[Editor: This is a chapter from The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers (5th edition, 1946) by J. J. Kenneally.]

CHAPTER XVI.

SHERRITT EXECUTED.

The Kellys were in no way harassed by the policy pursued by Supt. Nicolson, and as long as the police kept out of their way no one in the district was hurt. It was the general belief that the Kellys had left the North-Eastern district. Even Sergeant Steele was under that impression. On his oath on May 31, 1881, Sergeant Steele said, “I was under the impression that they had left the district altogether.”

Aaron Sherritt expected trouble after his quarrel with Mrs. Byrne and his threat to shoot and outrage Joe Byrne. Supt. Hare decided to take ample steps to protect this spy, and sent four policemen to protect Sherritt by day and night. The four policemen who were to protect Sherritt were Constables Armstrong, Alexander, Duross and Dowling.

These four constables stayed with Sherritt and his wife all day, and Sherritt used to accompany them at night to watch Mrs. Byrne’s home. The avowed object of this watch was to come into contact with the wanted Joe Byrne. It was thought by Supt. Hare that if only these four strapping young constables could get near the outlaws there would be something doing — something out of the ordinary. The constables were armed to the teeth, and were selected for this special duty so that they might retrieve the somewhat besmirched reputation of the Victorian police force.

The Outlawry Act lapsed with the dissolution of the Berry Parliament on February 9, 1880. Now that there was no “Outlawry Act” the two Kellys stood before the law just the same as any other men for whose arrest warrants had been issued. But the case of Joe Byrne and Steve Hart was different. The only warrants issued for their arrest were contained in the “Outlawry Act,” and now that that Act had lapsed there was not even a warrant in existence for their arrest.

THE OUTLAWRY ACT.

ANNO QUADRAGESIMO SECUNDO.

VICTORIAE REGINAE.An Act to facilitate the taking or apprehending of persons charged with certain felonies and the punishment of those by whom they are harboured.

Whereas of late divers persons charged with murder and other capital felonies availing themselves unduly of the protection afforded by law to accused persons before conviction and being harboured by evil-minded persons remain at large notwithstanding all available attempts to apprehend them and some of them being mounted armed and associated together have committed murders and have resisted and killed officers of justice whereby the lives and property of Her Majesty’s subjects are in jeopardy and need better protection by law: Be it therefore enacted by the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly of Victoria in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same as follows (that is to say):

1. This Act shall be cited as the “FELONS APPREHENSION ACT 1878” and shall apply to all crimes committed and evidence taken and warrants issued and informations laid relating thereto as well before as after the passing of this Act.

2. Whenever after information made on oath before a justice of the peace and a warrant thereupon issued charging any person therein named or described with the commission of a felony punishable by law with death any judge of the Supreme Court on any application in chambers on behalf of the Attorney-General and upon being satisfied by affidavit of these facts and that the person charged is at large and will probably resist all attempts by the ordinary legal means to apprehend him may forthwith issue a bench warrant under the hand and seal of such judge for the apprehension of the person so charged in order to his answering and taking his trial and such judge may thereupon either immediately or at any time afterwards before the apprehension or surrender or after any escape from custody of the person so charged order a summons to be inserted in the “Gazette” requiring such person to surrender himself on or before a day and at a place specified to abide his trial for the crime of which he so stands accused. Provided that the judge shall further direct the publication of such summons at such places and in such newspapers and generally in such manner and form as shall appear to him to best calculated to bring such summons to the knowledge of the accused.

3. If the person so charged shall not surrender himself for trial pursuant to such summons or shall not be apprehended or being apprehended or having surrendered shall escape so that he shall not be in custody on the day specified in such summons he shall upon proof thereof by affidavit to the satisfaction of any judge of the Supreme Court and of the due publication of the summons be deemed outlawed and shall and may thereupon be adjudged and declared to be an outlaw accordingly by such judge by a declaration to that effect under his hand filed in the said Court of Record. And if after proclamation by the Governor with the advice of the Executive Council of the fact as such adjudication shall have been published in the “Government Gazette” and in one or more Melbourne and one or more country newspapers such outlaw shall afterwards be found at large armed or there being reasonable ground to believe that he is armed it shall be lawful for any of Her Majesty’s subjects whether a constable or not and without being accountable for the using of any deadly weapon in aid of such apprehension whether its use be preceded by a demand of surrender or not to apprehend or take such outlaw dead or alive.

4. The proclamation as published in the “Government Gazette” shall be evidence of the person named or described therein being and having been duly adjudged an outlaw for the purposes of this Act and the judge’s summons as so published shall in like manner be evidence of the truth of the several matters stated therein.

5. If after such proclamation any person shall voluntarily and knowingly harbour conceal or receive or give any aid shelter or sustenance to such outlaw or provide him with firearms or any other weapon or with ammunition or any horse equipment or other assistance directly or indirectly give or cause to be given to him or any of his accomplices information tending or with intent to facilitate the commission by him of further crime or to enable him to escape from justice or shall withhold information or give false information concerning such outlaw from or to any officer of the police or constable in quest of such outlaw the person such offending shall be guilty of felony and being thereof convicted shall be liable to imprisonment with or without hard labour for such period not exceeding fifteen years as the court shall determine and no allegation or proof by the party so offending that he was at the time under compulsion shall be deemed a defence unless he shall as soon as possible afterwards have gone before a justice of the peace or some officer of the police force and then to the best of his ability given full information respecting such outlaw and made a declaration on oath voluntarily and fully of the facts connected with such compulsion.

6. In any presentment under the last preceding section it shall be sufficient to describe the offence in the words of the said section and to allege that the person in respect of whom or whose accomplice such offence was committed was an outlaw within the meaning of this Act without alleging by what means or in what particular manner the person on trial harboured or aided or gave arms sustenance or information to the outlaw or what in particular was the aid sustenance shelter equipment information or other manner in question.

7. Any justice of the peace or officer of the police force having reasonable cause to suspect that an outlaw or accused person summoned under the provisions of this Act is concealed or harboured in or on any dwelling-house or premises may alone or accompanied by any persons acting in his aid and either by day or by night demand admission into and refused admission may break and enter such dwelling-house or premises and therein apprehend every person whom he shall have reasonable ground for believing to be such outlaw or accused person and may thereupon seize all arms found in or on such house or premises and also apprehend all persons found in or about the same whom such justice or officer shall have reasonable ground for believing to have concealed harboured or otherwise succoured or assisted such outlaw or accused person. And all persons and arms so apprehended and seized shall be forthwith taken before some convenient justice of the peace to be further dealt with and disposed of according to law.

8. It shall be lawful after any such proclamation as aforesaid for any police officer or constable in the pursuit of any such outlaw in the name of Her Majesty to demand and take and use any horses not being in actual employment on the roads arms saddles forage sustenance equipments or ammunition required for the purposes of such pursuit. And if the owner of such property shall not agree as to the amount of compensation to be made for the use of such property then the amount of such compensation shall be determined in the Supreme Court according to the amount claimed in an action to be brought by the claimant against Her Majesty under the provisions of “THE CROWN REMEDIES AND LIABILITIES STATUTES 1865.”

9. No conveyance or transfer of land or goods by any such outlaw or accused person after the issue of such warrant for his apprehension and before his conviction if he shall be convicted shall be any effect whatever.

10. THIS ACT SHALL CONTINUE IN FORCE UNTIL THE END OF THE NEXT SESSION OF PARLIAMENT.

By Authority: John Ferres, Government Printer, Melbourne.

The Berry Government passed the above Act on November 1, 1878, and the end of the next session of Parliament was 9/2/1880, when Parliament was dissolved. Therefore there was no Outlawry Act after February 9, 1880.

* * * * *

Dan Kelly and Joe Byrne left Greta on Friday night to go to Sherritt’s at Sebastopol. They knew that Sherritt had police protection, and knew the risk they were running in meeting superior numbers. But somehow the Kellys had formed a very low estimate of the courage and fighting qualities of the police. Ned Kelly estimated that one Kelly equalled forty policemen. In the opinion of the Kellys, the attitude of the police changed from savage cruelty to arrant cowardice. Dan and Joe took up their position in the ranges close by, and remained there all day Saturday, June 26, 1880.

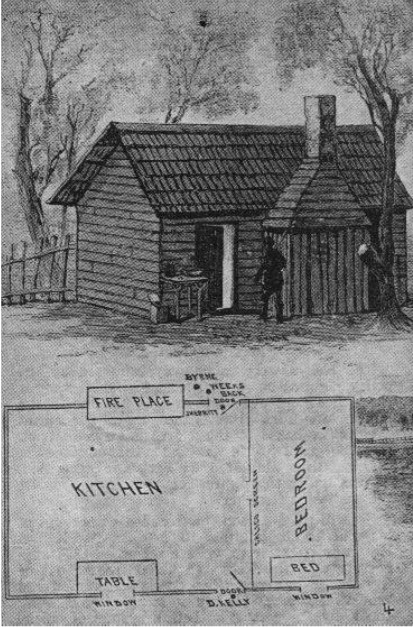

They had tea early, and, as darkness set in, they came down and tied their horses up at a convenient distance from Sherritt’s house; they also had a pack horse carrying their armour. As they issued forth they came across a German named Anton Weekes. They handcuffed Weekes, and told him as long as he obeyed their instructions he would not be hurt; but if he refused then they would deal with him in a most drastic fashion. Weekes said he would do what they wanted, but he could not do much. Joe Byrne told Weekes to go up to Sherritt’s house, knock at the back door, and say that he had lost his way, and ask Aaron Sherritt to show him the way to his hut. Weekes readily agreed, and was somewhat surprised at the simplicity of the task imposed on him. He went up to Sherritt’s, but never suspected that Joe Byrne intended to do something to Sherritt. He and Joe Byrne went to the back door, and Dan Kelly went to the front door. The house was a two-roomed wooden slab building with kitchen and bedroom only. Weekes knocked at the back door, and Joe Byrne stood a little distance from him. They heard a shuffling of feet inside and Aaron Sherritt called out, “Who is there?” Weekes said, “It’s me, I loss my vay.” Mrs. Aaron Sherritt came to the door, and opening it said, “It’s Anton Weekes; he has lost his way.” Aaron Sherritt then came to the door, the light fell on Anton Weekes, and Joe Byrne stood close by in the darkness. Aaron Sherritt in a joking way said, “Do you see that tall sapling over there?” As he uttered these words Aaron shrank back a little as if surprised at what he saw. Just then Joe Byrne fired, and stepping quickly into the room fired a second shot, and Sherritt fell and died without uttering a word.

When Weekes first knocked at the door Constable Duross was in the kitchen with Aaron Sherritt, his wife, and his wife’s mother, Mrs. Barry, who had arrived about fifteen minutes before Weekes. Duross immediately went to join the other constables in the bedroom. That was the shuffling of feet that Joe Byrne had heard. The four constables were very much scared by the report of Joe Byrne’s gun so close at hand. They were all armed, but were very much afraid of getting hurt.

Aaron Sherritt’s mother in law — Mrs. Ellen Barry — giving evidence before the Royal Commission on July 20, 1881, said:— “I was just about a quarter of an hour inside when a knock came to the door, and Aaron asked who was there. His wife asked who was there first, and the German answered, and she said, ‘It is Anton Weekes; he has lost his way.’ Aaron went to the door, and Weekes said, ‘Come and show me the way; I have lost my way.’ Aaron opened the door and I went to the door with him, and he mentioned a sapling as he was going out, but that was out of a joke. I went with him just to the door behind him. I heard Aaron say, ‘Who is that?’ and as he said the words he seemed as if inclined to come in again. He just had that word out of his mouth when a shot went. I just stood on one side of Aaron and stepped backwards into the middle of the room, and there was another shot fired through the door, and my daughter was standing just behind the door, and the shot passed her face, and she went back into the bedroom. Aaron stood on the middle of the floor and I was looking at him, and could see no mark on his face, and I heard no noise. I turned round, and there was a man standing with his back to the door, and he fired a second shot at Aaron, and he fell on the floor. He never spoke, not a word. I did not know at the time who fired the shot. He (Aaron) stumbled some time before he fell, and then he fell backwards. I went and stooped down, and knelt down just by his head, and I could see that he was dying. This man (Joe Byrne) called me by my name, and he said he would put a ball through me and my daughter if we would not tell who was in the room. Duross was in the sitting room when the knock came to the door, and he walked into the bedroom then, and I was thinking he might have heard the man’s step going into the room, as he asked who was the man that went into the bedroom. I asked Byrne would he let me go outside. He gave me orders to open the front door directly after that, and as I did I saw another man in front of the door with a gun. Byrne was at the back door, and this other man at the front. I asked him (Byrne) to let me outside, and he said, ‘All right.’ So when I went outside I saw Weekes standing by the side of the chimney. He was handcuffed, but I could not see at the time, it was too dark; but I could see Byrne taking them off. Byrne said to me outside, “I am satisfied now, I wanted that fellow’ — that was Aaron. ‘Well, Joe,’ I said, ‘I never heard Aaron say anything against you.’ And he said, ‘He would do me harm if he could; he did his best.’ He (Byrne) told me to go in and bring the man out of the bedroom, for my daughter had told him it was a working man looking for work, and said his name was Duross. I went into the bedroom and told the police to come out. They were looking for their firearms. When I went in the room was dark; in fact, it would be very hard to know what they were doing; they were stooping looking for firearms, and beckoned me to go outside. They did not want to make a noise. The police could have shot Joe Byrne when he stepped inside to fire the second shot if they had their firearms ready. He used to place me in front of him, and when he sent me in he used to put my daughter in front of him — that was Byrne, but Kelly did not do that; and he went round soon after that to look for bushes to set fire to the place. Byrne sent in my daughter after some time and she was kept inside. I went in afterwards, and they (the police) just got me by the clothes and one of the men, Dowling, said, ‘Stop inside, and if they set fire to the place, they (the police) would let both of us out.’ They (the police) said they did not think the outlaws would set fire to the place while women were inside, so I stopped in. Before I came in the last time, Dan Kelly had the bushes outside the room where the men (police) were. He took out a box of matches and struck a match and the wind blew it out; when I saw him strike the match, I said, ‘If you set fire to the house, and the girl get shot or burnt, you can just kill me along with them.’ Dan said nothing at the time, but some time after he sang out to Byrne to send me inside, and I said it was no use my going in — that I would be burned with the rest; and he said he would see about that. So I went in, and we all remained inside till daylight. The first time I went into the room the men (police) appeared as if they were bustling about looking for their firearms, and the second time I went into the room Alexander and another man were sitting on a box in front of the door with their ’possum rugs around them, and I could not see the other men; I did not notice them in the room. I could not say where they were at the time. The third time I went into the bedroom they had my daughter kept in (this was the last time Byrne sent me in). Alexander was at one side of the room and the other constables were under the bed. Constable Alexander was at one side of the room where the bed was not. Constable Duross and Constable Dowling were under the bed, and their head and shoulders out at the side of the bed. I went to the two men, and they caught me by the clothes and pulled me to the ground. I remained lying on the floor; they did not put me underneath the bed. Duross just tried to shove me in slightly, but I remained where I was; in fact, I do not think that I could get under the bed.

“At the time that Byrne was standing at the door no doubt if the police had come to the side of the door they could have fired at him right enough. Of course, I know that we cannot do without police in the country, for any honest person could not live, but they ought to speak the truth. My opinion of some of them is they are not particular what they say. I am quite certain about the two men, Duross and Dowling, being under the bed and their heads out, and the guns facing them by the door, and that was when they pulled me down, and Dowling said if I did not keep quiet they would have to shoot me. He said, ‘You have better stop in, Mrs. Barry, and if you stop in the outlaws will not set fire to the place while there are women in the place.’ That might be about nine o’clock. Of course, it has been said that there were voices outside during the night, but I did not hear any, and I can hear as well as anyone.”

Mrs. Aaron Sherritt, on July 21, 1881, on oath said: “When her husband, Aaron Sherritt, was shot she saw Dan Kelly about a quarter of an hour after the shooting standing inside the front door; he had his elbow leaning on the table. The men (police) could have shot him there if they tried; if the police had been looking out of the door or keeping an eye on the division — the partition that was between the two rooms — they could have had Dan Kelly very easily; but I do not think they were prepared at the time.”

Question (by the Commission): It would not take them all that time to look for their arms? — “Not at that time; there were two of them under the bed. I am quite certain that there were two under the bed and two lying on top; so it was impossible to have either of the outlaws in the position the men (police) were in. They (the police) were in that position when Dan Kelly was in the room. I was put under the bed. Constable Dowling pulled me down, and he could not put me under, and then Armstrong caught hold of me, and the two of them shoved me under, and they had their feet against me. They remained in that position for two or three hours. I do not remember hearing voices outside after I was put under the bed, only the dog howling. I heard no voices outside after my mother came in, and remained — not after that — I did not hear anything. The second time I came in Dan Kelly was by the table, and then when I went out again he was gone to get bushes to set fire to the house.”

ANTON WEEKES.

On July 20, 1881, Anton Weekes on oath said: “I remember going up to Sherritt’s door and asking the way the night Aaron Sherritt was shot. I was stuck up by Byrne and Dan Kelly. They asked me my name. Then they put handcuffs on me and made me go up to Sherritt’s door, and ask him to show me my way. I was there about six o’clock, and I left the place about nine o’clock. I then went home. I live a quarter of a mile from Sherritt’s. After Sherritt was shot I stood an hour or two with the people outside. Byrne was with me, and Dan Kelly was at the front door. I did not hear any conversation with Mrs. Sherritt or Mrs. Barry. They came out and went in again. I had no chance of escaping.

“At about nine o’clock Byrne took the handcuffs off me and left me standing. I stayed there by myself for 15 or 20 minutes, and then I went round home through the bush. I was so frightened I ran directly home and stayed at home. I did not see any others there, only Joe Byrne and Dan Kelly. I heard Byrne call out, ‘Dan, stand and watch the window.’ That is how I knew it was Dan. They were on horseback when they stuck me up, and Byrne was leading another horse. I do not think they had armour on, not Byrne — I think Kelly might; he looked very stout. He had nothing on his head (no armour). I could see his face. I did not see them try to set the house on fire. Byrne always called out for two men to come out, and said, ‘Mind, I will set the house on fire if you do not come out.’ But he never began to do it while I was there. Byrne did not say there were police in the house; always two men he wanted out. I knew Byrne since he was a child. He was a neighbour of mine half a mile away. I heard Byrne and Mrs. Sherritt talking and crying, I heard Byrne ask who was there, and she said, ‘A man in there looking for work’, and he said always, ‘Bring the man out,’ and he sent Mrs. Sherritt in to bring the man out. I did not know that there were police in the house, and never heard it. I did not hear anyone say there were policemen about there till after the murder.”

The four constables in the bedroom had more confidence in the chivalry of the Kellys than in their own courage. These “heroes” put Mrs. Sherritt between them and the wall under the bed. She would stop a bullet if one came through, but they were very confident that the Kellys would not fire a shot through the wall while there were women inside. It is perfectly clear that no attempt had been made to set fire to the house. Next day, Sunday, the four constables remained inside until six o’clock on Sunday evening. If the order were reversed and two outlaws were in the bedroom and four constables outside, what a different state of affairs would have prevailed! The four constables would, undoubtedly, have been captured. Later, at Glenrowan, there were fifty police to Dan Kelly and Steve Hart, and then the police were not confident of success.

Supt. Hare agreed with Joe Byrne that Aaron Sherritt was better dead than alive. He (Supt. Hare) wrote as follows:— “It was doubtless a most fortunate occurrence that Aaron was shot by the outlaws; it was impossible to have reclaimed him, and the Government of the colony would not have assisted him in any way, and he would have gone back to his old course of life, and probably become a bushranger himself.”

Source:

J. J. Kenneally, The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers, Melbourne: J. Roy Stevens, 5th edition, 1946 [first published 1929], pages 192-207

[Editor: Corrected “such compenastion” to “such compensation”; “match, said” to “match, I said”.]

Leave a Reply