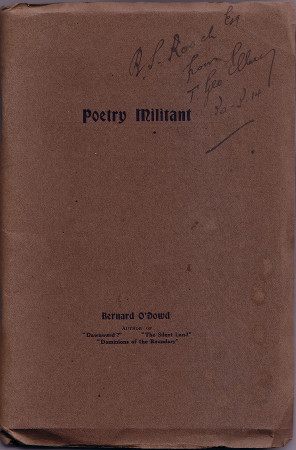

[Editor: A booklet by Bernard O’Dowd, published in 1909.]

Poetry Militant

An Australian Plea for the Poetry of Purpose.

By

Bernard O’Dowd

Author of

“Dawnward?” “The Silent Land”

“Dominions of the Boundary”

Melbourne:

T. C. Lothian, 226 Little Collins Street

1909.

First Impression June 4, 1909.

Poetry Militant.

An Australian Plea for the Poetry of Purpose.

It is hardly surprising that commercialism, the passport to physical prosperity, should be the prevalent idea of an age, when, through the disintegration of class-rule, prosperity is for the first time in history possible for all; nor is it surprising that the masses, stupefied from time immemorial in the cavern of Pain, hereditary and inescapable Pain, should, when released at last a little, drink some madness from the unaccustomed sun, and follow, as they do to-day, Pleasure for Pleasure’s sake, even over the precipice: nor, moreover, is it surprising that the vast majority of the people, educated, though it be but with a smattering, for the first time in history, should not yet to any great extent be partial to poetry, the final flower of the human intellect.

But one of the functions of a lover of literature in a community hypnotised by commercialism, and the guiding motif of whose leisure-life is “Pleasure for Pleasure’s sake,” is when he can, to re-state with emphasis, fanatic emphasis if necessary, the claims of the intellectual and spiritual powers of the mind to due consideration. It seems therefore not inappropriate that one who holds the calling of the literary man sacred, should, since a due occasion has arisen, stress the note of the importance of that calling, examine the theories of artistic conduct practised by those who follow that calling, and try to summon from the wilderness where they wander, often unheard, often unconscious, those fitted to gird on the robes and strike the high harp of that calling.

In the dislocations of a transition period, when the power of the theologian over the masses is waning, and the stars of other dogmatists, possibly more dangerous, because more superficially rational, are rising above the horizon, the function of the poet as permeator of the masses with the high ideals communicated to and communicable by him, grows more important. It is mainly by him, for instance, I contend, that the discoveries of science and the contributions of philosophy are made emotionally digestible for the people. He too, moreover, is the most potent disinterested watchman for awakening the people to a sense of the wrongs they endure or inflict; and thus he is the Baptist of his epoch, preparing in its wilderness the Way of the Lord.

I should say now that I am speaking here of the creative poet, and not of the mere singer of word-tunes, the mere verbal tickler of jaded ears. The latter occupies an interesting enough subordinate position among the caterers of the minor pleasures of the world, but the creative poet is the only one that really matters as an enduring factor in progress.

I hold that the real poet must be an Answerer, as Whitman calls him, of the real questions of his age, that is to say, that he shall deal with those matters which are, in the truest sense, interesting, and in the noblest sense useful, to the people to whom he speaks. It is a heresy of the modern stylist that has done a lot of harm and deprived the people of guidance necessary for them, that subjects in which they are intensely interested, such as politics, religion, science, sex and social reform, are not usually fit subjects for poetic treatment. Is it any wonder that poetry is not read nowadays, when subjects that are the staple of the interesting mental life of practically everybody are ignored by so many of the most technically accomplished poets?

In the literature of the Church we frequently find the state of the Church on earth and its subsequent state when the scroll of matter shrivels, referred to as The Church Militant and The Church Triumphant. I claim of poetry, too, that it has its stages, one while we are on our pilgrimage, and one when we have attained the goal, Eternal Beauty — that is to say, there is a Poetry Militant and a Poetry Triumphant. One complaint I have against the disciples of the “Art for Art’s sake” shibboleth, for instance, is that they demand the Triumphant stage without carrying out the duties of the Militant stage. We have indeed in a fighting age a little too much of the Poetry Triumphant, Poetry for Poetry’s sake, and not at all enough of the Poetry Militant, the poetry that helps man to win the battles that constitute the days of his pilgrimage. Poetry Triumphant, Poetry for Poetry’s sake, both mean Poetry Absolute, and, in the age of the philosophy of the relativity of all things human, I need hardly say that there is no such thing as Poetry Absolute. Indeed, an important fallacy in the doctrine of “Art for Art’s sake” lies in this implication of the possibility on earth of Art Absolute, Poetry Absolute. What the upholders of the doctrine really mean, however, is that we should pursue Art for Past Art’s sake, pursue Poetry for Past Poetry’s sake; that we should examine the Art of the past, the Poetry of the past, glean from the forms which that Art and that Poetry found most apt for its expression a series of rules, apply those rules to all subsequent creations of the artistic or poetic imagination, and damn beyond appeal every creator brave enough, artistic enough, poetic enough to dare to express a new thought, or frame a new form. My reply to that is simply that I decline to allow the right of the infant Past to govern the growth of the adolescent Present and the adult Future.

You will thus see the relation between the doctrine of “Art for Art’s sake,” and what I subsequently refer to as the “Yoke of the Classical,” and will also understand why I call “Art for Art’s sake” a useful dogma for the student, the beginner in art and poetry, but not at all a necessary or even advisable doctrine for the artist or poet in the real work of his life.

It is Poetry Militant I preach, and, as far as I can, wish to practice, and when at times, tempted mayhap by the sight of Australian Claude Lorraine picnic girls playing “drop the handkerchief” on a lush green meadow ringed by the fairy gold of the whispering wattle trees, I turn from the macadam to rest in a nook in a paddock dainty with maiden-hair and festooned with “supple-jack,” and attempt to lilt a fragment of the melodies of Poetry Triumphant, I have a very uneasy feeling that I am loafing and embarrassing the vanguard by an unwarrantable self-indulgence.

Poetry Militant has chief regard to the end in view, the furtherance of the best interests of the human race by means of the subtle artillery entrusted to it — that is to say, it denies that the Useful is forbidden entrance into Poetry, nay, it claims that Poetry without the Useful in it, disguised may be but there, is not in this stage of our race’s progress, poetry at all. But the doctrine of “Art for Art’s sake” lingers so persistently in spite of the fists of the moralists and the practice of the greater poets and artists, that one is compelled to examine it to see if after all there is a truth in it. I think that there is a truth in it at two points in the career of the artist, namely (1) in his school life when he is learning the methods adopted by practitioners of his art in the past, and (2) in the other world — if there indeed he has no longer any need to use Art to make this world better, and may accordingly without qualm of conscience pursue it for its own beautiful sake.

The earth-life of the artist has two stages, the school or apprentice stage, and the adult or master stage. This brochure is partly a protest against the undue intrusion of the disciplinary dogmas of the school into the adult works of the artist, and partly a call to Australian literary folk that it is time to leave school and get to work.

What do we do at school?

We learn five finger exercises, and woe to the pupil who digresses into the Marseillaise!

We chloroform a simple word into a predicate, or an attribute, or a participle, or a nominative absolute, and woe to the pupil who cries “Mumbo Jumbo”!

We comb the hairs of our mistress’s eyebrow with the fourteen jewelled teeth of a sonnet, but woe to the pupil who glances reproachfully at the dead heron in her hat!

We chop the logs of yesteryear into regulation ballade lengths, and pile them before the throne of the Prince of Nowhere-in-Particular, but woe to the pupil who would dare suggest to a real prince, say, the reprieve of a condemned criminal in, say, a Ballade of the Hanged!

The laws of the schoolroom, necessary for the student, may be baneful, if dogmatically practised to the letter in real life. The work of the student is how to use tools; the work of real life is to use them, not for the sake of using them, but for the furtherance of life. In the schoolroom, form is our object, and is consciously pursued, so that we may learn to use it automatically; but in real life, form consciously pursued produces but baby toys, “Teddy Bears.” The high seriousness rightly demanded of the true poet is hardly possible in writing beautiful poems that say nothing. Dead five-finger exercises teach the hand to play spontaneously, without thought of five-finger exercises, sonatas and nocturnes, which are life. Don’t let us, however, make the be-all and end-all of poetic life mere five-finger exercises! “Art for Art’s Sake,” that useful standard of the school-room, ignores utility, so that beauty of handling shall become automatic. But Parthenons that shelter, Madonnas that soothe, Aphrodites that inflame us to physical robustness, Macbeths that terrify the furtive ambitions from our souls, Miltonic Samsons that pull our Philistine pillars down, and Norman Lindsay leers that remind us so pitilessly of the fearful skeletons left by the Past in our own cupboards — these are no products of the slaves of the schoolroom lamp — they are for use!

One reason why I am raising this question of Poetry Militant is because, admitting, of course, a number of important exceptions, I think that contemporary poetry is saying nothing in a multitude of beautiful words, phrases and forms. And while the poets are making of poetry a beautiful morass of ferny forms, mossy forms, and fungoid forms accessible, by the way, only to the very few, there is nothing solid in it to sustain any but the incorporeal wayfarer. The misdirected energies of too many modern versewriters are being wasted in making crazy quilts out of pretty words; while a hungry and thirsty world, deprived of so many of its traditional nurses, is languishing for the help the poets can give it.

The poet is the true Permeator, the projector of cell-forming ideals into the protoplasmic future. He is a ferment who alters for the better the ordered, natural, inert sequences of things. He is a living catalyst in the intellectual laboratory, and does in a moment what in the regular order would take us an age to do. He is the necessary hurrier of the evolution process. Science and Ethics reveal the Brute Will of the world in operation, Poetry is the Idea that deflects that Will and rides it to new and better operation.

And at no time in the history of the world was the need for the Permeator poet, the projector of ideals, the Poet Militant, greater than in the present reconstruction of all things beneath the wand of Evolution theories, and in no place greater than in this virgin and unhandicapped land of social experiments, embryonic democracy, and the Coming Race, Australia!

Evolution has commanded the bones that have been parching in the valley for ages to come together again, to be knitted with sinews and clothed with flesh and skin; but the poet is needed too, the poet who is the wind of God to breathe life into the limp bodies there! And he neglects his duty if he is merely content, in however faultless fashion, to sing of the glory of bones.

And Australia, besides her own building operations, her own routine housekeeping work, her own joy in the fact of existence, and her own caution to ensure the continuance of that joy, has this big work for her poets to do, namely, to report, as Whitman would say, all things that have been and are elsewhere from an Australian point of view, both for her own benefit and guidance, and for the benefit of others.

The fact of evolution and the fact of Australia make Australian poets, if they will, essentially poets of the dawn — poets whose function is to chart the day and make it habitable — marching poets, working poets, poets for use, poets militant.

Some people tell you that the poet is functionless nowadays, that only in the dawn of the world had he a place and a message. It may be so, but in any case this is the dawn of a new world — a newer, stranger, vista widens before us, since Darwin’s great message reached us, than opened before Ossians of the Pleistocene, or Homers of the thawing glacial epoch. All, all is being thrown, has to be thrown, into the crucible of re-valuation, customs, morals, religions, laws, institutions, classes, castes, politics, philosophies — all, for at that apocalyptic word, “Evolution,” a new Jerusalem descended on the mental world, the old heavens and the old earth passed away, and it depends mostly, I contend, on the poet, the custodian of the innate prophetic wisdom of the world, the naturally sensitised plate for the reception of the intimations of the unseen Cosmos, it depends on him more than all whether a Millennium or a Pandemonium is to follow the pouring of the vial and the descent of the New City!

Don’t imagine I intend to imply that this world-work of the poet is being or to be done by the poets who happen to publish their poetry in books. They are only a few, not always the best, of the poetic host silently, obscurely, maintaining its poetic attitude to all people and things, singing its song, uttering the Word that shines in the Darkness though the Darkness comprehend it not. Indeed, published poets, by the fact of publication, show a trace of defect in their poetic constitutions, a trace of vanity as well as a trace of lack of faith in the innate power of their Word — that Word which, whether the world hear it with its physical ear or not, is never lost, and is just as much a worker of miracle! As the baby’s smiling but hardly audible “goo goo” teaches more of the secrets of the Kingdom that is Love to the leaning mother than all the theologies and sciences can, so does the unspoken poetry shining from the lives of those who feel the poetry in them and dare not suppress it, draw the dead world into orbits of living Love!

As opposed to the school, real life is a moving, changing thing, a current ever catching up the contents of the school billabongs and transforming them into new things. The school dare not teach more than the sum of the experience of the past: it supplies indeed a concentrated globule of the past to nourish that large part of us which is the past, but almost wholly worthless for the nutriment of that smaller but more important part of us which is the present, or that still smaller but godlike part of us which is the future.

The evil of the classical consists in this, that in some hands it is an attempt to put twentieth century wine into first century bottles. The classical, in so far as it is the summed up wisdom of the past, the wisdom of experience, is a heavy and hampering yoke on the shoulders of those, poets or artists or prophets, whose function in the world is to chart the wastes of the future. The work of such explorers is idealistic work, that is to say, they must have absolute freedom to soar or to dive where the Idea points; whereas the trend of the classical is towards rigidity, the beaten track, the precise, the crystalline.

But although I deprecate the undue intrusion of that classicalism which is the Law and Order of the Past in realms artistic, I would personally prefer to see each new age develop what I may call its own Classique, a lofty severe and effective Law and Order of its own, evolved not merely from the study of old masterpieces, but from the nature of the new themes with which it has to deal. In this sense, the Classical, that is the Reverent as opposed to the Random or Romantic, so far from being a burden, is a useful and even magical alpenstock to the climbing artist.

My personal view is that simplicity of form, extreme simplicity, besides being a cure for the wordy exuberance of the present day, is the best basis of a Classique suited to the needs of strenuous Australian verse-work. So far as such a Classique would tend to counteract the “sloppy” diathesis of much Australian literature, would compel the poet to cultivate his intellect as well as his emotions, and would, in a word, contribute the necessary Spartan element to the poetic commonweal, it is to be welcomed.

For my own purposes, for instance, I have thought that the fourteen syllabled line of Anglo-Saxon and early English poetry, long ousted from the position to which it was entitled by the intrusion of the more exotic transformed pentameter of the Court poets, just as the Saxon language was long ousted by the analogous intrusion of the French of the Court circles, is a peculiarly suitable one. The virtues of this wonderful line are only partly explored, principally because it has been held unfashionable by the rules of the Latin-Grammar School prosodies, as well as by the example of such great names, mainly suckled on Latin-Grammar School ideals however, as Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden and Pope. The praises, possibilities, and adaptabilities of this wonderful line have yet to be sung, but for my purposes herein I shall only say that it compels its user to confine himself to the matter in hand, it prunes undue tendency to mere ornamentalism, and it brings to the ears of its readers a chaste and lofty music, subtly low in pitch perhaps, but only so because it fittingly, that is to say, artistically, subordinates the call of the verbal music to the more important call of the thought-motif and the spiritual theme.

By the way, I want to mention here what I deem an unwarrantable heresy of the classicalism of last generation (a classicalism formulated by Coleridge and Wordsworth, and bolstered up past its legitimate life-epoch by Matthew Arnold and others, even in Australia, who ought to have known better!) That heresy is that Personification is not allowable in good poetry. When Personification had been abused by some followers of Pope, there was perhaps good reason to put a brake on the abuse. The veto was a severe but not unjustifiable dogma of the Classique necessary or useful for that generation. But the continuance of the veto into the present generation is an admirable example of how dangerous a yoke the Classical can be. For Personification, however, it may have been abused during a very insignificant period of English poetry, is, after all, the first right of the poet, the original tool of the poet. By it he created the gods and all their mythologies, the Virtues and all their graces; by it he whipped his vices out of the Sybarite, his hypocrisies out of the mediaeval Pecksniff and his avarice out of the universal miser; the dint of this great poetic welding hammer is more in evidence in a greater number of the strong verses ever smithied in any age or nation than the trace of any other poetic tool: in a word, by its magic more than by that of any other talisman, the poet has drawn the majority of human ideals from their wanderings in airy nothing, and given to them a local habitation and a name. Yet, forsooth, because Pope’s followers were not original enough to personify freshly, or to put blood and brains and vigorous vital organs into their personifications, we are, at command of their critics, to jettison for ever this most priceless cargo of the poetic barque, to repeal this most precious and most necessary clause of the Bill of Rights of the poet!

An important duty of the poet — and it is a singular comment on the poverty of modern poetry that one should have to say so at all and to insist on it — is that he should be original, that he should not merely echo, however beautifully, that he should explore the regions given him to explore, and return his own version of what he hears there. Form run mad has certainly resulted in the presentation of old material in original forms in Australia, but poetry of the continent is singularly barren in original idea, in traces of original thought. Indeed, Henry Lawson, one of the most reckless in regard to form, is the one of all who gives most evidence of original thought and fresh welling emotion. I am glad to notice, however, that in his latest book, “Egmont,” Hubert Church, the almost perfect New Zealand stylist, shows that he can think hard, fruitfully and nobly. With the new material available everywhere here, not only in Nature, but among masses of men loosened from old-world shackles, the lack of originality of thought in our poets is the more reprehensible. The poet must learn to know that it is not quantity that is asked of him, for a new message if but in one verse is more valuable to the people and more honourable to the poet than reams of verbal fluency or showers of pyrotechnics.

By the way — we have already a great poet in Australasia, but like the divine ancestors of Professor Spencer’s aboriginal Centralian tribes, he is split into fragments. In his complete form, he has the high seriousness, intimacy with nature and gentle recollections of rural England of James Hebblethwaite; the architectonic symbolism of Chris. Brennan, the rhythmic gramarye of Roderick Quinn; the epigrammatic acidity of Arthur Adams; the urbanity, culture and withal soupcon of an uncanniness suggestive of trespass on the astral, of Frank Morton; the cut-diamond brilliance and tonal quality of Hubert Church; the lyric splendour and organ-roll of Sydney Jephcott; the spontaneity and lilting lyric witchery of Jessie Mackay; the capacity for infinite toil and the elemental virility of Randolph Bedford and Grant Hervey; the vehement Australian outlook of these two and many others; the cantering raciness, colloquial fluency and popular appeal of “Banjo” Paterson and Edward Dyson; the clear and ringing rhyme of “Gilrooney,” Essex Evans, J. Sandes, E. J. Brady and Will Ogilvie; the incarnated Hellenic eye and ear of Hugh McCrae; the generous adieux to a dim and passing race of his veteran father, and his sister’s dainty maiden and mother meditations; the touchingly simple heart-notes, home-throbs of Mary Gilmore; the lucidly flowering dreaminess of Louise Mack; the rebellious singing lightning of Marie Pitt; the glinting optimism as of “runaway bits of sky” of Miss Baughan; the hot youth wrestling with exotic decadence of Rupert Atkinson; the passion for science of Johannes Anderson and Professor Osborne; the precision of epithet and bridled intensity of classical Archie Strong; the magpie warblings in the pines by the sea of Fred. Williamson; the sighing as of dying winds over acres of old-world tuberoses of Harold Pudney; the clarity of thought, brave outlook and verbal beauty of Frank Wilmot; the royal colouring of Arthur Bayldon’s splendid phrases; the epithalamion chastity of wedded form and thought of dainty Le Gay Brereton; and the radium that strains in the pitch-blendes of hot-hearted Henry Lawson. That meagrely outlined list will indicate, and only indicate, for there are many others, that there is at least prime poetic material in Australia now, capable of responding, with judicious mingling of powers, to any call a nascent nation could make on it.

There is one curse of the Classical, a curse because it tends to wither the sinews of originality, which I must mention, namely, the submission of the Present to the hypnotisation of the Past, and the consequent inability of the subject Present to rise in idea or method above the attainment of the Wizard Past. Although my own personal tendency is rather towards a reverent attitude to the muse, and a deep gratitude to the said Wizard for what he has done, I give in to no Random Romanticist in my protests against the doctrine that all the best poetry has already been written, or in my claims that every properly-dowered and properly trained poetic brain of to-day starts level with the most perfect achievements of the past, and is potentially capable of as great an advance upon that achievement as that achievement was in advance of the achievements of its Past. And I raise my protest and encourage my comrades, too, to raise their protests, in word, but preferably in deed, against subservience to the Past, against that too prevalent Orientalism which in art and literature kootoos, so abjectly that it becomes paralysed for its own great work, to the glory of the achievements — and the glamour that is more than the glory — of the truculent, narcotising and despotic past.

There is an aspect of the Psychology of the poet to which I must make a passing reference, because it appears to me that if I am right in the matter the average man is, though defect of the necessary experience, not very well fitted to judge the poet. Whether it be flattering to the prise of the individual poet or the reverse, there is very little doubt that his mental make-up has many analogies with that of those singular people, through whom the oracles of the Pagan world were delivered, or of whom we used to make bonfires in the Middle Ages when they wouldn’t sink to the bottom if thrown into a pond, or whom we put into gaol for preaching “subtle craft” when they gaze into a crystal and see the panorama of our fates unroll. No one who has had even spasmodic attacks of the fever poetic but, if observant and honest, will recognise numerous coincidences in his mental experiences at such times with those of such extra-normal persons as St. Teresa, the modern clairvoyants, the subjects of multiple personality, and the recorded cases of certain hysterics in the Paris hospitals. As some thinkers are rapidly coming to the conclusion that such extra-normal cases are, like cases of induced hypnotism, all explainable by the operations of what is known or postulated as the automatic, sub-conscious, sub-liminal or supra-liminal “self,” it may be that in this direction we shall yet gain more light as to the exact relationship, foreseen by the way by a poet, between the “lunatic, the lover and the poet.” Another point I want to make in this connection is that the poet seems to be in some sort, by his very nervous structure, sensitive to suggestions unfelt or unnoticed by his contemporaries; and his very instability senses motions on the pool of human mutation before their vibrations reach, or can reach, the average sensorium.

It is this psychological or nervous characteristic of the poet that particularly fits him for the exploration of the ultra-scientific, the so-called mystical or “occult” regions of human experience. He is more fitted for it than most of those who are called “sensitives” or “mediums,” for he does not usually labour, as most of them do, under the disadvantage of having a preconceived theory of the phenomena experienced. Besides, he can record his observations in that subtle imagery by which alone the elusiveness of absolutely new things can be fixed for human use.

A quasi-physiological point, too, deserves consideration, because it bears on my contention that it is the poet’s function in the world to work usefully for the progress of the species. It is, I am told, becoming clearer that there is more than a chance connection between high artistic power and the reproductive side of life — that is to say, that Love and Art are different branches, differently beautiful flowers, springing from and nourished by the same obscure root. My own way of expressing it is that what reproduction is in the physical world, representation (and all Art is representation!) is in the mental world. That is to say, the final cause of all Art is, by means of the selection and perpetuation of the beautiful, the Perfection of the species. If this doctrine be true, not only will it seem clear that the great poet’s work ought to be useful, uplifting, progressive, germinating, and that Beauty should on earth be at most only his lure, not his goal, but it will also enable such as desire so to do to find many well-founded excuses for a multitude of many a poet’s sins. Anyway, if the doctrine is true, poetry should not bloom merely for the sake of blooming, but for the sake of producing seed.

I am one who believes seriously, despite all the convincing evidences of common sense and common experience to the contrary, in the power of literature to lever the world into a more perfect orbit.

Of course many of you will think this is an exaggerated view of the importance of literature, but it is perhaps salutary sometimes to hear that there are people who believe in the greatness of their calling when that calling is looked upon very generally as one that helps to fill in the waste corners of a magazine, or to produce books useful as presents to sentimental friends, but never read by the donors.

Now, not only do I believe in the importance of the literary art as a world-moving force for good, but I think that this force is worthy the attention of practical people. For I contend, broadly, that the apathy which paralyses action so universally in these days, in politics, in religion, and in questions of social reform and the like, is largely due to the absence of the Poet from his place in these spheres of reforming action. We cannot push on a Cause, however we may be intellectually convinced of its rightness, and however we may be theoretically interested in it, unless we also vehemently desire its success, vehemently wish that its principles be adopted by the world.

For, in a high sense, the Universe is and will be what man wishes it to be, that is to say, really wishes it to be. For it is not sufficiently recognised that we are plagued all through life by half-wishes quarter-wishes, wishes that we think our own but which are really other people’s, and wishes that our full selves secretly pray may never be realised. What a man as a whole clearly and calmly and deliberately wishes usually bears fruit. The almost universal civilised wishes about the abolition of torture and of slavery, about toleration, about the alleviation of the unnecessary horrors of war, about the care of the helpless, about a thousand other things, are coming to pass under our eyes, and similarly our present day real wishes are a forecast of the better world of the future. There is at least this truth in the Pragmatist position in philosophy that the future of the world shall be very much what we now really desire it to be. And who, forsooth, is the best wisher, the best desirer, the clearest expresser of his and our wishes and desires, but he who most intensely believes in his wishes, his desires, who almost supernaturally believes in them, namely, the Poet? Were it only for the fact that he can teach us how to wish, the poet is one of the most valuable human assets.

The personal duty of the poet, apart from the acquirement of the technique requisite for his themes and appropriate thereto, is a very difficult one to fulfil. He has to labour painfully in the acquirement of knowledge, to resist the hardening influences around him which would make him less sensitive to the human cries we too frequently succeed in shutting out, and to the more than human whispers vibrated through plants and flowers and birds and stones and human symbolism by Operators at the Other End. He has to wrestle with his Reason even, when it would sally beyond its appointed domain. He has to be courageous, in the face of adverse opinion, his own interest, his friend’s wishes, to utter his message whomever it displease, whatever it threaten to destroy, however its utterance may affect him or his, including his reputation and his very title to poet. He must absorb his country, his time, his environment. He must learn the difficult lesson of love — for Poetry Militant is not the poetry of hate — love, the true solvent of all human evil, and peculiarly necessary to him, as a fighter against, not men, his brother, but against the embodied and often evil powers of the Past which use men as their pawns, and which we know as institutions, or flatter by calling “Laws of Nature.” He must so live his personal life that nothing he does in his poetic life is done against his conscience, whether it be in consonance with other people’s consciences or not. It is doubtful whether ever a true poet, however he may shock our consciences, ever could have uttered poetry if in it he ignored the command of his own conscience. In that fact, for I think it is a fact, lies probably the real link between the Good and the Beautiful, the link that makes them one. I think that most of us who have tried to write poetry have felt, perhaps dimly, that all that stood between us and our highest possible performance, has been our failure to act up to our highest lights in our ordinary lives. Many a time will we see in after years the trace of moral imperfection, cowardice, anger, unkindness, intolerance or other succumbing to temptation, in the blemish which mars for ever an otherwise perfect verse. This strange sensing of a connection between the Moral Idea of the universe and the Ineffable Beauty of the universe is a privilege of the poet, which makes his calling sacred to him, and which gives him a faith in the real existence of Perfection and its ultimate attainment by all, which no mere reasoning and no science of the mere phenomena of life can shake. That is why, too, probably, no great poem is intentionally written for a bad purpose — indeed such a poem could not be written, for the Powers of Evil are the very opposite of the Poetic Powers, that is the creative good Powers of the Universe.

Among the poet’s duties are visits to the Wells of Rejuvenescence, for he is a citizen of the Land of the Ever Young (Fairyland, some call it!), and to maintain his citizenship must drink of its springs. Fortunately, for the right eyes these springs abound, in the eyes of babies, in the inner whorls of canna lily leaves, in the winter wattles, the foal in the paddock, the gambols of six year old boys, amid the warm roses that cluster round great, unselfish Causes, in the aisles of cathedrals sometimes, and in fervour of Bethels, but most of all in the love of home-folk, comrades and — lovers!

Although it is one of a poet’s functions to please, especially in an age of drab pleasures, he has other and more important ones. I shall refer to a few of them.

The ineffable Beauty hovering over and permeating the world gives hints of its existence in those passing mirrors we call beautiful sounds, thoughts, things and people. Man thirsts for it, perhaps, as Plato hints, from an innate recollection. The poet’s function is to quench this thirst. He does this by listening to the oracles which the mirrors are, and when he has understood, re-presenting to us who are waiting, their answers in the only right words, and with those vibrations, analogous to the vibrations of the universe, which we call rhythms; he is, in fact, a gatherer of the scattered dew-drops of Everlasting Beauty.

But that, though his most delightful task, and indeed his main function when Poetry becomes triumphant, may be a hampering one if unreasonably pursued during the stage of Poetry Militant.

In such a stage, men need gods, and new men new gods to drag them onward and upward. That is to say, we need embodied principles of action better than our average selves to lead us out of our average selves on to the realisation of higher selves. The poet’s function is to create gods, and in every age of human progress the poet has been the most authentic and effective creator of gods and of the mythologies that give them bone and blood and power.

He may also have to destroy gods when their hour strikes. Or, to put it another way, the poet’s duty is also to unveil “frauds.” I do not mean by this to confine to the Scotland Yard of Satire worthy as the example of Aristophanes, Horace, Juvenal and Pope shows that work to be, and badly as it is needed in our own dark corners. The poet’s more important duty in this respect is the detection and unveiling of frauds that conceal him from himself, us from ourselves, the frauds we hug sometimes for centuries, the frauds we disguise under names of divinities, the darling frauds that make life very comfortable, but its air very stuffy. Such frauds are so subtle that we sometimes build codes of morality upon them, and buttress throne, laws and religions by means of them; yea, nations have accepted them, have risen, flowered and fallen without knowing that they were frauds at all. They are very dangerous foes to face, for all men side with them, even the poet himself by hereditary predisposition as well as by the acquiescent toleration of habit, and woe to him who taps their statues in daylight and reveals the feet of clay! Every artist, every poet, every genuine reformer knows what I mean, although if I mentioned a name, he would protest with the rest, for our language is so infected with the glamour-producing vocabularies of the frauds we adore, that the mention of names even would seem blasphemy, immorality.

Another of his functions is the co-ordination of Truth and Goodness with Beauty. It is just as big an artistic heresy to say that Art is for Beauty alone as to say that it is for Good alone, or for Truth alone. Art is for The Good and The True by the way of the Beautiful. Conduct is for The True and The Beautiful by the way of The Good. Science or Philosophy is for The Good and The Beautiful by the way of The True. It is only in the school that any of these three faces of the Infinite Unity is to be gazed at for Its own sake. Thus you will see that Art has its Athanasian creed as well as its only too popular Arian heresy!

It is not enough, however, that Poetry Militant should be useful and beautiful; it must also be interesting. To deal in an interesting manner with matters interesting to his age has indeed ever been, whatever other qualities are also demanded a sine qua non of the great poet. Though a truism, it is necessary to repeat it, for too many men of great poetic capacity in our time persist in refusing to deal with great subjects in which the people are intensely interested. We have scarcely any great political poems nowadays, although everyone is interested in politics, and although politics in Australia have the potentialities of a demigod if rightly evoked. We have scarcely any great religious poems, devotional poems either. Kipling’s “Recessional,” which atones for a multitude of his sins in the eyes of many of us, and “Lead, Kindly Light!” are oases that reproach the stylist, who would condemn them as useful, for the modern deserts of devotion. (Yet the power of such poems is enormous, magical. Indeed, if you will excuse a personal note, Cardinal Newman’s hymn, Professor Denton’s rationalistic “Be Thyself,” and a fragment of a hymn beginning “Dare to be a Daniel, Dare to stand alone!”, which I heard over 20 years ago, while passing a Ballarat street preacher’s meeting, have been as the whole seven gifts of the Holy Spirit to me in my own pilgrimages thus far!)

The neglect of the fairylands of Science, the richest peculiar dowry the modern world has received, by the modern poet, again at the bidding of the old-time critics, is one of the disgraces of the age. For Science, intended for all, speaks to a very narrow, and often narrow-minded audience, because the Poet, fearing the label “didactic,” a bluff-word of the old school of critics, will not illumine and humanise it with his poetry.

As to songs of the relations of the sexes, most poets stop at the commonplaces of traditional sentimentalism, and the staging of unreal thoughts and unfelt feelings. There is, certainly, an unhealthy school with the watermark of conventionally allowable decadence, and the smell of the grave, on its spoiled paper. But the subject is so generally banned that even the honest, holy, and sweet Song of Solomon would have short shrift with the modern bookseller, but that he can sneak it out to customers between the leaves of unimpeachably proper proverbs and prophecies. Yet the Song of Sex has got to be sung, reverently sung, for the problems of sex being part of the mystery of creation are perhaps the most interesting of all to every truly normal individual, on the solution of some of them probably depends the fate of civilisation, and no one, not even the scientific man or the moral philosopher, can probe them with such delicate lancets, or flood their hot darkness with such cool and clarifying light as the poet with his reverence, his sympathy and his second sight, can. Moreover, it is in this region that the poet can best demonstrate, what theologian or moralist has never done there, that the True, the Good and the Beautiful are One!

Scarcely a poet exists but has his illuminating answers on the many phases of this question, answers which, while they may not be the whole truth, are important pointers towards the truth, yet scarcely one, save with bated breath, dare say a word of what he yearns to say. There, if anywhere, the poet can create gods, pure, sweet, beneficent gods who can clear away the age-old putrefactions with which the sacred name of sex has been encumbered and polluted, and who can lead men and women, under the sweet sane daylight that sex has never yet seen, to Edens, millennia, upward and on! The world does not yet fully know, as it shall know, its deep debt of gratitude to the courage of poets like Walt Whitman, Henrik Ibsen, and splendid old John Davidson for their noble pioneering work in this great America. After all, are not those three among the first in the world who really saw the misty outlines of that fabled land of the West, about which the Celtic bards were so fond of singing, and Henry Kendall too dimly sighted here in Australia — Hy-Brasil, surely the land of perfect men and women perfectly mated?

As to Social Reform, which is the attempt to extend the doctrine of the Golden Rule from our relations to one another as individuals to our broader social relations and responsibilities, there is no subject in which the present age is more interested, yet there is scarcely a subject that is more neglected by the modern poets (admitting important exceptions, of course), and certainly scarcely a subject favoured by them that is as worthy of treatment. I do not want to repeat here what I have said over and over again elsewhere in prose and verse about the duty of the poet, in this age of combat against all that holds down one least human soul, to take his full share, and as a poet, in this great war, where Love is the principal and most effective form of artillery. So I shall content myself with this allusion to it, and a quotation from Francis Adams, himself elsewhere an almost squeamish purist in art, in his song on “Art.” He said:—

Yes, let Art go, if it must be

That with it men must starve —

If Music, Painting, Poetry

Spring from the wasted hearth.* * * * *

Nay, brothers, sing us battle songs

With clear and ringing rhyme;

Nay, show the world its hateful wrongs,

And bring the better time!

I do not think I am going too far when I say that the majority of modern critics and of the abler contemporary verse-writers rigorously taboo politics, religion, sex, social reform and science from poetical treatment, although somewhat illogically, but constrained no doubt by the weight of precedent, they allow War and Sport admittance into the funny charmed circle of the arena of poetic.

Now, I contend that Politics, Religion, Sex, Science and Social Reform, being some of the principal subjects on which modern men and women are most genuinely interested, are therefore worthy subjects of great poetry. I submit, too, that although subjects interestingly real to one age are not necessarily interesting or real to a different age (for even Reality is relative in this Passing Show of ours), the history of great literature bears out my contention that the great poetry of the world has been written on subjects in which the people of the poet’s time were intensely interested, and that it was mostly written with some great purpose clearly visible or thinly disguised. This is, after all, another way of saying that the great Poetry of the world is mainly and deliberately Poetry Militant. Let us look at a few instances.

When raiding and war, and their real or mythical ancestors were vividly interesting to men, and when knowledge of these matters was of great public importance, their great poets gave them Iliads, Odysseys, Sagas, and Nibelung Songs.

When the Greeks talked or fought all day and dreamt all night about religion, philosophy and politics, their great dramatists illuminated religion and philosophy, now with the lightning of Aeschylus, now with the noon-day light of orthodox Sophocles, now with the Greek fire and relentless searchlights of agnostic, iconoclastic and strangely modern Euripides; while the St. Elmo fires of humour or the radium-like satire of reactionary Aristophanes glinted along the spars of every Utopian ship, or played on the lupus of political humbug that scarred his doomed contemporaries. Sport, too, reigned over so many Greek minds that Pindar, seizing their interest in it, built of it his immortality.

When Romans were interested in Stoics and Epicureans, in the supernaturalism and rationalism of their times, Lucretius made out of their interest and his own brave big poetic soul his mighty book, with a purpose on every page.

When they were interested in their newly acquired imperial glory, and wanted a stately pedigree thereof to cool the shame for their lost liberty, another great poet deliberately wrote one of the greatest poems of the world for that purpose.

When the conquering Aryans of India, equally interested in war and their mythologies, stimulated their poets to do their duty, the sublime panorama of the Mahabharata unrolled; and, moreover, to delight and inspire and help the good man of every land for ever, secreted in its mighty folds, appeared the Bhagavad Gita, the Song Celestial, that “Sermon on the Mount” of the Orient, perfect in form, jewelled in phrase of the purest poetical water, and yet a complete treatise on morality and duty, and a sublime justification of the ways of God to man!

When in the Italy of the city states men’s interests were in Catholic theology, and, to bloodshed point, in bitter party politics, tempered by the tendency of the time to dream of ideal loves, of what did its great poet sing? Why, of hell, purgatory, and heaven, Beatrice, Aristotle’s philosophy suitably Bowdlerised, and curious astronomies, and of the Mr. Deakin of the period fusing in Purgatory, the Mr. Fisher assessing the unimproved value of the Elysian fields in Paradise, and Mr. Someone Else cooking in the cauldrons or lost in the forests of the Inferno, almost exactly where the partisans of Dante’s particular political colour vehemently wanted them to be. In a word, Dante dealt in an interesting manner with matters absorbingly interesting to his period, and accordingly, being also a poet, he was the greatest poet of that age, so great that he is interesting yet.

Elizabethan England, interested in the great new worlds opened by the Renaissance and by Columbus, interested in magnificence, in spectacles, in the glories of England and of Elizabeth, gave us the spacious stage of Shakespeare, the Fairy Queen of Spenser, and the lesser glories, each a star in its own right. But the gentleman with an axe walked abroad so frequently those days, as you remember, that even poets dared not write much of politics or of religion. Unfortunately, the example of Shakespeare and the others, forced on them by the stern necessities of the time, has been the chief argument for those who contend to-day that poetry is no place for either religion or politics, that they are hardly fit staple for poetry at all. Fortunately Milton didn’t think so, or he could never have written the epic of that theology in which Puritan England was so interested that it killed a king and built a commonwealth to commemorate its interest.

And so with Faust — philosophy, theology, science, mysticism, ethics, Hellenism — all, in fact, that the German Illumination stood for, all that awakening Germany was vitally interested in, are embodied in that great poem of her greatest poet.

I contend, therefore that, as in the past the great poet has been the illuminating Answerer of the great and interesting questions of his day, whenever there were such great questions, or whenever any man dared to answer them, so must the poet of our age, to fill his part as a social artillerist, answer the great and really interesting questions of our day.

“Why should poetry be militant nowadays?” I hear some ask. Because, in the first place, this is an age of Revolt and of Reconstruction, because the Poet is the father and mother of wise rebellion, and because he, being in touch with the Infinite, the Permanent, is the most potent and far-seeing stimulator of reconstruction. He is Brahma the Creator and Siva the Destroyer in one, and this is not so much the Age of Vishnu the Preserver, as it is the age of Destroying Siva and re-creating Brahma.

Partly through the readjustments necessary everywhere in religion, politics, ethics, as well as in thought generally, on account of the advent of evolution doctrines; partly on account of the spread of education and of a little justice to the masses, as a result of the world-movement of which the French Revolution was, and the Turkish revolution is, a symptom; and partly on account of the failure of old ideals and teachers to guide, owing to the operation of the factors just mentioned; the world of thought, of conduct, and of action is in a state of chaos, out of which man can, I contend, only be permanently led by his naturally endowed teacher, jurist, philosopher and theologian, the poet. For originally the poet is all these, and through all time, however the principle of the division of labour may have affected his work, has potentially been all of these, besides being poet pure and simple. And when, for any reason, these fail in their functions, the race depends on the still surviving matrix of them all, the poetic quality or capacity, to evolve a new race, suited to the new conditions, a new race of teachers, jurists, philosophers and theologians. Indeed it is from a strong belief in the essential truth of this position that I hold two men, one of whom would be denied right to the name of poet by millions, and the other of whom would be denied that right almost unanimously, to be the two greatest poets of this age of the Evolution Dawn. Those two poets, Destroys and Creators, are Walt. Whitman and Frederick Nietzsche. If you want a third, I do not object to add the author of Brand, yea, if you like, and will forgive my want of logic, the sublime symphonist of the “Legend of the Ages”; and one who, by some strange miscarriage of the Earth-Spirit, was yeaned a century before his due time, William Blake! But that’s a digression! Poetry should be militant nowadays, because the call of the growing new world is to battle. Foes to the progress of the species are alert to-day, and subtly active, too, to a most dangerous extent. Democracy, the surely destined ruler of the near future, is upon us, an infant king, untaught as yet in the duties of kingship. Prosperity in his train, prosperity with glowing eyes, but deaf, deaf ears, beckons her myriads to callous revelry, faded garlands and suicide. Wealth accumulates, wastes, tyrannises, corrupts, degrades, and, worst of all, forces his grovelling gods into the altars of the cleaner divinities we once adored, substitutes his base commandments for the Decalogues our apathy repeals. Old castes may be disappearing, but coteries of the intellectually proud, the spiritually proud, the artistically proud, segregate themselves from the intellectually, spiritually, artistically hungry and thirsty masses of the people to whom they belong, and threaten to form a caste-system more subtly odious than ever, where the prevailing characteristics shall not be the physical luxury and physical starvation of the previous epochs, but intellectual, artistic and spiritual starvation among the masses, and among the new castes of intellectual, artistic and spiritual gluttony.

Why should poetry be militant nowadays? Look around you in your cities of vapid pleasures, and of eructations of mob emotionalism, now for prize fighting, now for anti-gambling, now for the religion of the God of war, now for the religion of the God of peace; where a myriad envies, and what Carlyle called preternatural suspicion, affects like a gangrene the body of the rising working classes; and where our fearful complacency tolerates the existence of the square miles of foul rookeries where the children that are to be our future nation are being devitalised, and where their mothers are living with wonderful courage their drab and painful lives! Look around you in your country districts, where intellect, lofty emotion, the vigour of youth, the promise of childhood — everything — are being sacrificed daily to the cult of the cow, the usury of the mortgagee, the lure of the bank-balance, the avarice of the eater of acres! Look around you at so many of your newspapers, the only universal guides and consciences of your people, yet framing their ideals of what is fitting and proper, in ethics as in politics, in taste and in culture, upon, not the highest that is in their writers, or even their owners, but upon the bad average of the biggest mob’s envy, half-cooked sentimentalism, and materialistic ignorance. So with too many of your preachers, your politicians, even with too many of the very few of them that know any better.

Everywhere it is the mob that rules, the rich mob, the poor mob, the bell-toppered mob, the ragged mob, the rude mob, the cultured mob, but always the insensate, the complacent, the selfish, the unethical mob, and the mob is the danger-spot in Democracy’s lungs! Surely, if ever there were a time when the poet should fight, the poet who is essentially one who dare face any mob, whose greatest function is to turn a mob into a people, to exorcise the mob-spirit out of the people; surely, I say, if ever there were a time when poetry should be militant, relentlessly militant, it is now when, failing a remedy, Democracy may have to turn again to despotism for aid to rescue her from the soulless materialism and hysteric passions of the mob that afflict her!

My call in what I have said herein and elsewhere is to the poets hidden among the people, the young and appointed saviours of the people, to come out into the open with the other soldiers of reform, social and spiritual reform, and to play their parts, using the peculiar ordnance of their corps, to make this our country in every way fit to live in, worth dying for. I know they have technical power which any people’s poets might envy, but I see evidences of lack of knowledge, of disinclination to do the hard preliminary work necessary for the poet’s equipment, and of a tendency to waste their power on mere prettiness, mere payable poetry. They can do more than any to plant civic unselfishness, to encourage the “forward view,” and to fan that zeal for nothing less than the best and most just which must burn in the people before they can fully earn the right to the root-and-branch social reforms necessary enough; and they can do more than even the clergy, I think, if they have a mind, to keep burning that love in the heart of the people without which the harvest of the gospel of social reform would be choked with strife, hate, envy and all uncharitableness. Indeed, to the silent influence of good poetry for permanent good, there are absolutely no bounds. It is the true nation-maker; yea, mayhap, at the Last Day, the nations shall be judged by the poets they have produced!

And I do not call for the mere sake of calling, but because Australia has specific work for them to do, namely, to take their sides for or against the causes of Progress or Inertia, according to their knowledge; to build soundly every storey of this great Australia or to shatter what is built and erect more wisely, by their poetry; to make, in a word, of poetry a renewing social force or a preserving social force, the generator of the new Dynamic, or the reservoir of the old Inertia, which religion was once in turns in most countries, but can no longer be, which war and conquest were often in the awful past, but which, let us hope, they need no longer be.

To answer my call, which, after all, is but the voicing of the clear enough call of our age and country, will mean self-sacrifice, perhaps poverty, perhaps obloquy, certainly loneliness, misunderstandings, discomfort, hard work, ingratitude, and little or no visible result, perhaps, in a lifetime! But in the halls of the Spirit, too, the same call is being made, and they of the Spirit shall hear it, and it is the law of the Spirit that, reward or no reward, he who hears its call is by the fact of hearing put on his honour to answer it. And the disciples of the Spirit must ungrudgingly leave the pleasant studios where the glories of Form seem a visible translation of the harmony of the spheres, the studios where they had been sent to school, to see, at the beginning of their pilgrimage, adumbrations of the perfect forms that shall welcome them at its triumphant ending — yea, they must leave those studios for the Pilgrimage Militant — leave all, friends, home, dear delights, dear beliefs, leave all and follow — the Spirit.

I cannot better conclude this plea for the formative poet, and for poetry militant, than by quoting a passage, which, but for my own deficiencies, would summarise my case, from Walt Whitman’s “The Answer” —

The words of the true poems give you more than poems,

They give you to form for yourself poems, religions, politics, war, peace, behaviour, histories, essays, daily life, and everything else.

They balance ranks, colours, races, creeds, and the sexes,

They do not seek beauty, they are sought,

Forever touching them, or close upon them follows beauty, longing, fain, love-sick.They prepare for death, yet are they not the finish, but rather the outset;

They bring none to his or her terminus, or to be content and full;

Whom they take, they take into space, to behold the births of stars, to learn one of the meanings,

To launch off with absolute faith, to sweep through the ceaseless rings, and never be quiet again.

The substance of this Book was delivered as the Presidential Address of the Literature Society of Melbourne, 1909, and is now republished with revisions and additions

Specialty Press,

Art Printers,

189 Little Collins St., Melbourne

Source:

Bernard O’Dowd, Poetry Militant: An Australian Plea for the Poetry of Purpose, Melbourne:

T. C. Lothian, 1909

[Editor: Corrected “epithalamian” to “epithalamion”.]

Leave a Reply