(Click here for a list of his works.)

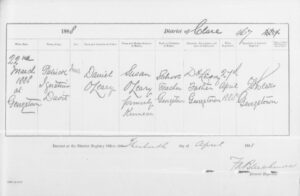

P. I. O’Leary was born in Georgetown, South Australia, on 22 March 1888. He was the fourth of nine children. His parents were Daniel James O’Leary (a school teacher, born in Ireland) and Susan O’Leary (née Kinnear).[2]

It would appear that his parent’s religious and political views played a part in their choice of Christian names for Patrick Ignatius Davitt O’Leary, if we can assume that “Patrick” was a reference to Saint Patrick of Ireland (a Catholic saint), “Ignatius” was from Saint Ignatius of Antioch (another Catholic saint), and “Davitt” was taken from Michael Davitt (the Irish Nationalist agitator and politician, who had planned to tour Australian in 1885, three years before Patrick’s birth, although the visit was postponed until 1895); in a 1944 article in The Advocate, James G. Murtagh claimed that Michael Davitt was Patrick’s godfather.[3]

His father encouraged Patrick to read. So the young lad, who was somewhat constrained by a limp, immersed himself in the world of literature; it was a world he was to excel in, and it became a large part of his life.[5]

After his father passed away in 1902 (he died at the school-residence at Crystal Brook, south-east of Port Pirrie), the family moved to Port Pirrie (on the east coast of the Spencer Gulf, SA), and then to Broken Hill (in New South Wales, just over the border from South Australia). Patrick worked as a rouseabout on sheep stations, and was a union organiser. He obtained his first job in journalism when he was hired onto the staff of The Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, NSW).[6]

James G. Murtagh, in The Advocate, described O’Leary’s early years in an idyllic fashion:

“The youth, Pat O’Leary, was caught up in the utopian idealism of the radicals and in the blunt Australian nationalism, with the “Bulletin” as its bible. But it was the romance and fellowship of the outback that first fired his poet’s soul. He learnt to know and love the bush, the freedom of the open road, the blazing Australian skies. He often took to the track and humped his “bluey” from Adelaide to Broken Hill, from the Hill all the way to Melbourne. He was at heart a sundowner, in tune with the great loneliness of the plains, the dusty roads and the little hot towns of the bush. He was a philosopher of mateship, one of the last of the tribe of Henry Lawson.”[7]

In 1912 Patrick Ignatius O’Leary married Mary Teresa Slattery at the Broken Hill Cathedral. The marriage was to produce four children: Mary Teresa (named after her mother), Margaret, Kevin (who became a Catholic priest), and Brian.[8]

The young couple moved to Adelaide (SA), where O’Leary worked as a journalist for The Advertiser. During the First World War (1914-1918), his newspaper employers campaigned in favour of a “Yes” vote for the referendum on conscription, but O’Leary publicly campaigned for the “No” vote, and did so in front of the newspaper’s offices no less. He was soon looking for another job.[9]

They then moved to Hummocky Hill (now known as Whyalla; on west coast of the Spencer Gulf, SA), and worked as a time-clerk for Broken Hill Pty. Ltd.[10]

At the end of the war, they moved to Melbourne, with Patrick hoping to gain employment in the literary world there; however, luck was not with him, and he ended up working on a stall at the Western market, selling polish for silverware.[11]

P. I. O’Leary sent articles and poems to various publications. Finally, his talent was recognised by the editor of the Catholic weekly newspaper, The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), who offered him a job in 1920. Patrick gladly joined the staff, and worked in a variety of roles, as a reporter, book-reviewer, literary critic, editorial writer, sub-editor, and editor; he was described as “a one-man magazine”. He wrote for The Advocate up until his death; it was from his articles in that publication that he gained his nationwide reputation. He had also contributed literary articles to several other publications, such as The Bulletin, The Lone Hand, The Southern Cross, Triad, and Youth.[12]

He became involved with the Australian literary scene, was active with the Bread and Cheese Club (a literary group, based in Melbourne), and was friends with several of the nation’s leading writers, including C. J. Dennis, “Furnley Maurice” (Frank Wilmot), Bernard O’Dowd, and Nettie and Vance Palmer.[13]

Being of Irish background, he found himself drawn to Irish causes, and thus became the national secretary of the Self-Determination for Ireland League of Australia. Indeed, The Advocate, as with the other Catholic publications in Australia at that time, maintained a stance in favour of Irish nationalism (a position no doubt brought about as a consequence of the large numbers of Irish priests and Irish Catholics within the Catholic church in Australia).[14]

Unfortunately, in 1944, his health deteriorated, and he was hospitalised. P. I. O’Leary died at the age of 56 in St. Vincent’s Hospital, Fitzroy (Melbourne, Vic.), on 21 July 1944.[15]

During his time in journalism, O’Leary had a significant impact upon the literary scene. In an article in The Advocate, about the Catholic media presence in Australia, it was said:

“Among Australian writers, first place, perhaps, should go to the late Patrick Ignatius O’Leary, for years the literary editor of the journal. It was he who discovered and attracted to its pages many a young writer and poet, and encouraged them in their early efforts.”[16]

Patrick Coady, in an article published in The Catholic Weekly, recognised the spark of genius in the writings of Patrick O’Leary, but acknowledged that the restrictive nature of meeting newspaper deadlines meant that his literary writing were not always as good as they might have been (the same has been written regarding others hemmed in by newspaper deadlines, such as Dryblower Murphy). Coady wrote:

“During the twenties in particular his literary criticism brought such prestige to the “Advocate” that it gained an international reputation. … he did not find ever the true heights of achievement, though he came very near.

… O’Leary had the talent, the peculiar genius, to have been a great writer, but I do not think he had the temperament. … he produces fine things, writing that is great writing, but they are isolated, magnificent flashes

… His critical articles — quickly-written magazine articles for the most part — show at their best a literary perception that few contemporary critics, Australian or otherwise, can approach, and at their worst, a misguided patriotism or a sentimental attitude where sharpness of view was needed.

… He would write of “a Henrifordian abandon” and then change his mood and produce sonorous, lovely prose. But often, the deadline would be against him and the style would be less polished, more verbally artful. If only he had had more time — or more concentration — what prose, in abundance, there would have been.”[17]

James G. Murtagh referred to O’Leary’s “literary genius” and his “intense Australianism”, and wrote eloquently about his burial:

“ His literary genius first found expression in short pars and verses, contributed to the “Bulletin”

… He never quite lost the social attitudes of his Broken Hill days. He idealised the code of mateship, that first flowering of Australian folkways, which grew up among the men of the bush in the eighties after the failure of the land struggles. Mateship was largely a class-conscious expression of frustrated social idealism. For P. I. O’L., with his poet’s insight, it was a surging of the spirit of fraternity among the exploited men without land. This side of O’Leary breathed an intense Australianism. It glowed like a fire — a camp fire — and his mates were Henry Lawson, Francis Adams, Roderic Quinn, Victor Daley, and the “Bulletin” poets of Australian nationalism.

… death waited quietly for the soul of Patrick Ignatius O’Leary. They buried him by the side of the road, out beyond the town, near a wattle tree, under three tall gums. There was a high wind rustling their leaves. And the sun. He would have asked no more. P. I. O’L. had found peace of body and soul.”[18]

With the death of O’Leary, Australia lost a fighter for the future of Australian literature, someone who was willing to use his talents in the furtherance of homegrown poetry and prose, and an able advocate for the Australian national identity.

Patrick Ignatius O’Leary did not write merely on behalf of himself, building up his own reputation in the literary world, but also strove to build up a wide recognition for the worth of Australian writings. As a literary critic and journalist, and as an encourager and promoter of Australian writers, he made a valuable contribution to the ongoing development of Australian literature.

Works by P. I. O’Leary:

Works of P. I. O’Leary

Articles about P. I. O’Leary:

Obituary: Mr P. I. O’Leary [obituary for P. I. O’Leary, 22 July 1944]

P.I.O’L. [obituary for P. I. O’Leary, 26 July 1944]

Journalist and Laborite dies [obituary for P. I. O’Leary, 27 July 1944]

The Open Road and the Inky Way: Patrick Ignatius O’Leary (1888-1944): Rover-poet and Catholic journalist [obituary for P. I. O’Leary, 2 August 1944]

On the track: A tribute to P.I.O’L. [obituary for P. I. O’Leary, 2 August 1944]

References:

[1] “O’Leary, P. I. (Patrick Ignatius) (1888-1944)”, Trove (National Library of Australia)

“Death of Mr. P. I. O’Leary: Catholic journalism sustains great loss”, The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 26 July 1944, p. 4 (re. “P.I.O’L.”)

James G. Murtagh, “The Open Road and the Inky Way: Patrick Ignatius O’Leary (1888-1944): Rover-poet and Catholic journalist”, The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 2 August 1944, pp. 9-10

“OLEARY, Patrick Ignatius Davit”, Genealogy SA (Patrick Ignatius Davit O’Leary, born 1888, father Daniel O’Leary, District: Clare, Book/Page: 414/467) [note: Patrick’s third Christian name is spelt, or misspelt, as “Davit”, i.e. with one T]

“OLEARY, Kathleen Patricia”, Genealogy SA (Kathleen Patricia O’Leary, born 1917, father Patrick Ignatius Davitt, District: Adelaide, Book/Page: 998/24) [note: the details for his daughter’s birth give Patrick’s third Christian name as “Davitt”, i.e. with two Ts]

[2] Birth record (22 March 1888), District Registry Office, District of Clare (SA), 13 April 1888, page 467

“Births, marriages, and deaths ”, The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA), 12 June 1902, p. 4 (death of Daniel James O’Leary)

“Births, marriages, and deaths”, The Southern Cross (Adelaide, SA), 23 April 1909, p. 264 (marriage of Minnie O’Leary, “second daughter of Susan O’Leary, of Broken Hill, and the late Daniel O’Leary, of Crystal Brook”)

James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

Patrick Coady, ““The story behind the initials — P.I.O’L.”: Bard in bondage”, The Catholic Weekly (Sydney, NSW), 30 September 1954, p. 12

[3] “St. Patrick: bishop and patron saint of Ireland ”, Encyclopædia Britannica

“St. Ignatius of Antioch: Syrian bishop”, Encyclopædia Britannica

James G. Murtagh, “The Open Road and the Inky Way: Patrick Ignatius O’Leary (1888-1944): Rover-poet and Catholic journalist, The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 2 August 1944, p. 9

This article stated that “The Irish patriot and reformer, Michael Davitt, who was visiting Australia, was god-father at his baptism.” It should be noted that whilst Michael Davitt had intended to tour Australia in 1885, his tour of Australia and New Zealand did not occur until 1895, following which he wrote a book about his experiences, observations, and opinions, entitled Life and Progress in Australasia (1896). However, it is possible that Michael Davitt was made Patrick O’Leary’s godfather in 1895, rather than in 1888, the year of Patrick’s birth.

See: a) “Michael Davitt interviewed”, The Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW), 12 July 1884, p. 7 (Davitt talks of “My projected lecture tour in Australia”)

b) “Rome: Michael Davitt visits the Catacombs before sailing for Australia”, The Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW), 16 May 1885, p. 7

c) “Davitt and his Australian trip”, The Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW), 6 June 1885, p. 9

d) “Michael Davitt will probably visit Australia”, Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 25 July 1885, p. 4 (“it is expected that he will come direct to Australia about August or September”)

e) “Michael Davitt”, Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners’ Advocate (Newcastle, NSW), 13 August 1885, p. 5 (“Michael Davitt has abandoned his projected lecturing tour through Australia”)

f) “Michael Davitt in Australia”, New Zealand Tablet (Dunedin, NZ), 7 June 1895, p. 15

See also:

“Saint Patrick”, Wikipedia

“Ignatius of Antioch”, Wikipedia

“Michael Davitt”, Wikipedia

[4] James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

Patrick Coady, 30 September 1954, op. cit.

[5] James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

Patrick Coady, 30 September 1954, op. cit.

[6] “Births, marriages, and deaths ”, The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA), 12 June 1902, p. 4 (death of Daniel James O’Leary)

“OLEARY, Daniel James”, Genealogy SA (Daniel James O’Leary, died 1902, District: Clare, Book/Page: 285/344)

“Journalist and Laborite dies”, The Labor Call (Melbourne, Vic.), 27 July 1944, p. 2

“Obituary”, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.), 22 July 1944, p. 3

“On the track: A tribute to P.I.O’L.”, The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 2 August 1944, p. 10

James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

Patrick Coady, 30 September 1954, op. cit.

[7] James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

[8] Births, Deaths and Marriages search, NSW Government (Patrick I. O’Leary and Mary T. Slattery; District: Broken Hill; Registration Number: 5251/1912)

“OLEARY, Kathleen Patricia”, Genealogy SA (Kathleen Patricia O’Leary, born: 1917, father: Patrick Ignatius Davitt, District: Adelaide, Book/Page: 998/24)

“Search your family history”, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Victoria

(birth record: OLEARY, Mary Teresa, reg. year 1918, reg. no. 19353/1918; father Patk Ignatius OLEARY)

“Births, marriages, deaths”, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.), 22 July 1944, p. 10 (column 3, in the “Deaths” section; death of Patrick Ignatius O’Leary, names his wife and children)

James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

Patrick Coady, 30 September 1954, op. cit.

““P.I.O’L’s” son ordained in Italy”, The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 5 July 1951, p. 2 (Rev. Kevin P. O’Leary)

[9] James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

Patrick Coady, 30 September 1954, op. cit.

[10] “Mr. Osborne’s memories”, The Recorder (Port Pirie, SA), 17 July 1950, p. 3 (“Hummocky Hill, later officially described as Whyalla”)

Patrick Coady, 30 September 1954, op. cit.

[11] Patrick Coady, 30 September 1954, op. cit.

[12] James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

Patrick Coady, 30 September 1954, op. cit.

[13] James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

[14] “Message To De Valera: To the editor of the Argus”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 26 August 1921, p. 7

“Self-determination and the Australian democracy”, The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 1 September 1921, p. 23

[15] “Births, marriages, deaths”, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.), 22 July 1944, p. 10 (column 3)

“Deaths”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 22 July 1944, p. 16 (column 2)

“Ex.-S.A. journalist dies in Melbourne”, The News (Adelaide, SA), 22 July 1944, p. 3

“Births, marriages, deaths”, The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA), 25 July 1944, p. 8 (column 2; notice inserted by his siblings)

“Births, marriages and deaths”, The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 18 July 1945, p. 21 (in the “In memoriam” section)

[16] “The Catholic press and radio in Melbourne”, The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.), 13 May 1948, p. 37

[17] Patrick Coady, 30 September 1954, op. cit.

[18] James G. Murtagh, 2 August 1944, op. cit.

Updated 14 August 2023

Leave a Reply