Published in 1964, the book is full of light-hearted predictions of how the world will turn out in the future. For example, China and Japan are allies, South Africa has twelve independent black states, the USA has three breakaway independent black nations (mostly Muslim), and the Soviet Union has fourteen splinter nations. Also, Australia has implemented conscription for sports people (making the country the foremost sporting nation in the world). Prophetically, the author mentions President Nixon (p. 61), even though Richard Nixon did not become US President until 1969 (although, Nixon was seen as a serious contender for high office in 1964).

The basic storyline is about how Australian scientists create a virus to combat rabbits, which is then used by an autocratic Prime Minister as a biological weapon to threaten and control the world.

It’s an intriguing and whimsical story; the product of a fertile mind.

Australia is in trouble. On of the country’s largest land owners, Sir Alfred Hill, has about two million rabbits on his property (called Bludgerton). It appears that all of the rabbits are resistant to the scientist-introduced Myxomatosis virus, so the usual bio-warfare against them won’t work. If these two million Myxomatosis-resistant rabbits get out of the currently well-fenced-in property, then the countryside all around is going to be swamped; all of the food being grown on nearby farms will be eaten – and then how far will the two million rabbits spread after that?

The Prime Minister, Kevin Fitzgerald, calls in scientists from the CSIR (called the CSIRO from 1949 onwards — perhaps the author used the old name to avoid a potential lawsuit?), and demands that they fix the problem; otherwise, there are plans afoot to nuke the property with atomic mortars.

Just before the deadline for the nuclear solution, the scientists test their new anti-rabbit chemical concoction, Supermyxomatosis, but, instead of dying, the rabbits turn savage and attack their handlers, killing Sir Alfred. And so, with the failure of the new virus, the property is nuked. Problem solved (apparently).

The Minister of Defence realises that, with the development of Supermyxomatosis, Australia could have in its possession a world-beating biological weapon. The PM orders the CSIR scientists to refine the formula, so as to make it fatal to humans. When that deadly and dastardly conversion has been done, vials of the virus are hidden in key places around the world, ready to be activated by radiowaves. And then the fun begins.

The PM summoned all of the world’s leaders to the Opera House in Sydney, for a meeting on Christmas Day. On being informed that none of the leaders were willing to come, let alone listen to him, the PM directed that the warring black and white armies of Rhodesia, along with the intervening United Nations army, should all stop fighting, or else they would be hit with the Supermyxomatosis virus. Of course, no-one listened, and so the three armies were wiped out as an example of Australia’s might. The PM then demanded that the US, Russia, Britain, and France nuke the affected area, because otherwise the virus would keep on spreading, until it wiped out all of Africa, Asia, and Europe. And, so, nuke the area they did.

Incensed by Australia’s threats, China and Japan decide to invade Australia, and send a naval convoy, crammed full of 500,000 soldiers, and accompanied by a large number of battleships, towards Australia’s top end. However, the sneaky Australian security services have an answer for that — foreign students, back home in Singapore for the Christmas holidays, are blackmailed into planting some of the Supermyxomatosis devices inside of the armada’s supplies of rice. So, soon after the invasion fleet departed, the biological warfare devices were set off, and all of the troops died. No country ever dared to oppose Australia ever again.

With all of the world’s leaders gathered in the Sydney Opera House on Christmas Day, the Australian Prime Minister addressed them, and told them to stop engaging in war, to undergo total disarmament, to spend half of their current military budgets on cutting taxes and the other half on helping the Third World, and to exile all of their nuclear physicists to the Falkland Islands. And, so, Australia imposed world peace on the planet — Pax Australiana.

It was also a condition that the world powers, as part of their disarmament, had to send some of their long-range nuclear missiles to Australia, thus making the Land Down Under the world’s only nuclear power.

However, as time went on, it was found that the leaders of the world were having a hard time settling disputes without warfare. Therefore, the Australian PM came up with a solution. He decided to hire out the Woomera testing range as a battlefield for disputing countries to fight in (charging both sides a hefty fee in the process — with the Australian government making a huge profit). Also, both sides would have to buy all of their armaments from Australia (another profitable arrangement); as well as which, the warring parties would be charged for the food and supplies needed to feed and look after their troops (even more profit for Australia). At the prompting of the Minister for Tourism, the PM announced that combatants would be allocated separate cities for rest and recreation (making even for profit for Australia when the troops spent their money whilst on leave). The Land Down Under would also take care of all POWs, putting them to work (at union rates) on national projects — with the Australian government being compensated for its expenses and outlays from the warring nations (which had to pay with bars of gold). War was turning out to be quite a profitable venture for the Australian super-power.

As a twist in the tale, behind each warring army an office of Desertion and Immigration was established. Any soldier wanting to leave the field of combat could easily desert and sign up as an immigrant to Australia. Wars were even put on a timetable so as to match up with Australia’s labour shortages.

According to the book, Communist Russia was just about the only country left in the world with any decent culture, as the non-communist world had concentrated too much on science and technology. Regarding the Latin classics, the Prime Minister opined that “The Russians know it all”, and he decided to “break that Soviet monopoly on culture”. Apparently, Scotland and Ireland also had some culture, so wars involving those three “cultured” nations were arranged, with Australia to gain from the culturally-gifted deserters — “And culture returned to Australia.” One could guess that this was the author’s way of ridiculing the foolish “Australia has no culture” notion, spread by fools and anti-Australian critics; the other possibility is that the author intended it as a way to reinforce that stupid notion (see pp. 85-88); which slant on the idea was intended is not really clear.

In the meantime, it was discovered that some rabbits had survived the bombing at Sir Alfred’s property. These were no ordinary rabbits, as they had lived through being infected by the Supermyxomatosis virus, and had survived the radiation of atomic bombs — they were mutations as big as a decent-sized dog, and smart to boot. So, Bludgerton was nuked again.

With Prime Minister Fitzgerald leading Australia into a golden age of prosperity, his Field Marshall tells him “You’re a superman” and gives him a Roman salute; the PM declares “I was destined to guide my country” (p. 108). At a later stage the PM says that “A man has to be loyal to his Party all the time … The Party comes first because the State comes first — and the Party knows what’s best for the State” (p. 145). Taken along with some of Fitzgerald’s dictatorial methods, these passages appear to be not-so-subtle hints that Australia has become a fascist state (see also pp. 171-172).

The bombing of Bludgerton was too late. The Supermyxomatosis-affected rabbits moved on, and had built new warrens elsewhere. When it was reported that 30,000 sheep were reported killed in one night at a property 180 miles from Bludgerton, the PM knew that it was time to be worried. It was estimated that it took 750,000 rabbits to kill the 30,000 sheep; obviously, the rabbits had mutated from the effects of Supermyxomatosis and nuclear radiation, and had become a clear and present danger.

Eventually the rabbits, under cover of darkness, reached the east coast of Australia; there they built warrens on and near the beaches. However, a hot summer, with a lack of rain, forced the rabbits to go looking for water in populated areas — to find water in swimming pools, fountains, ponds, etc. At dusk on Christmas Day, millions of thirst-crazed dog-sized rabbits invaded the cities of the eastern seaboard, killing hundreds of people, and causing a panic.

As the older generation were the only ones who had dealt with rabbit plagues, it was decided to call up all men aged 60 to 65 to fight this new rabbit menace (this idea, the PM privately stated, would save a huge amount of money, as old age pensions aren’t paid to dead people).

The PM declared martial law, and lots of 60-65 year olds were conscripted for the fight. On the 29th of December the grey force was sent off to set up ambushes at the rabbits’ likely watering holes. In some spots the oldies won, in other places they didn’t. Tens of thousands of rabbits were slaughtered, but many old men were killed as well.

One of the resulting problems of the battles against the rabbits was the need to burn all of the rabbit carcasses, to prevent an epidemic of the Supermyxomatosis disease amongst humans. Crematoriums, garbage dumps, and industrial furnaces were used, but only two-thirds of the dead rabbits were burnt before dusk of the following night (when the rabbits were due to appear again).

Reluctantly, the PM decided to evacuate a large part of eastern New South Wales (east of the Great Dividing Range, and north of Woollongong). On the 30th of December the Australian Army, aided by volunteers, collected the rest of the rabbit dead and burnt them. New Year’s Eve was the date for the great migration, as millions of New South Welshmen (New South Welshpeople?) evacuated to the south.

The 1st of January 2000 was the start of the year of the angry rabbit.

Hordes of rabbits took over eastern NSW, eating cattle, sheep, and all other available animals; then, with all of those resources exhausted, they began to spread north into Queensland and south into Victoria.

Foreign countries offered to take in Australia’s leading sportsmen; PM Fitzgerald drove a hard bargain, whereby 500 Australian refugees had to be taken with each sportsman recruited.

Popular civic movements around the globe demanded that all of the Australian refugees be taken in, and raised funds to aid the humanitarian effort.

The Japanese evacuated people from the Northern Territory; the Americans arranged for the world’s airlines and air forces to evacuate Aussies from all of Australia’s major airports; and the fleets of the world evacuated refugees from all of Australia’s non-eastern harbours.

Like a captain on a sinking ship, Prime Minister Fitzgerald stayed in Canberra until the end, heroically (and practically) refusing evacuation, as he was (by then) in an infected area.

Eventually the rabbits came for Fitzgerald, and he died in his study, having just made the arrangements for the evacuation of the last of his people.

The great evacuation of the Australian people finished in 2003. Les Dorfmann, the last surviving Cabinet Minister, just before he boarded his plane to leave the country, ordered Canberra to be nuked.

The golden age of Australia was over. The rabbits won.

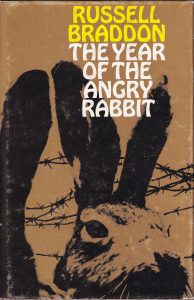

Title: The Year of the Angry Rabbit.

Author: Russell Braddon.

Publisher: William Heinemann: London, 1964.

At the time of this review, The Year of the Angry Rabbit was no longer in print, but a small number of copies were available via some online second-hand book sellers. If the book is ever republished, or if you can get hold of a copy from your local library, then it is worthwhile reading as a piece of light-hearted drama.

Further information:

“The Year of the Angry Rabbit”, Wikipedia

“Russell Braddon”, Wikipedia

Anne Matheson, “Braddon calls his new book “a giggle””, The Australian Women’s Weekly (Sydney, NSW), 7 October 1964, p. 7

Editor’s notes:

Aussie = an Australian; something that is Australian in origin or style; of or relating to Australia or the Australian people

Bludgerton = the name of a fictional property (in The Year of the Angry Rabbit), apparently based upon the word “bludger” (someone who bludges, i.e. someone who does not work very hard, or does not work at all)

CSIR = the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, a scientific research organisation funded by the federal government in Australia; the CSIR was renamed as the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in 1949

CSIRO = the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, a scientific research organisation funded by the federal government in Australia

Myxomatosis = a disease caused by the Myxoma virus, which affects rabbits (especially European rabbits)

nuke = (as a verb) to attack with a nuclear weapon (or weapons); to drop a nuclear bomb (also known as an atomic bomb) on something

Pax Australiana = world peace established by Australia (in The Year of the Angry Rabbit); this term follows that of “Pax Romana”, which refers to the state of comparative peace and prosperity established by the Roman Empire in ancient times (Pax Romana lasted from approximately 27 BC to 180 AD, i.e. just over 200 years)

PM = Prime Minister

POW = Prisoner of War

Rhodesia = a country in southern Africa, now called Zimbabwe

US = United States of America

USA = United States of America

I remember the book. It was so “over the top” that I didn’t keep it. I would love to read it again. Where can I find it? Patricia Cosgrove

The Year of the Angry Rabbit has become relatively rare.

Vialibri lists 9 copies available for sale, ranging from US$64 to US$309 (the 1967 editions are cheaper than the 1964 editions).

https://www.vialibri.net/searches?title=%22Year+of+the+Angry+Rabbit%22&sort=price.asc

You could also try your local library; if they don’t have a copy, you could ask them to get one in via Inter-Library Loan.