The expedition of nineteen men departed from Royal Park, Melbourne, on 20 August 1860, led by Robert O’Hara Burke. They stopped at Swan Hill to take on supplies; whilst there Burke fired some of the men, and hired replacements. The party then went on to Menindee.

Problems had plagued Burke’s expedition, resulting in the resignations of George James Landells (who, up until then, was the party’s second-in-command) and Hermann Beckler (the expedition’s doctor), as well as the firing of thirteen of the men. Landells resigned his position at Menindee on 16 October 1860, following a disagreement with Burke.

News had come through that John Stuart, the explorer, was intending to cross the continent from south to north, with an expedition funded by the South Australian government, and Burke wanted to make sure that it was his party that traversed the length of Australia first.

Frustrated by the slow progress of the group, Burke split the party in two. William Wright was placed in charge of the expedition’s supplies at Menindee, and was given instructions to source further supplies and to bring them up to Cooper’s Creek. William John Wills became Burke’s lieutenant, to replace Landells as second-in-command. The personnel changes were made, and the expedition continued on, leaving Menindee on 19 October, with the others instructed to meet them at Cooper’s Creek.

Burke established a base at Cooper’s Creek (Camp 65) on 11 November. Whilst he was waiting for the remainder of the expedition to catch up with him, Burke decided to split the party again, and on 16 December he continued on towards the Gulf of Carpentaria, along with William Wills, John King, and Charles Gray. William Brahe was left in charge of the Cooper’s Creek base camp.

When they arrived at Little Bynoe River (part of the Flinders River delta) on 11 February 1861, Burke’s small party set up Camp 119. Most of the animals were so fatigued by their long-distance travelling that Burke decided to yet again split his group. He pressed on with Wills, leaving Gray and King with most of the animals.

Burke and Wills made it to the mangrove swamps of the Gulf of Carpentaria. Unfortunately, it would have taken far too long for them to work their way through the tangled swampland, especially given their physical condition and lack of food. Although Burke and Wills didn’t actually get to see the sea, they noted that the water was salty and that the tide was “flowing, rising and falling to the extent of eight inches”; therefore, as far as they were concerned, they had basically reached the top of Australia. As Burke was to later write in his journal, “it would be well to say that we reached the sea, but we could not obtain a view of the open ocean, although we made every endeavour to do so”.

The two men then returned to Camp 119, reuniting with Gray and King. On 12 February the four men began the arduous return journey to Cooper’s Creek.

During the long trek southward, Burke’s party began to run low on food, and they had to kill some of their animals for food. They also supplemented their food supplies with wild animals. Gray became ill, and had to be helped along, until he died from dysentery on 17 April.

In the meantime, the men at Cooper’s Creek had been waiting there for months, and were also beginning to run short of food. To make matters worse, they had some problems with the local Aborigines, who were stealing their supplies. Brahe warned off the Aborigines by firing his gun in the air, to reinforce his point, and the Aborigines left; however, they later came back, wearing war paint and armed with spears. With armed and angry Aborigines in the area, the men became wary about going out to kill animals for food, due to fears of being murdered by the blacks, which added to their food shortage problems.

Brahe faced a difficult decision. With the return of Burke’s party looking less and less likely (it was reasonable to suspect that they had died out in the wild), and needing to seek medical care for a injured man (William Patten) and counter the emergence of scurvy that was showing in the men, Brahe had to choose between waiting even longer for Burke (and risk his men dying), or returning to civilisation. Although Burke had instructed him to wait thirteen weeks for his return, Brahe had waited eighteen weeks and there was no still sign of them, so he decided that they should head back to Menindee.

Just in case the exploring party returned, Brahe left behind some supplies, which he buried (to avoid being eaten by wild animals or being damaged by the sun) in a box at the foot of a coolibah tree, upon the trunk of which he carved, in big letters, the instruction “Dig 3 ft. NW”, along with the day’s date. The group left the creek on the morning of 21 April 1861. As it turned out, the injured man, Patten, who was in poor health, died on 6 June.

In one of the biggest tragedies of Australian exploration, Burke’s party made it back to Cooper’s Creek in the evening of 21 April, approximately nine hours after Brahe had left; unfortunately, they were just too exhausted to dash after Brahe to catch up. After a day of recuperation, Burke struck out for Mount Hopeless on 23 April, following the creek, deeming it the easiest way to reach a European settlement. He left a note buried below the Dig Tree, but didn’t think to change the message or the date carved into the tree (by that time the small group had been suffering heat, exhaustion, and lack of food for some months, so it is probably of little surprise that they weren’t operating at their best).

Brahe, accompanied by Wright, arrived at the Cooper’s Creek camp on 8 May; however, they didn’t notice any signs that Burke had been there. They returned to Menindee.

Wills, at Burke’s request, went back to Cooper’s Creek, reaching the camp on 27 May. He left a note and buried his journals, then he retraced his steps and caught up with Burke and King on 3 June.

The luckless trio travelled towards South Australia, but became weaker day by day. Eventually Wills became too weak to go on, and told the others to leave him. The other two continued their trek, but Burke died three days later. When King returned to the waterhole where they had left Wills, he found that he was dead too.

King’s run of bad luck broke when he met with some friendly Aborigines of the Yantruwanta tribe, who took him in. About three and a half months later, on 15 September 1861, a rescue party (led by Alfred Howitt) found King, and he was therefore able to return to Melbourne, although his health had been permanently damaged as a consequence of the hardships suffered during the expedition.

Whilst the Burke and Wills expedition turned out to be a tragedy, it was also very useful for the information about the north of Australia that was uncovered — by the original group, as well by the rescue parties which went out to find them.

Much deserved criticism has been made of Burke’s leadership; however, he is mostly remembered for his bravery and determination in his task to find a route to the north of Australia and explore the interior of the continent.

It was due to the bravery of men like Burke and Wills that the exploration of the country was carried out, which therefore enabled the creation of modern Australia.

See also: The Burke and Wills expedition

A list of articles about the Burke and Wills expedition.

Note: This article was originally part of the above list, as an introductory essay; however, due to the length of the list and essay combined, it was decided to separate them into two separate posts.

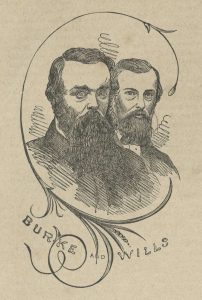

Image reference:

Burke and Wills, 1862, Melbourne: Charles Frederick Somerton, 1862 (wood engraving)

Leave a Reply