”, Wikipedia

twelve-month = a year (also spelt: twelvemonth)

Westralia = Western Australia (a contraction used to denote the state of Western Australia)

[Editor: Changed “expecially” to “especially”.]

Leave a Reply