[Editor: This is a chapter from The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers (5th edition, 1946) by J. J. Kenneally.]

CHAPTER XVIII.

EVIDENCE.

Constable Bracken had seen where the Kellys had put the key of the room in which he and others had been imprisoned, and watching for his opportunity, while the Kellys were getting into their armour, opened the door and escaped from the hotel. The other prisoners feared being shot if they followed Bracken, and so decided to remain in the hotel. He rushed over to the railway station, into which the train had just come. Supt. Hare had already given orders to unload the horses, but on hearing from Constable Bracken that the Kellys were in Jones’ hotel, and that the place was full of people bailed up there by the Kellys, he then called his men to let their horses go and follow him. Supt. Hare led the way, followed by Constables Kelly, Barry, Gascoigne, Phillips, Arthur, Inspector O’Connor, and five Queensland blacktrackers.

The Kellys did not fire a single shot until Ned was wounded, which was the third volley from the police. Ned went to the hotel and called out to those inside, “Put the lights out and lie down.” He then went around the back of the hotel and met Joe Byrne, who informed Ned that Constable Bracken had escaped. Ned told Dan and Steve to go into the hotel and to pull up the counters and barricade the sides of the building. The police now kept up the continuous fire at the hotel. The bullets went through the weatherboard walls as if they were cardboard. Ned then retired to a spot some distance from the hotel in the direction of the Warby Ranges, and lay down. He was bleeding freely. There was still one cartridge in his rifle.

Supt. Hare retired after being shot in the wrist. He called out to O’Connor to surround the house, and he told Senior-Constable Kelly to do likewise. Hare continued: “Come on, O’Connor, the beggars have shot me; bring your boys with you and surround the house.” Supt. Hare then retired from the field. He went over to the railway station and ordered the train back to Benalla so that he could receive medical attention. He did not offer to take the women, Mrs. O’Connor and her sister, Miss Smith, back to Benalla with him; they were left to take their chance of being shot. Hare appeared to be bent on self-preservation. His wound was dressed by Dr. Nicholson, but he (Supt. Hare) also sent for his cousin, Dr. Chas. Ryan, of Melbourne. Hare did not return to the fight. The screaming of the women and children in the hotel was heartrending, but the police, as if craving for someone’s blood, kept up a continuous and murderous fire on them. It was a bright moonlight night. Mrs. Jones’ boy was shot by the police early in the encounter. Some of the civilians got out during a short lull in the murderous fire on the women and children from the ranks of the police. Mr. James Reardon and his wife and children tried to escape from the hotel about daybreak, but were driven back by the volleys of hissing bullets directed towards them. They went into the hotel again. Mrs. Reardon saw Byrne, Dan Kelly, and Steve Hart in the passage. She said to them, “Will you allow us to go?” One of the three replied, “Yes, you can all go, but if you go out the police will shoot you.” Mrs. Reardon put her little girl out in the yard and she screamed, and she herself followed and screamed. Dan Kelly said, “If you escape ——” “What will I do?” said Mrs. Reardon. He replied, “See Hare and tell him to keep his men from shooting till daylight, and to allow these people all to go out, and then we shall fight for ourselves.”

“I could see the men behind the trees. A voice said, ‘Put up your hands and come this way, or I will shoot you like —— dogs.’ The voice came from a tree behind the stable on the Wangaratta side. I did not know at the time whose voice it was. It was Sergeant Steele, but at the time I did not know who it was; I saw him afterwards. I put my baby under my arm and held up my hand, and my son let go one hand and held the other child by it, and we went straight on. The man commenced firing, and he kept firing against us. I cannot say he was firing at us, but against us. He was firing in my direction, and I got close to the fence, and the tree stood some distance from the fence of Jones’ yard, and as I did I saw a gun pointed at me. I then turned round and went down along the fence towards the railway station, and two shots went directly after me, and two went through the shawl that was covering the baby. I felt my arm shaking, and I said, ‘Oh, you have shot my child!’ I have the shawl here with two bullet holes in it. (Shawl produced and the holes in it examined). I do not know whether it was two shots or one, and the holes have got a good deal larger since. The shawl was doubled and wrapped round the baby. There were two holes in the shawl when I first looked at it. It came from a gun, for I was very close to it. My son was close behind me, coming about a yard away from me, and he said, ‘Mother, come back; you will be shot’; and I said, ‘I will not go back; I might as well be shot outside as inside’; but I said, ‘I do not think the coward can shoot me.’ My son turned away and walked back towards the house, pulling the little child by the left hand, and with the right hand up. I looked round and saw him going, and that was the last I saw of him. It was quite bright; I cannot say whether it was daylight or moonlight. It was sufficiently light to tell a man. I heard the police call to Sergeant Steele, saying, ‘Do not shoot her; you can see it is a woman with a child in her arms.’ It came from a policeman close behind Sergeant Steele. I found out afterwards that it was a constable named Arthur. My son was two yards from me. My son was two yards from me. Just as I turned two shots went past me. I did not see my son shot. He got shot when retreating to the hotel. He said it was just as he was going to the door, and he fell against the door. No one called out to me to stop or they would fire before the shots came. Only one called out what I have said, ‘Put up your hands or I will shoot you like —— dogs’; and we went where the man called us. I could not be mistaken for a male. I was dressed in my ordinary female attire, and not only that, but they had been firing from the station at me. There was a gutter along there, and when Steele commenced shooting at me they all began shooting at me from the other place. I cannot say the exact words Constable Arthur used. I heard him say at the first set-out, ‘Do you not see it is a woman with a child in her arms?’ — and when those two shots were fired at me I heard him (Constable Arthur) speaking very angrily, and then the firing ceased. I know that Ned Kelly was captured after what I am now relating. I walked straight on to the slip-panel, and I got behind a tree, and, when all the firing had ceased, I called out for them (the police) to spare my life — that I was but a woman, and for a long time nobody spoke. And then Guard Dowsett came out from the railway station, and, as I was not able to get there alone, he helped me to the station. I do not know how he got me there, whether it was over the fence or through. I did not see my son (wounded) until about ten o’clock in the day. He remained at the hotel after being shot, until the male prisoners were released. That was the first time I knew he had been shot in the morning. I was very much excited when I attempted to leave the hotel a second time, when I got into the yard and found how I was treated by the police. I thought my life was in danger. I knew it was in danger. I knew it was a constable who shot at me from behind a tree, for there were no others there. I found out who it was that shot at me by inquiring. I know I am speaking very strongly against that man (Steele). I found out particularly that same afternoon Sergeant Steele told my second eldest boy, some sixteen years of age, that it was he (Steele) who shot him (my eldest son). Another lad from Winton — I think a son of Mr. Aherne — was speaking to my second boy about the shooting affair. The latter said, ‘My brother was shot,’ and the other lad asked by whom, and Sergeant Steele made answer and said, ‘It was I who shot him’ — so I think that is plain enough. I stated that Constable Arthur remonstrated with him (Steele) for shooting. I did not know him (Arthur) at the time, but two months afterwards I saw him and recognised him, and inquired as to his name, and found it was Constable Arthur.”

CONSTABLE JAMES ARTHUR.

On June 9, 1881, Constable James Arthur, giving evidence on oath before the Royal Commission, said:— “I remember Mrs. Reardon coming out, and her son and Mr. Reardon. It was near daylight. I was thirty yards from the house on the Wangaratta side of Jones’ Hotel. I was stationed between the back and front, opposite in a line with the passage, about due north from the house. I heard Mrs. Reardon cry out. When she came out she screamed. I could not make out what she said. She screamed out as loud as she could and had a child in her arms, and when she came out Steele sang out, ‘Throw up your hands or I will shoot you like a —— dog,’ and the woman was coming towards him and he fired. He fired direct at her; we could see it in the moonlight, and then she turned round, and then he fired a second shot, and then I spoke to him and told him not to fire — this was an innocent woman. I could see her with a child in her arms; and then afterwards he turned round and said, ‘I have shot the mother Jones in the ——.’ Constable Phillips was on his right, on the right hand behind, and I heard him make some remark about a feather. I could not say what it was. I told him (Steele) not to fire — it was an innocent woman. I said I would shoot him if he fired. I was about twenty yards from him (Steele). They came out of the back door of the hotel, out of the passage, and just as she came out of the passage Steele fired. Right behind the hotel I saw her (Mrs. Reardon’s) son coming out. I saw the young fellow coming out, leading a child. I could distinguish it was a figure of a man. I could see it was a young man. It was quite light. He was walking, leading the child. I could not be positive that Steele deliberately fired at that young fellow, because he (young Reardon) was nearest to me and Steele had to fire past me. I have no hesitation in saying Steele deliberately shot at the young fellow. He shot at him. I did not see him fall with the shot Steele fired, but with another shot he fell in the doorway. I would not swear it was Steele who fired the second shot. Steele made no remark then. After the youth a man came out with a child in his arms, and Sergeant Steele sang out to him to hold up his hands. The man threw up his arm, and he (Steele) fired at him. The man (Reardon) crept on his stomach, and crept into the house. He (Steele) seemed like as if he was excited. He fired from the tree when he first was there. He fired when I could see nothing to fire at. I did not see that he had been drinking. When he came first in the morning he came to where Constable Kelly and I were standing, and we went to tell him about the outlaws being in the house, and he would not wait; he rushed over to a tree close to the house, leaving his men to place themselves. He did not place his own men or anything — he would not wait.”

Question (by Commission): Who placed his men? — The senior constable took two, and the others went by themselves.

Question: You recollect you are on oath; are you quite positive in those statements you have made? — I am.

Question: And that young Reardon was not crawling? — He was not, not when he came out.

Question: And the man that held up his hands after, you say Steele fired at him? — Yes.

Question: We have it in evidence that the elder Reardon fell on his knees and belly and crawled in? — That is what I say. I would not swear it was Reardon, or young Reardon, but those that came out after Mrs. Reardon.

Question: You have no doubt in your mind that this was a woman? — Any man could see her and hear her voice.

Question: You had no suspicion in your mind that it was one of the outlaws? — None at all.

Question: You could tell the voice? — Yes.

Question: Sergeant Steele had the same opportunity of knowing that as you? — Just the same.

Question: Did he make any remark when you said you would shoot him if he fired again? — No; the only one was that he had shot Mrs. Jones in the ——.

CONSTABLE WILLIAM PHILLIPS.

On oath on June 9, 1881, said:— “I saw Mrs. Reardon come out of the house.”

Question: The first thing I heard was Steele challenging somebody and firing, and then I heard a woman screaming; and with that, from the front of the house several shots came up. I heard Constable Arthur say, “Do not shoot — that is an innocent woman,” or “That is a woman and children” — something to that effect.

Question: Was there any difficulty in yourself, Arthur, or Steele knowing that is was a female? — Not the slightest.

Question: Before he fired you could see distinctly it was a woman and children? — Yes, it was bright moonlight.

Question: Did Steele shoot immediately he challenged them? — Immediately.

Question: Did you hear him (Steele) say anything? — First, I asked him what he was shooting at, and he said, “By Christ, I have shot old mother Jones in the ——”; and I said, “It is a feather in your cap.”

Question: Did you see what happened after? What did the woman do? — She was singing out and went out of the place. Steele was at some (one) of the trees there, and she walked down. The fence was between her and Steele, and that was what saved her, no doubt. After he fired there was loud talking going on and screaming, and I do not know who took her away.

Question: She was taken away, at all events? — Yes, and did not go back to the house.

Question: Did you see any other figure besides her? — No, only the boy.

Question: Where was he? — He was following her, and all at once I saw him run back to the house.

Question: Did you not see that he had hold of a child? — No, I could not swear that.

Question: Did you hear anyone challenging the boy? — Sergeant Steele was the only one who challenged them.

Question: Did you see whether the boy was crawling? — Walking.

JAMES REARDON, RAILWAY LINE REPAIRER.

On May 14, 1881, on his oath, stated to the Royal Commission:— “Shortly after two o’clock on Sunday morning, June 27, 1880, I heard the dogs barking, making a row, and I got up and dressed myself and went outside the door and heard a horse whinnying down the railway line, and went towards where I heard the horse. I thought it was the horse of a friend, and I went down, and Sullivan was coming through the railway fence, and I said, ‘What is the matter?’ and he said, ‘I am taken prisoner by this man.’ Ned Kelly came up and put a revolver to my cheek and said, ‘What is your name?’ and I said, ‘Reardon,’ and he said, ‘I want you to come up and break the line.’ He said, ‘I was in Beechworth last night, and I had a great contract with the police; I have shot a lot of them, and I expect a train from Benalla with a lot of police and blackfellows, and I am going to kill all the ——.’ I said, ‘For God’s sake do not take me; I have a large family to look after.’ He said, ‘I have got several others up, but they are no use to me,’ and I said, ‘They can do it without me,’ and he said, ‘You must do it or I will shoot you’ — and he took my wife and seven or eight children to the station.

“When we came to the small toolhouse the chest was broken and the tools lying out on the side of the line. He said, ‘Pick up what tools you want,’ and I took two spanners and a hammer, and I said, ‘I have no more to take,’ and he said, ‘Where are your bars?’ and I said, ‘Two or three miles away’; I said, ‘In front of my place,’ and he sent Steve Hart for them, who came in a few minutes after himself. When I went on the ground I said to Hart, ‘You have plenty of men without me doing it.’ ‘All right,’ he says, and he pointed to the contractor from Benalla, and said, ‘You take the spanner.’

“That was Jack McHugh, I think. He took the spanner and I instructed him, on being made, how to use it. Ned Kelly came up and said, ‘Old man, you are a long time breaking up this road.’ I said, ‘I cannot do it quicker.’ And he said, ‘I will make you do it quicker; if you do not look sharp, I will tickle you up with this revolver.’ And I said, ‘I cannot do it quicker, do what you will’; and he said, ‘Give me no cheek.’ So we broke the road. He wanted four lengths broken. I said, ‘One will do as well as twenty.’ And he said, ‘Do you think so?’ And I said I was certain. I said that, because I thought if only one was off, the train would jump it and go on safely. Hart pointed out the place.

“He then brought us all up to the station and remained at the gatehouse, where the stationmaster lived, for perhaps two hours. There were about twenty of us. All who came along were bailed up, and on Sunday evening he (Ned Kelly) had 62 which I counted.

“At the hotel he did not treat us badly — not at all. They had drink in them in the morning. When I first saw Steve Hart he was pretty drunk. I saw some people offer drink to Dan Kelly and Byrne, I believe, and they said, ‘No’; but if Ned Kelly drank I cannot say, for he was in the kitchen in the back. When it came night we were all locked in and kept there. There was no opportunity of escaping at all — not the slightest. No chance. I was there when the police came. I was still there when he went for Bracken between nine and ten o’clock on Sunday night. They took him prisoner also. There was only one constable here at the time. During the night before the police came they were very jolly, and the people and Mrs. Jones cleared the house out. They would not have it without a dance. She wanted me to dance, and I said, ‘No, something is troubling me besides dancing.’ Mrs. Jones said, ‘We will all be let go very soon, but you may thank me for it’; and my missus asked Dan Kelly to let me go home with my children and family. ‘We will let you all go directly,’ she (Mrs. Jones) said. That would be two o’clock, about an hour before the police arrived.

“There was a dance got up in the house; there were three of the Kellys, Ned, Dan and Byrne danced, and Mrs. Jones and her daughter, and three or four others I did not know. Mrs. Jones praised Ned Kelly; she said he was a fine fellow. Dan Kelly said, ‘Now you can all go home,’ and I stood up and picked up one of my children in my arms, and we were making for the door when Cherry picked up Ryan’s child, and Mrs. Jones stood at the door and said, ‘You are not to go yet; Kelly is to give you a lecture,’ so we all turned back into the house again, and Mrs. Jones came in and said, ‘Kelly will give you all a lecture before you go.’ A little later Byrne came in and said, ‘The train is coming.’ That stopped all the discourse. They turned into the back room — the three bushrangers; there was one (Steve Hart) taking care of Stanistreet’s family. Then they went into one of the back rooms, dressing themselves in their armour. I could hear the armour rattling. We could have got clear away if we had been allowed to go when Dan Kelly said we could go.

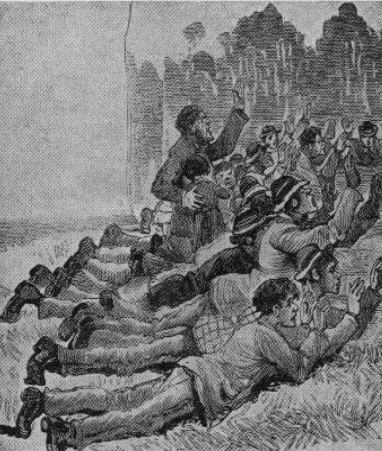

“Mrs. Jones seemed to be very pleased that the outlaws were there. Bracken saw where they planted the key, and at the time they went to put their armour on he went and took the key. He put the key in his trousers pocket and came back to the door and stood there till he got his opportunity, and opened the door and turned the key in the lock. When the police came the outlaws went round the house and fired. There were three (Dan, Byrne and Steve Hart) who came in again. I do not believe Ned came in at all. The police fired at once. There was a return shot immediately. There were two or three hot volleys very quick. We could see the light (outside). There was no light in the house. We were all frightened, and Bracken told us to lie down on the floor as flat as we could before he went away. The Kellys said they would allow us all to go if the police would. There was a tall chap — I forgot his name — he put a white handkerchief out of the window, and there were three bullets sent in at once. The shots went straight from the drain into the window. He threw himself on the floor. After the second or third round was fired things got quiet for a bit, when Hare said cease firing. Ryan and his wife and three or four children and three of mine, and a strange woman from Benalla, then rushed out, and the firing was on them as hard as it could be blazed from the drain, and I could not say where, and I rushed out and my son with me. It was just daylight. My wife and I got out, and we had to go back into the house because of the firing. The firing was from all directions. The most part of it was from the drain. The fire was strong up from the drain, and Mr. O’Connor popped his head up from that drain and said, ‘Who comes there?’ with a loud voice. I recognised the voice. Ryan sang out, ‘Women and children,’ and the firing still continued.

“We went back again and said to Dan Kelly, ‘I wish to heaven we were out of this.’ Byrne said, ‘Mrs. Reardon, put out the children and make them scream, and scream yourself, and she was coming past the rifles in the passage, and one of the rifles tangled in her dress, and Dan Kelly said to Byrne, ‘Take your rifle, or the woman will be shot’; and I came out and she screamed, and the children, and they came out. The fire was blazing and a policeman called out — I thought it was Sergeant Steele — ‘Come this way’; and he still kept firing at her — at my wife with the baby in her arms. (He was not covering her.) Firing at her and covering her are two different things. She has a shawl with a bullet hole through the corner of it which she can show you. I heard a voice saying, ‘Come this way.’ Constable Arthur was standing close to Sergeant Steele, and he said, ‘If you fire on that woman again, I am —— if I don’t shoot you, cannot you see she is an innocent woman?’ These were Arthur’s own words, and I did not believe that the man would do that. Then I had to return back; there were bullets flying at me, and I crept on the ground, and went back to the house with the children, and as my son returned he got wounded in the shoulder, and fell on the jamb of the door, and he has got the bullet yet, and he is quite useless to me or himself. I would sooner have seen him killed. He is getting on to nineteen. I returned back to the house then and lay down among the lot inside, and put the children between my knees, when a bullet scraped the breast of my coat and went across two other men, and went through the sofa at the other end of it. We remained there expecting every minute to be shot, until we heard a voice calling us to come out, about half-past nine in the morning (Monday). We got ten minutes. I think it would be Mr. Sadleir’s voice, to the best of my belief. I cannot say for certain. Mr. Sadleir was the first I recognised after I came out. We all came out. I was the last, for I had the two children, one in each hand, and as I was coming down there was a constable named Divery, and he said, ‘Let us finish this —— lot,’ or something like that. Then the terror of that drove me — I ran to the drain. A blackfellow there cocked his rifle at my face, and I did not know what to do with the children, and I ran away up to where Mr. Sadleir was.”

By the Commission: That was hot work. — Hot work! You would not like to be there, I can tell you.

“Byrne had been shot at the end of the counter, going from the passage. He was standing still. I only heard him fall. I heard him fall like a log, and he never groaned or anything, and I could hear a sound like blood gushing. That was about five or six in the morning; but when I was coming out, the other two (Dan Kelly and Hart) were both standing close together in the passage, with the butt end of their rifles on the ground (floor). They were struck while I was there; I could hear the bullets flying off the armour several times. Their lives were saved for the time being by the armour. They fired many shots before that in the early part, but I believe from the time it became daylight they did not fire but very few times that I could notice.”

Question by Commission: At the time that Steele, you say, was firing upon you, and your wife escaping, were the outlaws firing from the hotel? — No, I am positive they were not.

Question: Why? — Because they were standing still, and I could hear if they did. They (Dan Kelly and Hart) said they would not fire until we escaped. Sergeant Steele told me and several others that he had shot my son.

Supt. Hare went to Benalla shortly after he received a wound in the wrist. In his absence Senior-Constable Kelly was in charge.

Sergeant Steele seemed to be too intent on shooting at women and children to take command. At about six o’clock Supt. Sadleir arrived from Benalla with reinforcements, and he was from that hour in supreme command. There was no order or discipline among the fifty policemen and several civilians who were assisting the police. At about seven o’clock a figure like a blackfellow appeared up in the bush. Someone called out, “Look at this fellow.” Senior-Constable Kelly called out to Guard Dowsett to “Challenge him, and if he does not answer you, shoot him.” Ned Kelly, who in armour and helmet looked like a blackfellow, pulled out a revolver and fired at Constable Arthur. Three or four constables fired at him, and he advanced. On coming towards the house in the direction of Jones’ there were several shots fired at him; they had no effect. Constable Kelly sang out, “Look out! he is bullet proof.” Ned Kelly was coming towards the position which Sergeant Steele had taken up. Dowsett fired at him with a revolver. Ned Kelly was behind a tree, but one hand was projecting outside the tree. Constable Kelly fired at the hand and missed; he fired again and hit the hand. Ned still advanced and moved over to a fallen log at Jones’ side of the log. Ned was coming from the Wangaratta side of the hotel, and was coming from the direction of the Warby Ranges. Several policemen fired at him. Senior constable Kelly said, “Come on, lads, we will rush him.” Ned was firing under great difficulties. He appeared to be crippled; he was holding up his right hand with his left hand; consequently his shots fell short and struck the ground half-way. Steele now came close up behind Ned and fired at him. Constable Kelly fired two shots, and Steele also fired, and Ned Kelly dropped on his haunches. Steele ran and caught him by the wrist and under the beard. The helmet was on. Steele had one hand on his neck. Constable Kelly pulled the helmet off and said, “My God, it is Ned!” Constable Kelly threw Ned over on Steele.

Constable Dwyer rushed up and kicked the captured bushranger while he was held down. Steele was about to shoot him with his revolver, when Constable Bracken prevented him. Steele seemed thirsting for blood — someone’s blood. One of the police thought Ned Kelly was a ghost; some thought it was the devil. They were all in a state of great excitement, and Ned Kelly was taken to the railway station and examined by Dr. John Nicholson. It was now known that Joe Byrne was dead. There were only Dan Kelly and Steve Hart left. As the day wore on the fifty policemen continued to fire at the hotel.

Dr. John Nicholson, of Benalla, made history by suggesting to Supt. Sadleir that the latter should wire to Melbourne for a field gun (cannon) in order to make sure that these youthful warriors should not outwit the police and escape.

Supt. Sadleir sent a wire to headquarters in Melbourne for a cannon to be sent up to blow up the hotel. It was also known to the police that Martin Cherry was lying dangerously wounded in the detached back room of the hotel.

Wire sent to Supt. Sadleir to police headquarters, Melbourne:—

“Glenrowan, June 28, 1880.

Weatherboard, brick chimney, slab kitchen. The difficulty we feel is that our shots have no effect on the corner, and there are so many windows that we should be under fire all the day. We must get the gun (cannon) before night or rush the place.”

The cannon had reached Seymour when the hotel was burnt down, and, on this information being received, it was returned to Melbourne.

The odds of 25 police to one youth was not considered sufficient. The valour of 50 policemen to two youths, one nineteen years of age and the other twenty years old, would be equalised if the 50 policemen also had a cannon with which they could stand off and blow the two bushrangers and Martin Cherry, a wounded civilian, to pieces. The police now had Ned Kelly’s armour and helmet, and could have used it on a constable to enter the house. But the police seemed to be short of one important part of the necessary equipment — courage.

Affidavit of John Nicholson, Doctor of Medicine, and legally qualified to practise in Victoria.

I, John Nicholson, Doctor of Medicine, and legally qualified to practise in Victoria, make oath and say as follows:—

I reside in Benalla. I was called early on Monday morning, 28th June, 1880, by Superintendent Hare, who said that he had been shot by the Kellys, and wanted me to go on to Glenrowan, where the police had them surrounded in a house. I wanted him to wait a minute or two until I put on some clothing and I would dress his wound. He would not wait, but said he would go on, and I was to follow him over the bridge. Mr. Lewis, Inspector of Schools, was with him. I shortly afterwards went to the post office, which is about three-quarters of a mile from my residence. I met Mr. Sadleir, who told me Mr. Hare was at the post office, and he said he would wait a quarter of an hour for me, and I was to go with him to Glenrowan.

I then went and saw Mr. Hare, who was lying on some mail bags in the post office. I ascertained that he had been wounded in the left wrist by a bullet, which had passed obliquely in and out at the upper side of the joint, shattering the extremities of the bone, more especially of the radius. There were no injuries to the arteries, but a good deal of venous haemorrhage in consequence of a ligature which had been imprudently tied around the wrist above the wound. I temporarily dressed the wound, during which he fainted. He did not complain of being faint when I first saw him at my residence. Seeing that the wound, although serious, was not dangerous to life, I made all haste to the railway station and accompanied Mr. Sadleir and party to Glenrowan. Mr. Sadleir asked me what I thought of Mr. Hare’s wound, and I told him that it would be a question whether amputation of hand would not be the best course to adopt, as the wound was of such a nature that recovery would be very protracted, and might endanger life.

We arrived at Glenrowan before daylight, but the moon was shining. The men, under Mr. Sadleir’s instructions, then immediately spread, having first ascertained from Senior-Constable Kelly where the guard was weakest. A party headed by Mr. Sadleir went up the line in front of the house, and were immediately fired at. Three shots were fired in one volley at first, and immediately afterwards a volley of four. The fire was sharply replied to by Mr. Sadleir’s party, and also from other quarters where the police were stationed. I did not see anyone come outside, and thought the return fire was at random. The firing on the part of the police was renewed at intervals and replied to from the house, but never more than a volley or two after this. Mr. Marsden, of Wangaratta, Mr. Hawlins, several gentlemen, reporters for the press, some railway officials and myself were on the platform watching the proceedings, sometimes exposed to the fire from the house, in our eagerness to get a clear view of everything. Things remained in this state for about an hour, when a woman with a child in her arms (Mrs. Reardon) left the house and came towards the station, crying and bewailing all the time. She was met by some of the police and taken to one of the railway carriages.

From her we learnt that the outlaws were still there, and at the back part of the house, but she was too much excited to give any definite information. About 8 o’clock we became aware that the police on the Wangaratta side of the house were altering the direction of their fire, and we saw a very tall form in a yellowish-white long overcoat, somewhat like a tall native in a blanket.

He was further from the house than any of the police, and was stalking towards it, with a revolver with his outstretched arm, which he fired two or three times, and then disappeared from our view amongst some fallen timber. Sergeant Steele was at this time between him and the house, about forty yards away, Senior-Constable Kelly and Guard Dowsett nearer to him on his left, and Constables Dwyer, Arthur and Phillips near the railway fence in his rear. There was also someone at the upper side, but I do not know who it was.

Shortly after this a horse with saddle and bridle (Ned Kelly’s bay mare) came towards the place where the man (whom we had by this time ascertained to be Ned Kelly) was lying, and we fully expected him to make a rush for it, but he allowed it to pass, and went towards the house. Messrs. Dowsett and Kelly kept all this time stealthily creeping towards him from one point of cover to another, firing at him whenever they got a chance. The constables in his rear were also firing and gradually closing in upon him. At last he laid down, and we saw Sergeant Steele, quickly followed by Kelly and Dowsett, rush in upon him, and a general rush was made towards them by the spectators and the other police who had been engaged in surrounding him. When I reached the place, probably two minutes after he fell, he was in a sitting posture on the ground, his helmet lying near him. His face and hands were smeared with blood. He was shivering with cold and ghastly white, and smelt strongly of brandy.

He complained of pain in his left arm whenever he was jolted in the effort to remove his armour. Messrs Steele and Kelly tried to unscrew the fastenings of his armour, but could not undo it on one side. I then took hold of the two plates, forced them a little apart, and drew them off his body. While doing this we were fired at from the house, and a splinter struck me in the calf of the leg. He was then carried to the station, and I examined and dressed his wounds. Mr. Sadleir came after Kelly was brought to the station and asked him if he could get the other outlaws to give in, but he said it was no use trying, as they were now quite desperate. After dressing the wounds I saw Mr. Sadleir, and he asked me whether I thought he was justified in making a rush upon the house. I said to do so against men in armour, such as we saw, was certain to result in several men being severely, if not mortally, wounded, and as the day was young it would be best to wait some time before attempting anything, as there was no possibility of their escape. I then said: “It is a pity we have not got a small gun with us; it would made them give in pretty quick, as their armour would be no protection to them, and the chimney would be knocked about their ears.” Mr. Sadleir said that Captain Standish was starting from Melbourne and would be up a little after mid-day, and he would immediately telegraph to him and mention the matter; but as no time could be lost he would send a telegram at once. The telegram was sent about five minutes after the gun was first mentioned. Possibly if there had been time for mature consideration it would not have been sent at all.

Mr. Sadleir was particularly cool and collected all the time I saw him, but events were not under his control. The crowd which had collected made anything like order utterly impracticable. The position was one of great difficulty, and I do not think anyone would have managed much better. The place might have been rushed, but to unnecessarily risk men’s lives would have been foolhardy, however brilliant it would have looked.

I attribute most of the want of concerted action on the part of the police to Mr. Hare leaving the ground before Mr. Sadleir had arrived and relieved him. There was evidently no necessity for his doing so, because he would not wait at my residence to have his wound dressed, which he would undoubtedly have done had it been at the time greatly inconveniencing him.

I have known Mr. Sadleir for several years, and have invariably found him a painstaking, trustworthy and capable officer. I may add that a great deal of my knowledge of his character has been obtained in my capacity as Justice of the Peace. And I make this declaration conscientiously believing same to be true, and by virtue of the provisions of an Act of Parliament of Victoria rendering persons making a false declaration punishable for wilful and corrupt perjury.

JNO. NICHOLSON.

Declared before me at Benalla on the 16th day of September, One thousand eight hundred and eighty-one. — Robt. McBean, J.P.

THE GREEN SILK SASH.

While the Kellys were living at Wallan, Ned Kelly saved the life of a boy who had fallen into a flooded creek. The boy’s father was so grateful for Ned’s heroic rescue of his son that he decided to make Ned a present of a very valuable “Green Silk Sash with a heavy bullion fringe.”

At the siege of Glenrowan, Ned Kelly received five bullet wounds, and while bravely attempting to rejoin his comrades he fell, overpowered by numbers. He was captured and removed to the stationmaster’s office. While Dr. John Nicholson, of Benalla, was removing Ned’s clothing, he saw the beautiful Sash, and, removing it, rolled it up and put it into his pocket.

Having fainted, Ned was quite unconscious while the doctor secured the sash. After the siege was over the doctor said nothing about the sash, and neither the police nor the public were aware of its existence. But in the year 1901 the doctor’s son, Richard McVean Nicholson, took the sash with him to England.

In 1910 the young Mr. Nicholson was drowned in the Firth of Forth, and the sash was handed over to his sister, Mrs. R. Graham Pole, to whom application has been made for its return to Mr. Jim Kelly, Ned Kelly’s sole surviving brother.

Mrs. R. Graham Pole is the second daughter of Dr. John Nicholson who attended college at Benalla with the Author. Mrs. Graham Pole sent the sash back to Australia with a cousin who was returning to Melbourne. All trace of the sash has been lost.

Still more important than the green sash referred to, is the confiscation by the police officials of the four suits of armour used by the members of the Kelly Gang. The armour of Dan Kelly, Steve Hart, and Joe Byrne is still in official custody, and is in Melbourne. Ned’s armour, with a bogus helmet, is said to have been simply given away to a titled millionaire. The original helmet is still in Melbourne. As Ned had ceased to be an “outlaw,” before he was arrested, and afterwards tried, convicted and hanged by process of law, there was no legal justification for confiscating his effects, and these should now, as an act of very tardy justice, be obtained by the present Government and handed over to Mr. Jim Kelly, as Ned’s sole surviving next of kin.

It is to be hoped that, though belated, retribution will yet be made to the next of kin — Mr. Jim Kelly, of Greta, the only surviving brother of Ned Kelly. It may incidentally be mentioned that Mr. Jim Kelly is a well known and very highly respected resident and farmer of Greta, and the author has the greatest possible pleasure in having produced this book, vindicating the memory of his famous brothers and all the members of his family.

THOMAS CARRINGTON, ARTIST.

Mr. Thomas Carrington, before the Royal Commission, was sworn and examined:—

By the Commission: What are you? — Artist.

Question: You are connected with the press? — Yes.

Question: Were you present at Glenrowan when the Kelly Gang was caught? — Yes.

Question: Is it a fact that the impression you formed from the early portion, say from 3 o’clock till just before the firing of the hotel, was that there was no superior officer taking command and giving any instructions to the men? — That is what it seemed to me.

Question: Did you see Mr. O’Connor at that time? — No.

Question: If you did not see Mr. O’Connor or Mr. Sadleir giving instructions between the hours you speak of, did you see any constables or men giving orders or doing anything as if they were under orders?

Answer: No; I saw Mr. Sadleir during the day, but he was always, when I saw him, in the room with Ned Kelly, cutting up tobacco and smoking, standing by the fire and talking to others. I was in the room three times.

Question: Do you know what time the cannon was sent for?

Answer: I do not. I heard a rumour of a cannon being sent for, but I thought it was a joke; that someone was amusing himself. The idea of a cannon to blow two lads out of a house seemed to me something very remarkable — a house surrounded by something like fifty men armed with Martini-Henry rifles.

Question: You say lads — how do you know there were but two?

Answer: We were told that Byrne had been shot while drinking whisky, and Ned Kelly was a prisoner.

Question: Who told you Byrne was shot?

Answer: Nearly everyone that came out of the hotel.

Question: Did you hear Ned Kelly say so?

Answer: No.

Question: Was it generally believed by those present that Byrne had been shot?

Answer: Yes.

Question: It was an established fact?

Answer: Yes, it was circumstantially told that he was shot, drinking a glass of whisky, and that the other two were standing in the passage — that was what twenty or thirty men said coming out, that the other two were cowed — were standing in the passage frightened, and then when I heard about the cannon to destroy those two lads I looked upon it as a joke.

Question: Is the Commission to understand that really your impression is that had any officer been present after Mr. Hare had to retire, in consequence of the shot, those outlaws could have been captured much earlier in the day, and without the burning of the hotel?

Answer: My idea is this, that if anybody had been there to take up the command, after those four outlaws had come out and emptied their weapons, and called on his men to rush in, they could have taken them easily. They were all outside the hotel when Kelly was wounded.

Answer: I am perfectly certain they could, because the house towards the Benalla end was a blank wall. There was a door here and there, a small passage and a blank wall the other side. The men could have come up to this side and rushed round simultaneously.

Question: Those blank sides are the chimney end?

Answer: One is the chimney end; they are both blank ends. They could come up this way, open out and take the house in front and rear (pointing to the plan), besides there was (Ned) Kelly’s armour on the platform. If it was good enough for him to face the police with, surely someone could have put it on and have gone in, besides with the knowledge that the only two left in the place were the youngest, and they were both cowed and frightened, and both in their armour.

Question: From what you have seen, did you approve of that action of burning the hotel?

Answer: Certainly not — most ridiculous. I never heard of such a thing in my life. Of course, I do not know much about military tactics, but it seemed to me almost as mad as sending for a cannon. If the police had joined hands round the hotel the outlaws could not have got away; they (the police) could have sat down the ground and starved them out.

Question: Did you hear any civilians say they were willing to do it (rush the hotel)?

Answer: I heard two or three working men say, “I would do it if I had some firearms myself. I would rush the hotel myself.”

Question: Did those uncomplimentary remarks apply to the police as policemen or to the officers and their discipline?

Answer: To the police generally — spoke of them as they, “Why do not they rush the hotel?” “Why do not they put on the armour?” and so on.

Question:— About what time in the day did you see the last shot come from the hotel?

Answer: Well, I do not think there were any shots fired after ten. I am not sure, but you could not very well tell, because there was more danger from the police scattered round. The police on the hill might have fired a shot and people have thought it came from the hotel.

Question: Was there danger of the police shooting each other?

Answer: Undoubtedly. I went down during the day to the Beechworth end and knelt behind a log with one of the police, and while we were sitting there — I was making a drawing — a rifle ball came over our heads. I will swear it was not fired from the hotel, because I was looking at the hotel at the time. It must have come from the ranges at the back — the south end.

Dave Mortimer’s Statement.

Statement made, immediately after the burning of the hotel, by Mr. David Mortimer, brother-in-law of Mr. Thomas Curnow, State school teacher, who stopped the police train:

“Our feelings at that time were indescribable. The poor women and children were screaming with terror, and every man in the house was saying his prayers. Poor little Johnny Jones was shot almost at once, and I put my hands in my ears so as not to hear the screams of agony and the lamentations of his mother and Mrs. Reardon, who had a baby in her arms. We could do nothing, and the bullets continued to whistle through the building. I do not think the police were right in acting as they did. We were frightened of them and not of the bushrangers. It was Joe Byrne who cursed and swore at the police. He seemed perfectly reckless of his life. . . . We frequently called on the police to stop firing, but we dared not go to the door, and I suppose they did not hear us. Miss Jones was slightly wounded by a bullet.”

When the midday train arrived from Melbourne it brought many passengers from Benalla and other stations. One passenger, the Very Rev. Dean Gibney, who joined the train at Kilmore East, en route for Albury, also alighted from the train.

Dean Gibney came to Victoria collecting for an orphanage in Perth, and when he heard of the siege at Glenrowan he inquired if there were a Catholic priest there, and on being answered in the negative, he decided to get off at Glenrowan and attend to Ned Kelly, who was said to be dying.

It was Dean Gibney who entered the burning hotel and saved Martin Cherry from being burnt alive by police who had set fire to the hotel.

Source:

J. J. Kenneally, The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers, Melbourne: J. Roy Stevens, 5th edition, 1946 [first published 1929], pages 213-241

[Editor: Corrected “up to his side” to “up to this side”; “Graham-Pole sent” to “Graham Pole sent”. Question marks added after “tell the voice” and “Byrne was shot”. The sentence beginning “The first thing I heard was Steele” appears to be missing the Royal Commission’s question preceding it. Removed second full stop after “cease firing.”.]

Leave a Reply