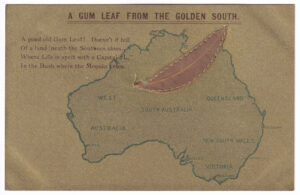

[Editor: This postcard (unused), which incorporates a map of mainland Australia (with a gum leaf made from leather), is undated; however, it is believed to have been published circa 1907.]

[Front of postcard]

A Gum Leaf from the Golden South.

A good old Gum Leaf! Doesn’t it tell

Of a land ’neath the Southern skies,

Where Life is spelt with a Capital “L,”

In the Bush where the Mopoke cries.

[Description: A map of mainland Australia, with a gum leaf (made from leather) attached, accompanied by a poem.]

[Reverse of postcard]

POST CARD.

H&B

Carte postale.

[Manufacturer’s information:]

Harding & Billing’s Post Card

Series 126

An Australian Gum Leaf

Source:

Original document

Editor’s notes:

Dimensions (approximate): 140 mm. (width), 90 mm. (height).

This postcard was manufactured by Harding & Billing. The trademark of Harding & Billing was an artist’s palette with “H&B” in the middle.

A 1907 advertisement for Harding & Billing’s postcards mentions “The Gumleaf from the Golden South” series of postcards, so it is likely that this postcard was published in 1907, or thereabouts (note: the advertisement refers to the postcard having a real gum leaf, rather than one made from leather).

“Harding and Billing publish some very nicely printed Australian post cards. One set, entitled “Nature’s Jewels,” was excellently painted by Mr. Spencer Compton. One bears an illustration (across the map of Australia) of the forget-me-not, another of the wattle, another of the waratah, and each card bears a little envelope containing seeds of the flower represented. Another series deals with “The Gumleaf from the Golden South,” a real gumleaf being attached to each card.”

See: [untitled item] (advertisement), The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, NSW), 12 October 1907, p. 11

See also another postcard from “The Gumleaf from the Golden South” series:

A Gum Leaf from the Golden South [postcard, version 1, circa 1907]

carte postale = (French) “post card”; from the 17th century until the mid-20th century French was considered to be the primary international language in various fields, such as diplomacy, international treaties, and mail, so printing the phrase “carte postale” enabled postcards to be easily identified in the international mail system (similarly, Australian passports in the early to mid 20th century incorporated both English and French in some aspects, e.g. “Passport” and “Passeport”, “Commonwealth of Australia” and “Commonwealth d’Australie”)

See: 1) Jane Doulman and David Lee, “Every Assistance & Protection: A History of the Australian Passport”, The Federation Press 2008, pp. 7, 90 [French as the language of diplomacy; a 1920 League of Nations conference recommended that international passports “should be in at least two languages – the national language and French”]

2) Nuno Marques, “How and why did English supplant French as the world’s lingua franca?”, Babbel, 20 June 2017

3) Katherine, “Why is French considered the language of diplomacy?”, Legal Language Services, 7 December 2016 [“By the 17th century, French was known as the language of diplomacy and international relations throughout the world”]

4) “Postcard history”, Smithsonian Institution Archives [“Many of the private mailing cards, like the Castle postcard seen below, also contained the phrase “Postal Card—Carte Postale,” which indicated that it was allowed to enter the international mail system.”]

5) “Passport – Issued to Esma Banner, by Commonwealth of Australia, 1945”, Museums Victoria [see page 1 of the passport]

6) “List of lingua francas”, Wikipedia [“French was the language of diplomacy from the 17th century until the mid-20th century”]

’neath = (vernacular) beneath

mopoke = a small brown owl, the Southern Boobook (Ninox novaeseelandiae), also known as the Tasmanian spotted owl (also spelt morepoke, morepork) (on a related note, the Tawny Frogmouth is often mistaken for an owl, and has been called a “mopoke” in the past)

Leave a Reply