Labourers, farmers, clerks, sailors, policemen — all manner of people — left their usual occupations to take up their new roles as gold miners and prospectors. Unfortunately, the rush of people from their homes and jobs mean that there was a lack of people in the cities and towns.

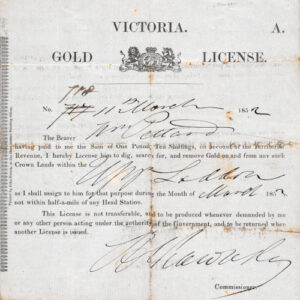

Therefore the Victorian administration dealt with the situation by introducing a Gold License (as notified in the government gazettes of 16 and 27 August 1851), with the new regulations coming into force on 1 September 1851, although the licenses were not issued at Ballaarat until 20 September 1851. The price of a Gold License was set at 30 shillings per month, which was a substantial sum in those days.[1]

The purchase of the license would cost more than two or three weeks’ wages for many people; for example, the usual weekly wage paid to hut-keepers was about 8 to 8.5 shillings; shepherds, about 8.5 to 9 shillings; bullock drivers, 14 shillings; and cooks, 12 to 14 shillings. Since the license was only valid for a month, that meant that any ordinary worker who was not lucky enough to find enough gold to cover at least the cost of their license, as well as their living costs, either had to give up looking for gold, or to continue on illegally.[2]

The miners, quite justifiably, felt that the authorities were treating them badly, and unfairly. The exorbitant cost of the Gold License, the often brutal way in which it was enforced, as well as the arrogance and corruption of the police, led to many protests by miners in Victoria, culminating in the Eureka Rebellion at Ballarat in 1854.

At a mass meeting of diggers at Ballarat on 29 November 1854, diggers were called upon to burn their Gold Licenses. Just a few days later, the Battle of the Eureka Stockade occurred, on the morning of 3 December. The trials of the men who were arrested, and charged with treason, produced a show of public support for the embattled diggers (after a long process, all of the defendants were all found not guilty by the juries in the Melbourne-based trials).[3]

The Victorian government appointed a Goldfields Commission after the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, and the commissioners were given the task of investigating the problems inherent with the situation of the goldfields and the miners. When the Commission finally issued its report, one of its main recommendations was the introduction of a Miner’s Right, with a nominal fee (costing far less than the Gold License); the report recommended a charge of only £1 per year (a recommendation which was subsequently accepted by the government).[4]

So, one of the major consequences of the Eureka Rebellion was the discarding of the Gold License, with its replacement by the Miner’s Right. The era of widespread police oppression and government heavy-handedness against the gold miners of Victoria was finally over.

Relevant resources:

Gallery of Gold Licenses (Victoria)

The Miner’s Right

The Eureka Rebellion

References:

[1] “Proclamation” (dated 16 August 1851), Victoria Government Gazette (supplement to no. 6 of Wednesday, August 13th 1851), 16 August 1851, p. [p. 209] [La Trobe’s declaration that all gold deposits belongs to the Crown; Licenses to be issued]

“Licenses to dig and search for gold” (dated 18 August 1851), Victoria Government Gazette, 27 August 1851, p. [p. 307] [regulations re Licenses to come into effect as of 1 September 1851]

Gold Fields’ Commission of Enquiry, Report of the Commission Appointed to Enquire into the Condition of the Gold Fields of Victoria, &c. &c.”, Melbourne (Vic.): John Ferres (Government Printer), 1855, p. viii, section 6 (PDF p. 9) [“license fee or royalty of 30s. per month”; “the first licenses were issued at Ballaarat on 20th September”]

[2] “Labour report, Geelong”, The Geelong Advertiser (North Geelong, Vic.), 6 January 1851, p. 2 [re weekly wages]

“Wages in Australia”, Institute of Australian Culture [re weekly wages]

[3] “Domestic intelligence”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 27 November 1854, p. 5, column 4 [“a proposal which will be submitted to the meeting, to burn their license papers”]

“Ballarat”, The Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer (Geelong, Vic.), 1 December 1854, p. 4, column 6 [“That this meeting … pledges itself to take immediate steps to abolish the same by at once burning all their licenses”]

“Ballaarat”, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.), 1 December 1854, p. 5, column 2 [“by at once by burning all their licences”; “two bonfires of licenses were made”]

[4] Gold Fields’ Commission of Enquiry, 1855, op. cit., pp. xiii-xiv, section 23 (PDF p. 14-15) and p. 364, Appendix E (PDF p. 439)

Updated 22 November 2023

Leave a Reply