[Editor: This is a chapter from The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers (5th edition, 1946) by J. J. Kenneally.]

The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers

CHAPTER I.

The “Kelly country” is that portion of north-eastern Victoria which extends from Mansfield in the south to Yarrawonga in the north, and from Euroa in the south-west of the Kelly country to Tallangatta in the north-east. Included in this area are the well-known centres of Benalla, Wangaratta, Yarrawonga, Euroa, Beechworth, Mansfield, Violet Town, Wodonga, Yackandandah, Greta, Lakerowan, Glenrowan, Moyhu, Edi, Whitfield, Myrtleford, Chiltern and Srathbogie.

In the days of the Kellys there was but one railway route in the north-east — from Melbourne to Albury — with a branch line from Wangaratta to Beechworth. Communication between railway townships and those beyond was by road or bush track, and sometimes through country exceedingly hilly and rough. The scattered settlers selected land for cultivation on the river flats and between the ranges and the plains and flat timbered country, while the hilly country provided grazing areas for their horses, sheep and cattle. From Strathbogie to Beechworth was a series of heavily timbered ranges intercepted by rivers and creeks. To-day, along these rivers — the Goulburn, Broken River, King, Ovens, Buckland, and Kiewa — the country is closely settled by a prosperous farming community.

ORIGINAL SETTLERS.

The original settlers were hardy folk — the pick of their respective homelands — and were mainly immigrants from England and Ireland who sought the freedom of a country unhampered by oppressive land and industrial laws. Many of them were obsessed by a sense of the injustice of the laws and of the conditions applicable to rural workers in their homeland, and were determined that in this new home these conditions should not become established. It was not remarkable, therefore, that they regarded with suspicion any attempts to assert “authority,” and were quick to resent any interference with what they considered their liberty in a free land. While the majority of these settlers were undoubtedly honourable and reliable, there was, nevertheless, a leaven of dishonest men who refused to live entirely within the law, and who, by their practices as horse, sheep and cattle thieves, became a source of continuous annoyance and loss to their neighbours, and anxiety to the administrators of the law. Many of them, indeed, acted with such remarkable cunning and discretion that they succeeded in convincing the authorities of their integrity. Their protestations of unswerving loyalty to the Crown and to the maintenance of law and order enabled many of them to attain positions of responsibility, and, as they prospered, they came actually to be regarded as dependable allies of the Administration, while the Kellys were blamed for their crimes.

THE BILLY-JIMMIES.

Billy and Jimmy were two very enterprising and ambitious young men whose parents had come from the well-known island “Great Britain.” They worked together as horse, cattle and sheep thieves, and were very successful, not only in getting away with the stolen stock, but also in escaping from the slightest suspicion as to the actual nature of their calling.

They were expert horsemen and operated in the Mansfield, Benalla and King Valley districts. They were well acquainted with the various districts, and were first-class bushmen. At first they lived in the Mansfield district, but after becoming somewhat regenerated, and, in fact, quite respectable, they acquired interests in the Benalla district, where Jimmy also succeeded in securing the confidence of a section of the ratepayers. Although they had had a serious quarrel over the division of the proceeds of stolen stock, neither of them gave his accomplice away, until, in quite recent years, when Jimmy’s health failed and his end was near. Billy happened to be on a periodical spree, and calling at his favourite hotel, was informed by the landlord that his old mate Jimmy was pretty bad. Billy replied: “I’ll go and see the old ——.” On arriving at Jimmy’s home, Billy entered without knocking and walked into the sick-room, where he met Rev. A. C. McConan, a Presbyterian minister, and a prominent business man, Hugh Moodie. Billy nodded very respectfully to the sick visitors, and then turning to his former partner in crime said:—

“So it is here you are, you old b——, you had better make your peace with God while the parson is here. You remember that mob of bullocks WE stole from —— You remember that mob of sheep WE stole from ——? You remember that lot of cattle WE stole from —— You remember the time WE were sledging hides down the hill to get them out of the way of the police?”

Billy was just getting into his stride when the attendants in the sick-room said that Jimmy could not stand so much excitement, and Billy was rudely bustled out of the house.

The Billy-Jimmy confession spread like wildfire, and the few people who still believed all the accusations against the Kellys now freely admitted that they had wronged innocent people. And it is now generally admitted that the quickest way to get to the Wangaratta Hospital is to say something offensive about the Kellys in the Kelly Country, where stock-thieves are now called Billy-Jimmies.

The members of the police force originated from similar stock, and, as upholders of the law, their display of authority in the circumstances was sometimes a very regrettable one. They were regarded as tyrants and oppressors, and their often rough and ready methods did not tend to dispel the distrust of those whom they were destined to protect. This lack of harmony undoubtedly favoured the Kellys and their followers when driven to resistance in their later career. The Kellys had a multitude of friends, who, if they did not actually aid them, did much to hamper those who were charged with their apprehension.

THE KELLYS

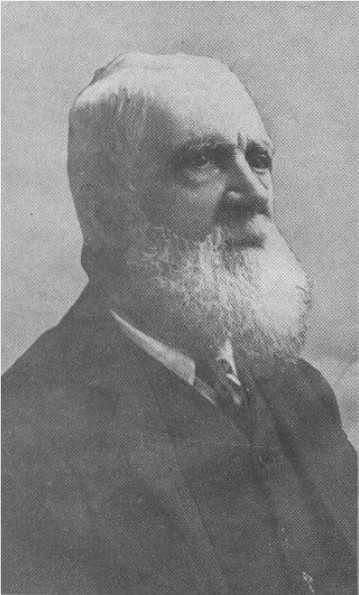

JOHN (RED) KELLY.

John (Red) Kelly, the father of Ned and Dan, was born in Co. Tipperary, Ireland. He was a fearless young man of some education and outstanding ability.

He was the type of young Irish patriot who was prepared to make, even, the supreme sacrifice for hit country’s freedom. He was a man whom the landlords and their henchmen regarded as a menace to the continuation of the injustices so maliciously inflicted on the people of Ireland.

Like the other patriots, he was charged with an agrarian offence (but not assault or murder as falsely stated by the Royal Commission after Ned Kelly’s execution). With jury packing reduced to a fine art, the ruling class in Tipperary had no difficulty in securing his conviction, and transportation to Van Diemen’s Land. Among the Irish leaders who were treated in a similar fashion were:— John Mitchell, Smith-O’Brien, Maher, O’Doherty, and very many others.

After serving his sentence in Van Diemen’s Land, John Kelly came to Melbourne, where he worked for some time as a bush carpenter. The gold fever attracted him to the diggings, where his labours were crowned with success. Returning from the diggings, he bought a farm at Beveridge and settled down to farm life. He married Ellen, third daughter of James Quinn, a neighbouring farmer.

Irish patriotism was such an unforgiveable crime in the eyes of British Government officials in the Colony of Victoria, that even the serving of a savage sentence would not wipe out the campaign of anti-Irish hatred so well organised in the Colonies.

John Kelly was continually hounded by the police, who, without the authority of a search warrant, frequently searched his home without success. The heads of the Police Department were very disappointed. The search continued until, at last, they found a cask with meat in it. John Kelly was arrested and charged with having meat in his possession for which the police said he had not given them a satisfactory account. The long distance from a butcher shop made it necessary to buy meat that would last for some weeks; hence the use of the cask. It is evident that the Bench at Kilmore regarded the charge against John Kelly as a “trumped up affair”; he was sentenced to only six months. Now, if John Kelly had been charged with cattle stealing as frequently stated by the enemies of Honor, Truth and Justice, he would have received a sentence of, at least, five years.

Although the sentence was for only six months, it proved to be a Death Sentence. Such was the treatment to which John Kelly was subjected in the Kilmore Jail that, notwithstanding his good health and perfect physique when sentenced, he died shortly after his release. Broken in health, he now sold his farm to conduct a hotel at Avenel. Shortly after his arrival at Avenel, John Kelly died.

MRS. KELLY.

Shortly after her husband’s death, Mrs. Kelly, with her eight orphans, left Avenel for Greta, where her brothers had already taken up land. Here on the Eleven-Mile Creek, five miles from Glenrowan, and eleven miles from Benalla, the Kelly family contrived to make a living, some by working for wages, and the others by improving their selection. It was apparently an uphill struggle, and their difficulties were considerably increased by the unwarranted attentions of the police in their determination to carry out the instructions of the Assistant Chief Commissioner of Police, Superintendent C. H. Nicolson, to “root the Kellys out of the district.” At the time these instructions were given, there were no charges impending against any member of the Kelly family. It is very evident, therefore, that the police, metaphorically speaking, intended to use LOADED DICE to rob the Kelly family of their FREEDOM. It is only natural, therefore, that the Kellys developed a strong resentment to the attitude of the local police, and an equally strong dislike for the Police Force. Notwithstanding this systematic persecution the police failed to justly convict Ned and Dan Kelly of a felony.

A jury, consisting of the population of Greta, by their attitude, gave a most emphatic verdict that Ned Kelly’s conviction, over the McCormack affair, was a most outrageous Miscarriage of justice. The same jury was equally emphatic in their verdict that the conviction of Ned Kelly in connection with the search for Wild Wright’s horse, was also an outrageous Miscarriage of Justice. Therefore, the only honest conviction (even with loaded dice) was his resistance to four policemen and a bootmaker when trying to handcuff him at Benalla in 1877, seven years after the introduction of the infamous methods already referred to as “Loaded Dice.” On this occasion Ned had to pay £3 1s., which covered the fine, costs and damage to police uniforms.

Added to their inherited resentment of oppression, the Kellys developed a bitter hatred of the law as it was then administered, and herein lay the origin of their subsequent career of resistance and defiance.

Some time after settling on the Eleven-Mile Creek, Mrs. Kelly married a neighbouring settler — George King — who came from California, North America. There were three children of the marriage, which was not a happy one. Ned Kelly thrashed King for ill-treating his mother. King left Greta never to return. King was not liked in Greta, and the local residents continued to refer to his wife as Mrs. Kelly. Therefore, for the purposes of this history, Ned Kelly’s mother will be referred to as Mrs. Kelly, notwithstanding the fact that she was the lawful wife of George King.

Mrs. Kelly died at Greta on the 27th March, 1923. She had married King on the 19th February, 1874, at Benalla. She was then 36 years old. King’s age was 25 years. Therefore, Mrs. Kelly was 85 years old when she died, not 95 years as was generally supposed. Mrs. Kelly and her family were very highly respected and loved by the people of Greta. This is very vividly demonstrated by the outstanding fact that although over sixty long years have passed away, no one can, with impunity, say one word against the Kellys in the district where they were best known.

As already stated, Mrs. Kelly died on the 27th of March, 1923, although the writer of a diabolical concoction, in book form, called “Dan Kelly,” stated in his book that Dan Kelly’s mother had died many years prior to 1911. But then, previous writers of Kelly Gang books seem to have taken great care to mislead their readers while they revelled in the suppression of Truth and the replacing of it with fiction.

Shortly before her death, Mrs. Kelly’s name was entered at the Wangaratta Hospital as Mrs. King, with the result that the hospital staff were unaware that their patient was the mother of Ned Kelly.

Mrs. Kelly steadfastly refused to give any information about her family to the numerous newspaper reporters and travelling journalists who frequently visited her home, and she bluntly refused them any information about her sons. But to her intimate friends she talked freely, and displayed great pride in her sons. She always maintained that Danny was a better general than Ned, and would relate how Danny, though only 17 years old, put Heenan’s hug on Constable Fitzpatrick and threw him on the broad of his back on the kitchen floor. Nevertheless she recognised Ned’s general ability, and when speaking one day to a visiting journalist with whom she had been favourably impressed, she said: “My boy Ned would have been a great general in the big war — another Napoleon — whichever side he was on would have won.”

NED KELLY.

Edward (Ned) Kelly was born at Wallan Wallan, Victoria, in the year 1854, and was the eldest son. He was strongly influenced by the unjust treatment meted out to his father by the authorities at home and abroad. His father’s death from prison treatment after serving a sentence of only six months on a “trumped-up charge” of having a cask with meat in it in his possession, intensified his distrust in the honesty of the police of that day. When Inspector Brook-Smith searched Kelly’s home at Greta prior to the fight with the police at Stringybark Creek, he found meat in a cask and threw it out on the ground floor; but no one was arrested or charged “having meat in their possession for which the police said they had not been given a satisfactory account.” Now, it were a felony for John (Red) Kelly to have meat in a cask at Wallan Wallan, why was it not also a felony to have meat in a cask at Greta?

In the early part of 1870, when Ned Kelly was 15 years old, he was arrested and charged with having held the bridle reins of Harry Power’s horse, when Power, a bushranger, waylaid a Mr. Murray at Lauriston near Kyneton. As the police failed to produce any evidence of identification, Ned Kelly was discharged; but they (the police) were able to gloat over the fact that Mrs. Kelly, a widow with eight orphans, had to provide money for her son’s defence.

Next day Ben Gould assisted the Kellys in branding and castrating calves, and decided to play a joke on McCormack.

Having no children Mrs. McCormack always accompanied her husband when hawking in the country. Gould made up a parcel of giblets taken from the bull calves and attached a note containing directions which, if followed, would increase the population, so much needed in a new country. Gould then handed the parcel to Ned Kelly, who, in turn, handed it to a younger boy, Tom Lloyd, saying: “Give this to Mrs. McCormack.” The lad did as directed saying: “Ned Kelly gave me this parcel for you.” McCormack and his wife were annoyed at the rude joke. A few days later Ned Kelly was passing McCormack’s camp; the latter saw him coming and determined to give Ned a good thrashing, to teach him manners with a stick. McCormack appeared and blocked the track. Ned could neither escape to the right or to the left, and as McCormack advanced to waylay him, Ned jabbed his spurs into his horse, which made a sudden bound forward, knocking the aggressor down. Ned went on his way rejoicing at his escape. Bruised and defeated McCormack went to the Greta Police Station and laid two charges against Ned Kelly. He charged Ned with having sent his wife an obscene note, and with having committed a violent assault on himself. Ned was arrested, convicted and sentenced to three months on each charge.

This was the first win for the Assistant Chief Commissioner of Police, Supt. C. H. Nicolson, who played for the forfeiture of Ned Kelly’s freedom with, metaphorically speaking, “Loaded Dice,” as the following will prove even to the most sceptical. — Supt. Nicolson reported to Capt. Standish as follows:—

“I visited the notorious Mrs. Kelly’s house on the road from hence to Benalla. She lived on a piece of cleared and partly cultivated land on the roadside, in an old wooden hut with a large bark roof. The dwelling was divided into five apartments by partitions of blanketing rugs, etc. There were no men in the house — only children and two girls about 14 years of age, said to be her daughters. They all appeared to be existing in poverty and squalor. She said her sons were out at work, but did not indicate where, and that their relatives seldom came near them. However, their communications with each other are known to the police.

“Until this gang (sic) referred to is rooted out of the neighbourhood, one of the most experienced and successful mounted constables in the district will be required in charge of Greta. I do not think the present arrangements are sufficient. Second-class Sergeant Steele of Wangaratta keeps the offenders (sic) referred to under as good surveillance as the distance and means at his command will permit. But I submit that Constable Thom would hardly be able to cope with these men. At the same time some of these offenders may commit themselves foolishly some day, and may be apprehended and convicted in a very ordinary manner.”

When the above was written there was no charge, of any kind, pending against any member of the Kelly family. Yet they were referred to as offenders.

The above report was brought forward in evidence before the Royal Commission in June, 1881, and was further added to by the following evidence given on oath by the Assistant Chief Commissioner of Police, Supt. C. H. Nicolson, as his brazen confession of having used, metaphorically speaking, “Loaded Dice.”

“This (the foregoing report) was the cause of my instructions to the police generally, and I had expressed my opinion since to the officer in charge of that district, that without oppressing the people or worrying them in any way, he should endeavour, whenever they committed any paltry crime, to bring them to justice and send them to Pentridge even on a paltry sentence, the object being to take their prestige away from them, which was as good an effect as being sent to prison with very heavy sentences, because the prestige those men get up there from what is termed their flashness helped to keep them together, and that is a very good way of taking the flashness out of them.”

Although Supt. Nicolson, as Assistant Chief Commissioner of Police of Victoria, used the above quoted Loaded Dice in playing to forfeit the freedom of members of the Kelly family, he was doomed to failure. The Royal Commission caused his removal from the Police Force in the Police Purge of 1881.

A young man named Wild Wright had been working in the Mansfield district, and decided on a visit to his relatives at Greta. He considered the distance too far to walk, and he had no other means of transport. He, however, preferred to ride, and without asking permission, took the mare belonging to the local schoolmaster. On arrival at Greta he turned the animal into a paddock pending his return journey. His holiday over, he discovered that the horse had got out of the paddock and wandered away. Wright now enlisted the help of Ned Kelly in the search. Ned believed the mare belonged to Wright. In the meantime the schoolmaster had reported the disappearance to the police, and a description of the animal had already been published in the “Police Gazette.” It was unfortunate for Ned that he had succeeded in the search, for, when leading the horse back through Greta, to return it to Wright, whom he believed to be the rightful owner, he was intercepted by the local constable in front of the police station. Constable Hall, who was in charge of Greta, was struck by the resemblance, the mare Ned was leading, bore to the one reported as having been stolen from the schoolmaster near Mansfield.

Without inquiring how or why Ned Kelly became in possession of the stolen horse, Constable Hall attempted to be somewhat diplomatic, and invited Ned to come into the police station to sign a paper in reference to Ned Kelly’s recent discharge from the Beechworth gaol. Ned replied: “I have done my time, and I will sign nothing.”

The constable thereupon attempted to drag Ned Kelly from his horse, apparently for Ned’s refusal to sign the fictitious paper. Ned jumped off his horse on the off-side. He was promptly seized by the burly constable and thrown to the ground. Ned fought like a wild cat. As the constable was holding this sixteen years old lad down, the latter thrust his long spurs with considerable force into the policeman’s buttocks. Hall, answering promptly to the spurs, made a flying leap forward, covering several yards.

Ned Kelly, regaining his feet, made a run for his horse. There were 14 brickmakers working close by, and some of them were attracted to the scene. One of the brickmakers seized the sixteen years old lad by the legs and brought him down. The policeman was so angered by the injury inflicted on his dignity by Ned Kelly’s spurs that he threw himself on the prostrate lad and savagely belaboured him on the head with his revolver. Ned was badly cut about the head and bled freely. He carried the scars to the end of his life. So freely did Ned bleed that his clothes were thoroughly saturated with blood, and when dried, his clothes were stiff enough to stand up.

He presented a dreadful sight when brought before the Wangaratta Court next day, and the spectators commented severely on the brutality of the police when arresting a mere boy.

Wild Wright was also arrested and charged with “horse stealing”; Ned Kelly was charged with “receiving,” knowing the horse to have been stolen. They were tried and convicted. No one can beat Loaded Dice, particularly when used departmentally.

Ned Kelly was sentenced to, three years for “receiving” under the above circumstances.

Wild Wright was sentenced to 18 months for deliberately stealing the horse. The Loaded Dice was not used against him.

It is alleged that one James Murdoch, who was afterwards hanged for murder at Wagga Wagga, N.S.W., received £20 from Hall to give evidence against Ned Kelly.

The police always admitted that Ned Kelly was no fool. Therefore, he would not lead Wright’s mare in front of the Police Station if he knew she had been stolen. This second most outrageous miscarriage of justice created intense anger in the Greta district, and developed, in those who knew the facts, supreme contempt for the police, who described the settlers of Greta as a lawless people.

The attitude of the police and the judiciary as stated above destroyed the last ray of hope which the Kellys, their relatives, friends and sympathisers may have had of obtaining a fair deal from the police and the judiciary while the Dicewere still loaded and on active service against them.

Ned Kelly was discharged from goal in 1874 after serving his second sentence, the result of fiendish persecution by the police.

Constable Thomas Kirkham, who in after years was one of his pursuers, stated that Ned Kelly was a fine manly man, and possessed a high moral character; that his conduct in gaol was exemplary in every way.

Notwithstanding the pressing anxiety of the police to bring the Kellys up on any charge, no matter how paltry, it was not until 1877 that that Ned Kelly experienced further police hostility.

During a visit to Benalla in that year, he was arrested on charges of being drunk and with having ridden his horse across a footpath. He asserted that on this occasion his liquor had been drugged, and vehemently protested against being charged with drunkenness. When he was being brought next morning from the lockup to the Court House, he escaped from the constable in charge of him, and took refuge in the shop of King the bootmaker. He was pursued by the Sergeant and three constables, who, with the assistance of the bootmaker, tried to handcuff him. A fierce fight ensued, the odds being five to one — four policemen and the bootmaker against Ned Kelly. In the fight Ned Kelly’s trousers were literally torn off him. Constable Lonigan, taking advantage of the torn garment, seized him by the privates and inflicted terrible torture on his victim.

In order to make sure that the police would not inflict any further violence on their prisoner, the J.P. accompanied him to the Court where the sum of £3 1s. paid for the fines, damages to uniforms and costs. (It was Supt. Hare who, in later years, described Ned Kelly as the greatest man in the world.)

This fine was the only genuine conviction ever recorded against Ned Kelly prior to his being driven to the bush to become a bushranger.

To the everlasting discredit of a large section of Australia’s bitterly anti-Kelly Press and equally bitter anti-Kelly authors of so-called Kelly Gang books, the Australian and overseas publics were led to believe that Ned Kelly must have had at least from 20 to 30 prior convictions against him before being outlawed. Whereas the foregoing four charges are the only charges ever made against Ned Kelly before being outlawed. These four charges are as follow:—

(1) The first, holding bridle reins of Harry Power’s horse, was dismissed.

(2) The second, the McCormack affair, a conviction — an outrageous miscarriage of justice.

(3) The third, a schoolmaster’s horse, a conviction — also an outrageous miscarriage of justice.

(4) The fourth, drunk and riding across a footpath and resisting the police, the only genuine conviction, which £3 1s. settled.

Now, if the situation were reversed, and four Kellys and a bootmaker attacked one policeman, and with this terrible odds, one of the Kellys grabbed the policeman, as Lonigan grabbed Ned Kelly, what would the anti-Kelly Press and the depravity of anti-Kelly authors have published?

Although Ned Kelly suffered severely from the injury inflicted on him by Lonigan, he thought no more about the prophecy in reference to the shooting of him.

That prophecy, however, preyed on Lonigan’s mind and when he was ordered to join Sergeant Kennedy’s party, he expected something unusual to happen.

He had a premonition that Ned Kelly’s prophecy would come true. Ned Kelly had not recognized Lonigan when he fired the fatal shot; he thought he was shooting at either Flood or Straughan. That prophecy!

KATE KELLY.

It was the police who made a heroine of Kate Kelly, when deceived by the exhibitions of expert horsewomanship freely given, for their benefit, by Steve Hart, when, dressed as a woman he rode about in side-saddle. Therefore, whenever they saw an equally expert exhibition of horsewomanship by Mrs. Skillion (nee Margaret Kelly) with whom they were not acquainted, they jumped to the conclusion that it was Kate Kelly who was also a first-class horsewoman.

It was Mrs. Skillion, some years older than Kate, who possessed the unlimited confidence of her brothers and their mates. It was Mrs. Skillion who was always in close touch with her outlawed brothers and supplied them with the necessaries of life. Kate did not, at any time, play an important part in her brothers’ affairs. It was Mrs. Skillion who frequently led the police, who were on foot, on many a wild goose chase over rough and extremely difficult country. Although mounted on a good horse, she allowed the footsore police to keep her in sight. They were sure that the bulky bundle she carried on the saddle was supplies for the outlaws. When satisfied that the exhausted police could not be on active service for some days, she spurred her horse, and, lost in the timber, returned home well pleased at the success of her strategy.

Kate Kelly, though thoroughly loyal, was too young to possess that mature judgment and discretion with which her elder sister, Mrs. Skillion, was so gifted. It was this lack of discretion and judgment that caused Kate to be led into appearing on the stage of a Melbourne theatre the night after her brother was executed.

It was Mrs. Skillion who, with Tom Lloyd, went to Melbourne for ammunition and successfully fooled Rosier and the police. And it was Mrs. Skillion who knelt between the charred remains of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart and delivered the most scathing invective on the savagery and cowardice of the police at the siege of Glenrowan.

DAN KELLY.

Dan was the youngest of “Red” Kelly’s three sons. All accounts of him show he was of a quieter and less forceful nature than his brother Ned, although the general public have been led, through the vicious misrepresentation by the police, to regard him as a treacherous and blood thirsty scoundrel. This misrepresentation was encouraged to some extent by the remarks of his brother Ned when addressing the men imprisoned in the storeroom at Faithful’s Creek station near Euroa. In order to prevent anyone from attempting to escape Ned Kelly said: “If any of you try to escape, Dan Kelly and Steve Hart will shoot you down like rabbits just for the fun of it.” This was taken literally, and Dan Kelly was regarded by those who were not personally acquainted with him as a bloodthirsty ruffian. Although he was regarded as an outlaw from the time he was 17 years of age till he was 19 years at his death at Glenrowan, he killed no one, he shot no one, offered violence to no neighbour and insult to no woman.

CONSTABLE FLOOD.

In his anxiety to carry out Supt. Nicolson’s instructions to root the Kellys out of the district, Constable Ernest Flood, in 1871, arrested Jim Kelly and his little brother Dan. Jim was about 13 years old and Dan was only 10. Jim was employed by a local farmer, with whose consent he rode one of his employer’s horses for the purpose of going home to see his mother. He met Dan on the way and took him on the horse behind the saddle. Before going much further they were intercepted by Constable Ernest Flood, who arrested the two children on the charge of illegally using a horse.

Senior-Constable Flood gave evidence on oath before the Royal Commission on the 29th June, 1881, as follows:—

Question by Commission: Did you prosecute the members of the Kelly family continuously while you were in that district?

Constable Flood: “I did, a good number of them. I could give the names.” (Looking at his notebook.)

Question. — Try and do that and give about the dates. — I arrested James and Dan Kelly when they were mere lads for illegally using horses in 1871. They were discharged on account of their youth and their intimacy with the owner of the horses, one of the brothers having been a servant of the person who owned the horses.

Answering another question, Senior-Constable Flood said: “I think Mr. (Superintendent) Barkly had a great deal to do with the removal of men. I know he had me removed, and I was much aggrieved at the way he got me removed.”

Question. — What reason did he give you? — There was a charge preferred against me by a man named Brown, a squatter at Laceby, and an investigation was held by Mr. Barkly over it. I was treated most unfairly in the matter.

Question. — He (Brown, the squatter) charged you with going amongst his horses and disturbing them? — Yes.

Seeing that the Kellys were blamed for all the horses stolen in that district, it would not do to charge Constable Flood with being a suspected horse thief. Supt. Barkly, therefore, removed him from Greta to Yandoit, near Castlemaine, where there were only a few working horses, and consequently no temptation to disturb or interfere with them.

The inference behind the charge against Flood was that he either stole or planted horses and then blamed the Kellys or their relatives for the offence.

For the next five years no charge of any kind was made against Dan Kelly, but at the age of 15 years he was charged with having stolen a saddle, and notwithstanding the anxiety of the police to convict, the evidence they adduced failed to impress the bench, and the little boy was again discharged. But perseverance brings its reward, and on the following year Dan Kelly was charged with doing wilful damage to property.

The bench accepted the evidence of the owner of the property, D. Goodwin (who was afterwards sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for perjury in connection with the same property), and Dan Kelly was at last convicted and sentenced to three months in gaol. This was the only conviction against Dan Kelly before being outlawed.

On the following year someone at Chiltern lost a horse, and the police took out a warrant for Dan Kelly, and this was the unfortunate warrant which brought about the Fitzpatrick episode. One of Dan Kelly’s cousins was joined with him in this case of alleged horse stealing.

The cousin was arrested, and as there was no evidence to commit, he was discharged. This discharge also cleared Dan Kelly.

Because he was the elder, and because, perhaps, he was possessed of more initiative and determination, Ned Kelly assumed the leadership, and in several instances asserted himself and evinced his mastery. On one occasion the two brothers quarrelled, and Dan, determined to clear out, went over to his cousin’s homestead for a couple of days. Ned followed him and became reconciled, reminding Dan that their only hope of maintaining their freedom was by sticking together. He also reminded Dan of the past injuries they had experienced at the hands of the authorities, and prevailed upon Dan to return home. There were three occasions on which Dan differed from Ned in the carrying out of their plan of campaign, and subsequent events proved that in each case Dan was right. The first difference occurred at the battle of Stringybark Creek, when Dan wanted to handcuff McIntyre. The second was Dan’s objection to the Glenrowan program, and the third was when Dan suggested that Constable Bracken should be handcuffed to the sofa in Mrs. Jones’ Hotel. While their mother had great pride in Ned’s ability to lead, she always maintained that Danny was a better general than Ned.

STEVE HART.

JOE BYRNE.

Joe Byrne was a native of Beechworth, and of the members of the gang appears to have had the least provocation for defiance of the law. While still in his ’teens he was intimately associated with Aaron Sherritt, with whom he was convicted of having meat in his possession suspected to have been stolen. Joe Byrne’s voluntary association with the Kellys appears to have been the result of that hero worship which creates so strong an impression upon some natures.

The fact that the police never intercepted him was due either to the cleverness of Joe Byrne or to the incompetence and insincerity of the police. With his revolver he rarely, if ever, missed a two-shilling piece thrown in the air.

Such were the youths who comprised the famous Kelly Gang, and such was their fame in police circles that almost every crime committed in the North-Eastern district of Victoria was attributed to their activities. There can be very little doubt that the contemptuous disrespect which the Kellys and their friends held for the authorities was considerably increased by the many crimes and misdemeanours that were thus wrongfully attributed to them. Undoubtedly, also, such groundless charges tended to increase the sympathy and practical assistance of their friends and neighbours for those who, they considered, were denied what they termed “equal justice.”

THE ADMSSION.

After the capture of Ned Kelly at the “Siege of Glenrowan” some of the truth leaked out. Inspector Wm. B. Montfort, who succeeded Superintendent Sadleir at Benalla, gave evidence before the Royal Commission on 9th June, 1881, as follows:—

Question by Commissioner: If there was frequent crime in the district undetected, and the offender not made amenable to justice, would you not know that the man (policeman) stationed there was more than likely inefficient?

Inspector Montfort: Not necessarily.

Question: Would the book show the action the constable took on that information?

Inspector Montfort: It would only show that he made inquiries in a general way; it would not give the details. For instance, two men might come over from New South Wales and go to Moyhu and steal horses there, and successfully pilot them across into New South Wales, and it would be a difficult thing to make the police officer responsible for that. It does not necessarily follow that the thieves live in the district. In answering another question, Inspector Montfort said: “When I went to Wangaratta in 1862 the great trouble the police had then was with the Omeo mob of horse stealers. They used to come across to Wangaratta, steal horses, go to Omeo, and plant them in the range and alter the brands, and sell them in Melbourne or in New South Wales. I could mention the names of the parties. There is still the same complaint (June 9, 1881). That is why I consider the doing away with the Healesville station was a great mistake at the time.” This clearly proves that the police knew that the horse stealing in the Kelly Country was not done by the Kellys.

In order that Inspector Montfort might now speak with even greater freedom, the Royal Commission took the following evidence from him, on oath, behind closed doors:—

Question: How was it that, on the prosecution of MeElroy and Quinn there, they were not made amenable to some sort of justice to keep them quiet?

Inspector Montfort: The case against McElroy was not proved. The charge was that he snapped a loaded gun at Quinn with intent to do him grievous bodily harm, and that was not proved to the satisfaction of the justices. It was sworn to right enough by Quinn, but the justices did not believe him. There was subsequently a cross-summons taken out by McElroy against Quinn for some alleged insulting language made use of by Quinn at Mrs. Dobson’s public-house (at Swanpool). It is usual in the bush to have cross-charges made. I suggested to the bench that they should postpone the hearing of the case against Quinn for a week, but they decided they would hear it to-morrow (June 10, 1881). I did that because I considered that Quinn was taken by surprise; that he, in ignorance, trusted me to defend him, when I had no status in the court to do anything of the kind, and I considered that it would be treating him with injustice not to let him have the option and opportunity of employing a solicitor.

Question: You were prosecuting McElroy?

Inspector Montfort: Yes. I might say, in connection with this, that a great deal of the difficulty with these men (Kellys and their friends) would be got over if they felt they were treated with equal justice — that there was no “down” on them. They are much more tractable if they feel they are treated with equal justice.

This admits police persecution in the form of Loaded Dice, and could be admitted only behind closed doors.

Source:

J. J. Kenneally, The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers, Melbourne: J. Roy Stevens, 5th edition, 1946 [first published 1929], pages 18-47

Editor’s notes:

Co. = an abbreviation of “County”

Van Diemen’s Land = the island, now known as Tasmania, originally named Anthoonij van Diemenslandt, by Abel Tasman, in honour of Anthony van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies

Wm. = an abbreviation of the name “William”

[Editor: Corrected “plan of compaign” to “plan of campaign”; “Van Dieman’s Land” to “Van Diemen’s Land” (in two places); “a lawless” to “as a lawless”; “Stringbark Creek” to “Stringybark Creek” (in graphic caption re. Lonigan). Added a comma after “charge of Greta”. Deleted second colon after “Ned replied:”.]

Leave a Reply