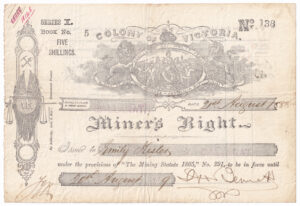

Unlike the Gold License, the early Miner’s Right, in addition to the right to prospect for gold, also carried with it certain other advantages, such as property rights and voting rights.

The Miner’s Right came about as a recommendation of a government-appointed commission, which had been appointed on 1854 to look into the troubles on the Victorian goldfields, especially regarding the Eureka Rebellion.

The discovery of gold

Although some small amounts of gold had been found in New South Wales prior to the 1850s, the discoveries had been kept quiet so as to not disrupt the workings of the colony by the creation of “gold fever” or a “gold rush”. But then, in May 1851, with the publicly-acclaimed discovery of gold in New South Wales, came a popular rush for riches on the goldfields.

Then gold was discovered in Victoria in August 1851, with goldfields established at Anderson’s Creek (now Warrandyte) and Clunes, and subsequently at other places, such as Ballarat, Bendigo, Creswick, Mount Alexander, and the Ovens River district.[1]

This meant that the colonial government of Victoria faced some new and major challenges. People left their jobs in droves, to go and seek their fortunes on the goldfields. It would have been a hard time for any administration to cope with such changes; however, the Colony of Victoria had only just separated from the Colony of New South Wales (on 1 July 1851), so the advent of the gold rushes in Victoria was a hectic time for a relatively untested government.[2]

Widespread concerns about the loss of workers in the cities and in the farming sector were reflected in a report written by the Geelong correspondent for The Argus:

“We have got abundance of gold, and the evil effects of the discovery are following fast in the wake of it. Already wages are rising, the common necessaries of life are rising, wood and water are rising. There is no appearance of the demand for labour for our shearing and harvest being supplied

… The women and children may remain in town, but the male adults will go to the mines.

… The evil is of such magnitude and the position of the colony with its government so unsettled, that I would strongly advise the immediate appointment, by public meeting, of a deputation to meet the Executive and consider the best means of averting what is likely to become a great public calamity.

Geelong, and I suppose Melbourne is similarly situated, is being depopulated. The police force are handing in resignations daily; even the sergeants are leaving. The Custom House hands are off to the diggings, seamen are deserting their vessels; tradesmen and apprentices are gone, their masters are following them; contractors men have bolted, and left large expensive jobs on their hands unfinished.

… Many suggestions have been thrown out as to the best remedy for the disease, which is fast taking root and which, if not checked in time, may carry us off. Some have hinted that the license ought to be doubled and trebled; others, and the Advertiser of this morning is among the number, suggest that the licenses be suspended entirely for a given period; a third party are of opinion that all the prisoners here, and as many as can be borrowed from Van Diemen’s Land, should be employed by the Government in the harvest season, to secure the crops; but all these suggestions are either extremely dangerous to adopt, or impossible to carry out.

… Our labour market has been drained, and our social habits for a time almost revolutionized by the extraordinary rush to the gold field. The possession of gold is the cause. The stoppage of the ordinary branches of industry, and a rise in the necessaries of life are the effects.”[3]

The depopulation of cities, towns, and rural areas, by people heading off to the goldfields to seek their fortunes, was a major issue for the Victorian government. Ships, shops, factories, farms, and a host of other essential services, were all affected by the loss of staff. Perhaps the problem could have sorted itself out in the end, with the usual trials and tribulations of the fine balancing act of supply and demand between goods, services, prices, and workers, but the situation could have thrown the Colony of Victoria into a state of chaos in the meantime, so the government decided to act.

The introduction of the Gold License

The Victorian administration dealt with the situation by introducing a Gold License (as notified in the government gazette of 16 August 1851), with the new regulations coming into force on 1 September 1851, although the licenses were not issued at Ballaarat until 20 September 1851. The price of a Gold License was set at 30 shillings per month, which was a substantial sum in those days. The purchase of the license would cost more than two or three weeks’ wages for many people; for example, the usual weekly wage paid to hut-keepers was about 8 to 8.5 shillings; shepherds, about 8.5 to 9 shillings; bullock drivers, 14 shillings; and cooks, 12 to 14 shillings. Since the license was only valid for a month, that meant that any ordinary worker who was not lucky enough to find enough gold to cover at least the cost of their license, as well as their living costs, either had to give up looking for gold, or to continue on illegally.[4]

Of course, it was always possible that the miners could sell their meagre possessions in order to raise the cash, dip into their savings (if they had any), or borrow money (if they had a wealthy enough friend who was willing to risk it). For many, the choice was obvious — go on looking for gold, and hope to avoid the clutches of the law.

In August 1851, the Victorian government proposed to raise the monthly fee to £3 per month (i.e. 60 shillings). As this would have doubled the existing fee, which was already regarded as being far too much, there were many protestations against the proposal. In the face of such strong opposition, the government backed down, and did not increase the fee. However, the cost of the Gold License was still too high for many.[5]

The Gold License fee was deliberately set at a high rate, to discourage people from going to the goldfields, as well as to prompt others to leave the diggings when it became too financially hard for them to renew their licenses. When the gold rush in Victoria began, many people left their ordinary occupations to go off to find that rare yellow metal, and to become rich; however, this exodus from civilisation affected the flow of ordinary commerce, needed to maintain a modern lifestyle. This meant that the workings of life in the city and country were substantially affected, which was something the government was keen to change — and having a steep Gold License fee was a tactic which could force diggers back to their normal occupations.[6]

Lieutenant-Governor Charles Joseph La Trobe outlined three reasons behind the proposed doubling of the Gold License fee, which were 1) the license system was bringing in very little money, compared to the public costs associated with gold mining, 2) the Legislative Council refused to release funds from the public revenue to cover government expenses regarding the goldfields and the diggers who were hunting for gold (such as postal services, roads, a wider police presence, etc.), and 3) to force people back to their usual occupations. In a communiqué addressed to Earl Grey (dated 3 December 1851), La Trobe wrote that his third reason behind the proposed fee increase was:

“To place some additional impediments in the way of those frequenting the gold fields, who may not be in a position, or of a character, to prosecute the search with advantage to themselves or the community.”[7]

Gold Licenses and “digger hunting”

Diggers were fined £5 if they were found without a Gold License on them. This meant that they had to carry their license at all times — but to do so was not practical when one was working in wet and muddy conditions, as the thin paper license could easily become damaged, even to the extent of the text upon it becoming unrecognizable (in which case, it was useless). Even if a miner had his license in his tent a short distance away, he might not be allowed to retrieve his license, and could therefore be arrested — indeed, considering that the police received a cut of the fines, it was in the interest of any corrupt policeman to not allow a miner to go elsewhere to get his license, as the officer of the law would then miss out on his ill-gotten gains from the fines system. Intending miners who had just arrived at the diggings, and who had not had the opportunity to buy a license, could be arrested by the police for not possessing the necessary document, and would have to pay a £5 fine. Considering that £5 was the equivalent of two month’s pay for some people (e.g. farm workers), it is understandable why anger and frustration was riding high on the goldfields.[8]

Of major concern was the policy under which the police were given half of the fines issued; this practice obviously encouraged any and all corrupt policemen to issue as many fines as they could, even when they were inappropriate. Many of the regular police force had left their jobs to go to the goldfields (for example, at one police muster, 49 out of 55 police officers resigned). Therefore the government, in desperation, lowered their standards, and began recruiting ex-convicts, many of whom came from Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), and who were often little more than hired thugs wearing a police uniform.[9]

John Foster, who had been the Chief Secretary of Victoria, referred to the Victorian police of 1852 in the following terms: “convicts, drunkards, open to bribery and wholly untrustworthy”.[10]

R. M. McGowan, State Archivist of Victoria (in 1950), has explained the problem as follows:

“To the injustice of the licence, then, was then added injury, in the objectionable, arrogant, and insulting manner in which the Vandemonians conducted the “licence hunts.””[11]

The police conducted license inspections (known to the miners as “digger hunts”) to find any gold-seekers who had not taken out the requisite license. The conduct of the police was quite brutal. Offenders could be chained to a log or a tree, whilst the police went off to hunt for more wayward diggers. La Trobe reported that all of those who had been chained up, as a result of a license inspection, had also been charged with other offences. La Trobe may have meant his report to indicate that the chained men were troublemakers; however, an alternative possibility is that the miners were being “loaded up” with extra charges by corrupt policemen, who were looking to increase their income with payments from other fines.[12]

A petition from miners, presented to the Legislative Council, complained about the treatment of the gold-seekers by the Goldfields Commissioners (and the police who enforced their orders):

“That your Petitioners look with abhorrence on the principle carried out by the Commissioners on the Gold Fields, of chaining men to logs and trees like felons, because these men are not able to pay their license money.”[13]

Robert Ross Haverfield, a journalist and newspaper editor, quoted in The Bendigo Advertiser in 1888, described some of the problems which faced gold diggers in the early 1850s:

“Digger hunting, as the search after men who had no licenses was called, was a favorite amusement of both officers and men; and it was followed up savagely, relentlessly and with a refinement of cold-blooded cruelty, that were not only exasperating, but disgusting in the extreme. Men were chained to trees and logs throughout the blazing heat of day, or the piercing cold of night, whose offences consisted simply in not being able to produce their licenses on demand; although they protested and their statements were often found to be correct, that they had left these precious documents accidentally at home. But unless they had them in their pockets they were placed under arrest. It is true that many of them had neglected to take out licenses. But some of them pleaded poverty, or represented the impossibility of leaving their claims sufficiently long to enable them to visit the camp. It did’nt matter; they were all subjected alike to the indignity of being treated as criminals. Little wonder was it that disaffection was engendered to a dangerous degree.”[14]

In response to the terrible behaviour of the authorities, a type of camaraderie developed on the goldfields between the miners, with the diggers being united in their mutual hatred of the arrogant, bullying, and corrupt police. Whenever the police began their rounds of the goldfields, the miners would shout out, to let each other know that the cops were coming. It was a common practice for miners, when the police were sighted, to begin calling out “Joe!” — this was a reference to head of the Victorian government, Charles Joseph La Trobe (who was referred to, somewhat disrespectfully, as “Charley Joe”). The term “Joe” gained wider currency, and was also used to refer policemen outside the confines of the goldfields.[15]

Large public meetings were held at several goldfields in Victoria to protest the cost of the mining licenses and the way in which the licensing system was enforced by the police. Miners’ protest meetings were held at various places, including Ballarat, Beechworth, Bendigo, Castlemaine, Creswick, Heathcote, Jones’ Creek, Sandhurst, and Waranga.[16]

La Trobe, Foster, and Hotham

When La Trobe became aware of the high level of disaffection amongst the diggers, and the possibility of rebellion, he communicated to the British authorities that having a Gold License was no longer the optimum way of raising revenue from gold mining, although finding an effective alternative was problematic. In a communiqué to the Duke of Newcastle (dated 12 September 1853) he wrote:

“the best authority at my command still pointed to the probability of reduction in the license fee, if not a total abandonment of it. … But the more the subject was considered under the light which the unmistakeable direction of public feeling now afforded, the more difficult it appeared to suggest any modification of the present system which would secure the advantages and be free from the objections which every one now acknowledged”[17]

The extraordinary high cost of the mining license was a major source of aggravation and anger amongst the mining population. Additionally, the arrogant, bullying, and overbearing manner of the police towards the miners, when they came to check for mining licenses, created a widespread feeling of ill-will amongst the miners towards the police and the government. The grievances of the gold diggers were especially prominent at Ballarat, where police officials issued orders from their compound (referred to as “the Camp”) for their troopers to harass the diggers relentlessly.[18]

The Colonial Secretary of Victoria, John Foster, had opposed the Gold License scheme as it was, in practice, an unpopular and oppressive measure; instead, he advocated for a gold export tax. His view was:

“The whole system of licence fees was so faulty that it was certain, sooner or later, to end in disturbance. The whole body of the miners were constantly arrayed against the Government by it, and it placed the police in a state of direct antagonism and unpopularity with the diggers. The evil was inherent in the system itself.”[19]

As Foster was the public face of the Victorian government, with his name appearing on government proclamations, he was blamed for the troubles on the goldfields; this was rather ironic, since he opposed the measures which had caused the problems. Indeed, in November 1853, both Foster and La Trobe had supported a bill to abolish the Gold License, but that proposed law had been rejected by the Legislative Council. This was in stark contrast to Hotham (La Trobe’s replacement) had come to the colony after being instructed to keep the Gold License system in place. Nonetheless, Foster eventually became the scapegoat for the troubles on the goldfields — following the battle of the Eureka Stockade on the 3rd of December 1854, he was pressured by Hotham to resign, and so Foster subsequently left his position shortly afterwards.[20]

Charles Hotham arrived in Melbourne in June 1854 to replace La Trobe. In August he visited the gold diggings; crowds of miners, thinking that Hotham was a “new broom” who would sweep away all of the petty tyranny which occurred during La Trobe’s reign, welcomed him with cheers. The miners misunderstood Hotham, and in turn he misunderstood them; he apparently thought that the demeanor of the cheering crowds indicated that all was well with life on the diggings. Instead of fixing the problems on the goldfields, he made the situation worse, by ordering twice-weekly license inspections (the “digger hunts”, so hated by the miners). As T. H. Irving wrote, “Hotham … encouraged the police and troops on the fields to crush resistance.”[21]

According to a report in The Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, on 4 December 1854, the fault of this disconnect, between citizens and government, lay with the government officials:

“The diggers, as a body, are now antagonistic to Government. This state of affairs has been precipitated by the ill-judged severity of the Camp officials — the diggers suffering under heavy grievances have been endeavouring by the legitimate means of petitioning and sending delegates to head quarters.

The authorities on the ground in the meantime have driven them to desperation in pushing the obnoxious license tax, enforcing it with such rigour and severity, as if their chief intention was to find out by experiment how much contumely and disgrace — how much slavery oppression a free people would endure before kicking against authority.

… that horde of worse than useless officials on our gold field … have by their despotic misrule gone far to alienate from Government a naturally peaceable and law-loving community, and instead of upholding the dignity and protection of the British law, they have laboured hard to bring about, in the diggers’ minds, a contempt and mistrust of everything and every one in authority.”[22]

Police murderers and government responsibility

The ongoing agitation on the Ballarat goldfields led to the Eureka Rebellion, which culminated in the battle at the Eureka Stockade, on the 3rd of December 1854, when police and military forces attacked the diggers’ stockade. After the battle was over, a number of the attackers then ran amok, stabbing and killing men who had surrendered, as well as some innocent bystanders.[23]

For example, Henry Powell, who heard the shooting of the Eureka battle, came out of his tent to see what was going on. He was met by a group of police troopers, who demanded that he surrender, which he did. By this time, about 20 to 30 policemen had gathered, at which point Powell made the jocular remark “Very well, gentlemen, don’t be in a hurry, there are plenty of you.” The unarmed Powell was then knocked down by one policeman, and then was shot and stabbed by several others, who then rode over his body with their horses. None of the other policemen present arrested the attackers. Powell lived for a short time after the horrendous attack, and gave a statement of the occurrence; he subsequently died from the wounds inflicted by the police.[24]

Unfortunately, Henry Powell was not the only victim of wanton police brutality on that day. The report on the deliberations of the jury appointed at the inquest to consider the killing of Powell stated:

“The jury view with extreme horror the brutal conduct of the mounted police, in firing at and cutting down unarmed and innocent persons of both sexes at a distance from the scene of disturbance on December 3rd, 1854.”[25]

A major reason for the rebellion against the government was the government itself. Had the Victorian administration not allowed its police minions to act in such an overbearing, arrogant, and heavy-handed manner, all of the troubles could have been avoided. By not implementing a closer watch over the activities of its own officials, the government had indirectly encouraged a rebellion by the oppressed miners.

Dr. Geoffrey Serle considered that Charles Hotham was largely to blame:

“Eureka could easily have been avoided, but Governor Hotham was determined to teach the diggers a lesson. He quite misunderstood their attitude; on the whole they were a law-abiding and respectable body of men who were being goaded beyond endurance by the petty tyranny of local officialdom.”[26]

The Goldfields Commission

As a result of all of the troubles on the goldfields, the Victorian government appointed a Commission to look into the problems. The government had already decided to appoint a Commission before the battle at Eureka had occurred, but the Eureka incident demonstrated the urgent necessity of such an investigation; however, the Commission was not officially appointed until 7 December 1854 (four days after the Battle of the Eureka Stockade). The Commission consisted of William Westgarth (Chairman), John Pascoe Fawkner, John Hodgson, John O’Shanassy, James Ford Strachan, and William Henry Wright (along with Charles Warburton Carr, Secretary to the Commission).[27]

When the Commission issued its report, one of its recommendations was the introduction of a Miner’s Right, with a nominal price (“a small charge”, costing far less than the Gold License); their report recommended “a charge of £1”, along with the Miner’s Right “enabling the miner to qualify for the franchise” (i.e. giving the owner the right to vote in elections). The Commission also recommended “a moderate export duty” to be charged on gold, as an alternative way of raising revenue.[28]

John O’Shanassy is credited with the idea of named the new mining license as a “Miner’s Right”. William Westgarth, in his Personal Recollections of Early Melbourne & Victoria (1888), wrote:

“I recollect and record with pleasure one of the Goldfields Commission incidents illustrative of O’Shanassy’s high public qualities. We had completed at Castlemaine, near the original Mount Alexander, our considerable tour of goldfields inspection; and as we sat round the table of the only public room of the small hotel or public-house of the place, the evidence completed, and all the proposed changes decided on, there remained yet one question. Our proposed chief pecuniary change abolished the indiscriminate, and, to the many unsuccessful, most oppressive charge of 30s. monthly license fee, and substituted a yearly fee or fine of only 20s. And what was this, or the documentary receipt that represented it, to be called? Reduced as the amount was, it was still a tax, and any ingenuity that could dignify or otherwise reconcile a tax, was worthy of the best statecraft. As chairman, and not having at the moment a suggestion of my own, I had to knock at the heads of my co-members. I turned to one, then another, and yet another, but without response. Even the original brain of Fawkner sent forth no sign. At length I came to O’Shanassy, who happened to be at the far end of the table. He had been waiting his turn, and the answer came promptly, “Call it the Miner’s Right.” It was but one out of many instances of his statesmanlike turn. The Miner’s Right, of course, it was called. The name passed on to many other goldfields.”[29]

In its report, the Commission said that the behaviour of the police in collecting the license fee was a major reason for the problems on the goldfields. The report stated:

“The license fee, or more properly the unseemly violence often necessary for its due collection — a result entirely unavoidable in thus taxing for this considerable rate every individual of a great mass of laboring population; involving as it did repeated conflicts with the police, an ill-will to the authorities, from their almost continuous “hunt” to detect unlicensed persons, and the constant infraction of the law on the part of the miners, resulting sometimes from accident in losing the license document, or from absolute inability to pay for it, as well as from any attempt to evade the charge.”[30]

After the passing of the Gold Fields Act 1855, which was assented to on 12 June 1855, the Miner’s Right was introduced in Victoria. Even though a notice, dated 16 July 1855, was published in the Victorian Government Gazette, announcing the availability of the Miners’ Rights, it took a while for these new documents to reach some areas.[31]

Following the recommendation of the Gold Fields’ Commission of Enquiry, the Victorian government established the Miner’s Right as the new type of gold license. The cost of a Miner’s Right was £1 per annum (i.e. 20 shillings per year); this was far less costly than the previous Gold License, which cost 30 shillings per month. As an alternate way of taxing the gold output, the government instituted a gold export duty (at 2s. 6d per ounce).[32]

Being in possession of a Miner’s Rights meant that its owner could search for gold, build a home on Crown land to live in, and chop down trees for use in the home or for the purposes of gold prospecting. The holders of Miners’ Rights were also entitled to vote for Local Courts, which were created to handle miners’ disputes and to make rulings on matters affecting the diggers.[33]

The “digger hunts” were stopped, and the miners were generally happy with the Miner’s Right and their new right to vote (although there were still some kinks to be worked out in the legislation).[34]

The other Australian colonies followed suit, and issued their own Miners’ Rights. The term was also used for mining licenses in New Zealand.[35]

Miners’ Rights in modern times

Miners’ Rights are still issued in modern times, although not in all states of Australia. They are still available in Victoria, which is historically significant, and culturally importantly, as that state was the creator of this historical license.

A Miner’s Right is far cheaper in modern times than when that document was first introduced. The cost of a Miner’s Right in Victoria in 1855, valid for one year, was £1, which was 3.3% of the annual income of many farm labourers (£30); whereas the cost of a Miner’s Right in 2023 is $27, which is only 0.03% of the Australian median annual salary of $79,800 — although, as the modern version is valid for ten years, the cost drops down to only $2.70 per year, or 0.003% of the median annual salary.[36]

Miners’ Rights continue to play a role in modern times, as they are still being issued to seekers of gold. This historical license gives us a link between old and new Australia, providing a piece of living culture, being a part of an ongoing historical connection, and a reminder of our progress from the social-political upheavals of the 19th century, with a large section of the population lacking the voting franchise, to the easier mode of living in modern-day Australia, with widespread voting rights.

References:

[1] Gold Fields’ Commission of Enquiry, Report of the Commission Appointed to Enquire into the Condition of the Gold Fields of Victoria, &c. &c.”, Melbourne (Vic.): John Ferres (Government Printer), 1855, p. viii, sections 4-5 (PDF p. 9) [Anderson’s Creek and Clunes]

“Andersons Creek, Warrandyte”, Doncaster Templestowe Historical Society [“Warrandyte was originally called Anderson’s Creek”]

[2] Gold Fields’ Commission of Enquiry, 1855, op. cit., p. viii, section 6 (PDF p. 9)

[3] “Geelong”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 3 October 1851, p. 2

[4] “Proclamation” (entry dated 16 August 1851), Victoria Government Gazette (supplement to no. 6 of Wednesday, August 13th 1851), 16 August 1851, p. [p. 209] [La Trobe’s declaration that all gold deposits belongs to the Crown; Licenses to be issued]

“Licenses to dig and search for gold” (dated 18 August 1851), Victoria Government Gazette, 27 August 1851, p. [p. 307] [regulations re Licenses to come into effect as of 1 September 1851]

Gold Fields’ Commission of Enquiry, 1855, op. cit., p. viii, section 6 (PDF p. 9) [“license fee or royalty of 30s. per month”; “the first licenses were issued at Ballaarat on 20th September”]

“Labour report, Geelong”, The Geelong Advertiser (North Geelong, Vic.), 6 January 1851, p. 2 [re weekly wages]

“Wages in Australia”, Institute of Australian Culture [re weekly wages]

[5] George Mackay, The History of Bendigo, Bendigo: MacKay & Co., 1891, p. 18

Bruce Kent, “Agitations on the Victorian gold fields, 1851-1854: An interpretation”, in: Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement (2nd edition), Carlton (Vic.): Melbourne University Press, 1965, pp. 3-4

[6] Alan Gross, Charles Joseph La Trobe: Superintendent of the Port Phillip District 1839-1851; Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria 1851-1854, Melbourne University Press, Carlton (Vic.), 1980, p. 115

[7] “Copy of a despatch from Lieutenant-Governor Latrobe to Earl Grey” (dated 3 December 1851), in Further Papers Relative to the Recent Discovery of Gold in Australia (PDF pp. 366-522), London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1852, pp. 51-52 (PDF pp. 428-429), in Accounts and Papers: Twenty-Nine Volumes: 7: Colonies: Australian Colonies; Emigration (Session: 3 February — 1 July 1852), vol. xxxiv

[8] “Gold diggers meeting”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 31 March 1852, pp. 4-5 (see p. 4, column 7) [intending miners “not given time to go to the Commissioner’s tent for a license”]

Suzanne Mellor (editor), Australian History: The Occupation of a Continent, Blackburn (Vic.): Eureka Publishing Co., 1978, p. 177 [£5 fine]

“Wages in Australia”, Institute of Australian Culture

[9] Suzanne Mellor, 1978, op. cit., p. 176 [half of fines]

Alan Gross, 1980, op. cit., pp. 114 [muster], 117 [half of fines]

[10] Alan Gross, 1980, op. cit., pp. 114

[11] R. M. McGowan, “Historic events at Ballaarat”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 24 June 1950, p. 12 of The Argus Week-End Magazine supplement

[12] Suzanne Mellor, 1978, op. cit., p. 177 [men chained]

Alan Gross, 1980, op. cit., pp. 114-115 [men chained; La Trobe report]

T. H. Irving, “1850-70”, in: F. K. Crowley (editor), A New History of Australia, Melbourne (Vic.): William Heinemann Melbourne, 1980, p. 141 [“digger hunts”]

[13] M. O’Farrell and Alexander Fyfe, “To the Honorable the Legislative Council of the Colony of Victoria, in Council Assembled” (petition), in: Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council on the Gold Fields, together with the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, and Appendix, Melbourne: John Ferres (government printer), 1853 [PDF pp. 482-], (see p. 112, Appendix D); in: Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Council During the Session 1853-54, With Copies of the Various Documents Ordered by the Council to be Printed, vol. III, Melbourne: John Ferres (government printer), 1854

[14] A Young Bendigonian, “Bendigo since ’51: No. II”, The Bendigo Advertiser (Sandhurst, Vic.), 6 October 1888, p. 3

See also: George Mackay, The History of Bendigo, Bendigo: MacKay & Co., 1891, pp. preface, 9

“Death of a veteran journalist”, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.), 22 April 1889, p. 5 [obituary for Robert Ross Haverfield]

[15] “Great meeting of diggers: Passive resistance to the license tax: Gold fields’ reform”, The Mount Alexander Mail (Castlemaine, Vic.), 8 December 1854, supplement p. 1 (“The Mount Alexander Mail Extraordinary”), column 6 [Mr. Denovan asks diggers not to use the term: “If the police went round on Monday, the people were to refrain from crying ‘Joe’ — that was disgraceful, and they had higher game to play.”]

“Balaarat”, The Mount Alexander Mail (Castlemaine, Vic.), 8 December 1854, supplement p. 1 (“The Mount Alexander Mail Extraordinary”) [“Alexander Frazer was fined 40s. for calling out ‘Joe’ to a sergeant of the mounted police”]

““Joeing” a trooper” (in the “Domestic intelligence” section), The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 9 January 1855, p. 5, column 6

“Domestic intelligence”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 31 January 1855, p. 5, column 6 [Melbourne: “Robert Thrutchly, for being drunk and calling out “Joe” to a policeman, was fined 20s.”]

A [an anonymous poet], “The Lament of the Screw-tator”, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.), 12 June 1855, p. 3 [this poet says that he was “served by a Joe” at a ball held in the Government House in Toorak]

Raffaello Carboni, The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting on Quarter-Deck a Rebellion, Adelaide (SA): Public Library of South Australia, 1962 (facsimile of the 1855 edition), chapter 59, pp. 75-76

“Eureka Stockade: Ballarat in Fifties: Central Queensland in Sixties: Mr. John Davis’ reminiscences”, The Central Queensland Herald (Rockhampton, Qld.), 15 October 1931, p. 55 [“the police were rounding up the diggers for their licenses and heard the miners calling out ‘Jo!’”]

Suzanne Mellor, 1978, op. cit., p. 177 [the cry ‘Joe Joe!’]

[16] “Bendigo”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 21 October 1854, p. 6

“Meeting of diggers”, The Mount Alexander Mail (Castlemaine, Vic.), 17 November 1854, p. 5 [re Castlemaine meeting]

“Ballaarat”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 1 December 1854, p. 5 [Ballarat meeting]

“Ballaarat”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 4 December 1854, p. 5 [mentions Creswick meeting]

“Copy of a despatch from Lieutenant-Governor Latrobe to the Duke of Newcastle” (dated 12 September 1853), in: Further Papers Relative to the Discovery of Gold in Australia, London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1854, pp. 158-167, (see p. 164), in: The Seasonal Papers of the House of Lords in the Session 1854: Vol. XIV: Accounts and Papers: Colonies: (Australian Colonies), [London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office], 1854 [mentions meetings at Ballarat, Beechworth, Heathcote, Jones’ Creek, Sandhurst, Waranga]

[17] “Copy of a despatch from Lieutenant-Governor Latrobe to the Duke of Newcastle” (dated 12 September 1853), op. cit., p. 163 (sections 15, 17)

[18] “Eureka: Symbol of man’s fighting spirit”, The Herald, (Melbourne, Vic.), 23 November 1946, p. 13 [“licensing was in the hands of officials of various degrees of competence and arrogance, and of a police force at the time often corrupt … and given to bullying and cursing at all and sundry”]

[19] Ian MacFarlane (editor), Eureka: From the Official Records (2nd printing), Melbourne (Vic.): Public Records Office, 1995, pp. 26-27

Geoffrey Serle, “The causes of Eureka”, in: Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement (2nd edition), Carlton (Vic.): Melbourne University Press, 1965, p. 43

[20] Betty Malone “Foster, John Leslie Fitzgerald Vesey (1818–1900)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University

Geoffrey Serle, “The causes of Eureka”, 1965, op. cit., p. 43

Ian MacFarlane, 1995, op. cit., pp. 26, 28

[21] T. H. Irving, 1980, op. cit., p. 141 [Hotham’s misunderstanding; twice-weekly digger hunts; “crush resistance”]

Ian MacFarlane, 1995, op. cit., pp. 8-9 [Hotham’s misunderstanding]

[22] William Paterson, “Gold circular”, The Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, (Geelong, Vic.), 4 December 1854, p. 4

[23] “Ballarat: The statement of Frank Arthur Hasleham”, The Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer (Geelong, Vic.), 28 December 1854, p. 2 [statement of Frank Arthur Hasleham, a newspaper correspondent and an unarmed bystander, who was shot by the police after the Battle of the Eureka Stockade had ended]

Raffaello Carboni, The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting on Quarter-Deck a Rebellion, Adelaide (SA): Public Library of South Australia, 1962 (facsimile of the 1855 edition), chapters 59, p. 74 [Carboni says he was shot at by a police trooper, after the battle had ended]

[24] “Ballaarat”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 15 December 1854, pp. 4-5 (see p. 5) [“Deposition of Henry Powell”]

[25] “Ballaarat”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 15 December 1854, pp. 4-5 (see p. 5)

[26] Geoffrey Serle, “Gold and Democracy”, ABC Weekly (Sydney, NSW), 16 June 1956, p. 8

Note: Alan Gross has made a similar comment: “Throughout the diggings the cry was always for the franchise; the goad was the petty tyranny of local officialdom.”

Alan Gross, Charles Joseph La Trobe, 1980, op. cit., p. 123

[27] Gold Fields’ Commission of Enquiry, 1855, op. cit., pp. v-vii (PDF pp. 7-8)

[28] Gold Fields’ Commission of Enquiry, 1855, op. cit., pp. xiii-xiv, section 23 (PDF p. 14-15) and p. 364, Appendix E (PDF p. 439)

[29] William Westgarth, Personal Recollections of Early Melbourne & Victoria, Melbourne: George Robertson & Company, 1888, pp. 82-83

[30] Gold Fields’ Commission of Enquiry, 1855, op. cit., p. xi (PDF p. 12)

[31] “An Act to amend the Laws relating to the Gold Fields”, Australasian Legal Information Institute [“Assented to 12th June, 1855”]

“Miners’ Rights” (entry dated 16 July 1855), Victoria Government Gazette, no. 68, 17 July 1855, p. 1656 (column 1)

See also: “Miners’ Rights” (entry dated 16 July 1855), Victoria Government Gazette, no. 69, 20 July 1855, p. 1668 (column 2)

“The Miner’s Right” (in the “Domestic intelligence” section), The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 21 July 1855, p. 6 [refers to the Gazette of 20 July 1855]

[32] R. D. Walshe, “The significance of Eureka in Australian history”, in: Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement (2nd edition), Carlton (Vic.): Melbourne University Press, 1965, p. 120

T. H. Irving, 1980, op. cit., p. 142

[33] Dr. R. L. Sharwood, “The Local Courts on Victoria’s Gold Fields, 1855 to 1857” (Melbourne University Law Review, vol. 15, June 1986), Australasian Legal Information Institute

[34] For example: Vincent Pike, “The elective franchise and Miners’ Right”, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.), 12 June 1855, p. 6

[35] “Thames (NZ): 150 Years Ago – Miner’s Rights”, Thames NZ: Genealogy & History Resources, 13 August 2017 [includes images of several Miner’s Rights from Auckland, NZ, from the 1860s]

“First miner’s right”, in: Carl Walrond, “Gold and gold mining”, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand [includes an image of a Miner’s Right from Otago, NZ, dated 1861]

“Image: Miner’s Right certificate”, National Library of New Zealand [includes an image of a Miner’s Right from Canterbury, NZ, dated 1865]

“Papers Relative to Laws on Gold Fields: The Miners’ Right as an Element of Title. Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, 1871 Session I, A-08”, AtoJs Online [Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives and the Votes and Proceedings of the House of Representatives], National Library of New Zealand

[36] T. H. Irving, 1980, op. cit., p. 142 [£1]

“Wages in Australia”, Institute of Australian Culture [1855 pay]

“Recreational prospecting”, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (Victoria) (page last updated 29 June 2023) [“A 10-year miner’s right costs $27 and is for individuals only (not businesses)”]

Jody McDonald, “Average salary in Australia: A guide”, Forbes, 22 June 2023 [Australian annual median salary: $79,800; Australian annual average salary: $90,800]

Updated 4 December 2023

Dear Ed. Welcome Back! With no articles for a long time, I had feared for your health or worse. Great to see that you are back.

My issue: throughout you refer to a Gold License and to a License — all with that spelling; which today is the spelling for the verb, and not for the noun. Am I being ahistorical in expecting that at that time, the modern distinction in spelling differences between the noun and the verb was also extant? Or is that perhaps a later distinction, I wonder?

Hi Raymond,

Thank you for your kind words.

Re the license/licence issue, the name which appeared on the historical documents is “Gold License”. I will be posting nine examples of these, ranging from 1852 to 1854 – they all have the same spelling (I haven’t seen any with a different spelling). Here is a link to the first example: https://www.australianculture.org/gold-license-victoria-hamilton-1852-01/

“License” appears to be one of those words which has changed with time, usage, and fashion. I wonder when the change occurred in Australia?

The Americans use “license” as both a noun and a verb. Interestingly, I have read of spelling situations where the Americans kept the original British usage, whilst the British usage changed. If my memory serves me correctly, the Americans kept -ize whilst the British moved to -ise (e.g. Americanization – pun intended); also, the Americans kept “color”, whilst the British moved to “colour” (influenced by the French).

I’m glad I’m not a foreigner who is trying to learn English – I would probably end up being really confused.

Regards, Ed.

Dear Ed. Once again I thank you for your courtesy in dealing with my seemingly incessant notes in here; and for the one above.

I am following through here, on your comment of not knowing when Oz usage changed from LicenSe for both the noun and verb; to retain that for the verb, and move to LicenCe for the noun. Sadly I cannot give you anything definitive on this, but here are the results of today’s reading trying to find something relevant.

Firstly, from the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary at page 1206: (so this is for the English usage!) & I will expand their abbreviations, hoping that this might make it clearer — but it is still obscure — :

“Licence, substantive (noun), Also license. Middle English, from Old French … The difference of spelling between the substantive and the verb in in accordance with the usage exemplified in practice (substantive), practise (verb) etc. which seems to be based on pairs like advice and advise, where the difference depends upon a historical phonetic distinction. The spelling license has no justification in the case of the substantive. …”.

Ha ha. Gotta laugh at that final sentence, when in their footnotes to this entry they give old examples which do show its use that way.

e.g.: Here is one (which I have edited slightly to aid understanding):

“1. And asketh leve and lycence at lundun to dwell –Langland, William 1330-1400.” {probably better to not also go into the “y” and “i” change here too ! }

“2. Others would confine the license of disobedience to unjust laws. Mill, — but they don’t specify further whether this is James (1773-1836) or John Stuart (1806-1873).”

Now I move on to … “Australian Words and Their Origins” — edited by Joan Hughes:

at page 309: “Licence. Also license….

1820, Hobart Town Gazette: The Licenses for Occupation of Grazing Grounds …

1851, Illustr. Austral. Mag. (Melbourne) … The Commissioner has a busy post, issuing licenses … “.

Thanks again and Best Wishes. Raymond.

I am interested in the wording of the original legislation that allowed miners to occupy land for a dwelling under a Miners Right. Have you see the details of this wording anywhere ?

David.

Prospectors and Miners Association of Victoria..

(established 1980)

Hi David. The wording appears in section 3 of the 1855 legislation which created the Miner’s Right.

““The Miner’s Right” shall … authorise the holder to mine for gold … and to occupy (except as against Her Majesty) for the purpose of residence…”

Here’s the 1855 legislation for you:

https://www.australianculture.org/an-act-to-amend-the-laws-relating-to-the-gold-fields-1855/

It includes a link to the source – a scan of the 1855 Act (8 pages long).

Regards, Ed.

Excellent information re “Miners Rights”, thank you SO much. Researching the Strathbogie Vic, blacksmiths, first time I have heard of them. James Rae’s ‘blacksmith shop was built on land held under a Miners Right’, he was there 1890-1892. Is there anyway I could find which block that was please?

regards Loretta

The Strathbogie Tableland History Group might be a good place to start making enquiries re the blacksmith’s block of land.

https://strathbogietablelandhistorygro.godaddysites.com/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100064515138937

The Strathbogie Shire Council might also be another useful port of call:

https://www.strathbogie.vic.gov.au/

Land Use Victoria (the Lands Department) might also be worth a try:

https://www.land.vic.gov.au/land-registration/for-individuals/where-to-find-information-about-land-titles

The Genealogical Society of Victoria might be able to offer some ideas:

https://www.gsv.org.au/

Last, but certainly not least, the librarians at the State Library of Victoria are a fount of knowledge, so perhaps try them as well:

https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/

I hope those ideas are of some help.