In the 18th and 19th centuries, printed visiting cards (also known as “calling cards”) were widely used, especially by the well-to-do, when calling upon someone at their home or workplace. Visiting cards featured the name of the caller (later cards included the caller’s address), and could be left at someone’s home to show that the card’s owners had visited (notes could also be written on the cards). They were similar to modern business cards, except that they were commonly used for social purposes. They became quite fashionable, with some later cards featuring fancy designs and illustrations; as a social item, they even became sought after by contemporary collectors. However, the idea of visiting cards was taken one step further with the creation of cartes de visite.[1]

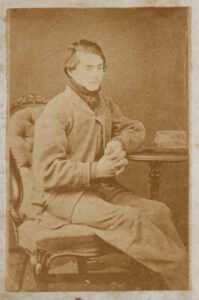

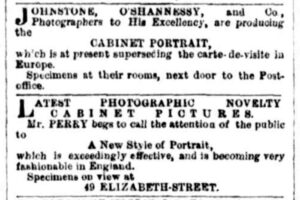

The carte de visite (French for “visiting card”; plural: cartes de visite) was originally patented in 1854 by André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (1819-1889), a French photographer, who struck upon the idea of mounting photographs of people on cards (cardboard mounts), and making them similar in size to visiting cards. He developed a technique of producing multiple images in the same sitting, using a specially-built camera with four lenses and a moving negative plate holder, which could capture eight images on the same plate. His new process lowered costs, making this kind of photography more financially accessible to a wider range of people (especially those of the middle class). Disdéri also coined the term “carte de visite”. The small photographic cards became very popular, even being described as “a cultural sensation”, and the idea spread from France to the rest of the Western world, arriving in Australia in 1859.[2]

The usage of cartes de visite became quite fashionable; although they were not normally used as visiting cards, due to their expense (especially compared to calling cards, printed in a standard fashion). However, like visiting cards, they were traded amongst friends and acquaintances, with collections of these photos being kept by the socially-inclined. Albums were put together of these cards, so that families would have a photographic remembrance of family members and friends. Indeed, albums were manufactured which were specifically designed to hold cards of that size. Susan Long, in The La Trobe Journal (September 2021), says that “The carte album held social currency: who and what were collected were often perceived to reflect the owner’s social status. The album was akin to a 19th-century social inventory.” Cartes de visite featuring famous people were also produced, and were collected by many people. Although the carte de visite fad peaked in the 1860s, they were still popular in the 1870s and 1880s, and even continued to be produced up until the early 20th century (as an indication of their ongoing usage, carte de visite albums were still being manufactured in the 1890s). Their popularity was displaced somewhat by the widespread production of cabinet cards.[3]

The size of the average carte de visite (abbreviated as CdV or CDV) was approximately 6.3 cm. by 10.5 cm. (4.1 inches by 2.5 inches). The size of the photographs used on the cards varied, but they normally took up the majority of the space available. It is worthwhile noting that some photographers cut their own mounts, which added to the minor variations in the sizes of the cards.[4]

Cartes de visite generally have certain distinguishing features which can help to date the cards. Thinner cards were produced in earlier times, whilst thicker cards came later; cards with square corners are likely to have been produced in the 1860s, whilst those with rounded corners date from the 1870s onwards. Borders, backgrounds, and image sizes can also help to date cards. Borders became thicker in later years, decorative backdrops became more elaborate as time went on; earlier photographs were smaller, whilst, later on, the photographs filled up more of the card (with the photographer’s details at the bottom of the card), or even filled up the entire front of the card (with the photographer’s details appearing on the reverse, with earlier ones being rendered in simple text, whilst later ones had the photographer’s details written in very fancy text, sometimes accompanied by some iconography). The clothing and hairstyles of the photo’s subjects can also be useful indicators of when photographs were taken.[5]

To gain an idea of the usage of cartes de visite in Australia over the years, a search was conducted of the historical newspapers on the National Library of Australia’s Trove site for how often CDVs were mentioned in advertisements, as an indicator of their popularity. A search for the phrase “carte de visite” in the “Advertising” category returned the following results:

1860-1869 (12k)

1870-1879 (10k)

1880-1889 (11k)

1890-1899 (1k)

1900-1909 (267)

1910-1919 (46)

Aside from some adverts in 1910 (“8 gem carte de visite miniatures” for 2 shillings), most of the advertisements in the 1910-1919 listings were for carte de visite sized frames, and other non-photo items. That is to say, by 1911 any significant public demand for cartes de visite was finally over. Looking at the years 1880-1887, in the Trove search results, showed listings for 1-2k, whereas the numbers dipped significantly after 1887, with the following three years, 1888, 1889, and 1890, showing results of 480, 431, and 309 respectively (results for 1891-1899 were all under 300, with 1899 at 74). Therefore, 1887 was the last year which showed significant results (in the thousands). The carte de visite format had a great run, with millions of them being produced worldwide; however, their high level of popularity began to dwindle after 1887.[6]

Cabinet cards

Cabinet cards were introduced into Australia in 1866, and were arguably a logical extension of the cartes de visite. They were roughly about two and a half times larger than cartes de visite, and were suitable for mounting on a cabinet or a side table, or could be placed in any other prominent space in one’s home (most likely propped up on a wooden stand, or placed in a photograph frame). The size of the average cabinet card was approximately 10.9 cm. by 16.5 cm. (4.3 inches by 6.5 inches). Cabinet cards were fashionable from the mid-1860s to the 1890s. Their popularity was eclipsed with the advent of snapshots and the rise of the photographic postcard.[7]

Cabinet cards were, in effect, larger sized versions of cartes de visite. However, their prices were correspondingly more expensive than cartes de visite.[8]

Concluding remarks

The age of the carte de visite was a golden age for Australian portrait photography. Distinct from the expensive photography of earlier years, CDVs were within the financial reach of most people. The carte de visite fad left us with a lasting legacy of untold numbers of portraits of colonial and Federation-era Australians. Thousands of these photographs still survive to this day, not only giving us an insight into the fashions and cultural experiences of early Australians, but also providing us with tangible links to our past.

See also:

Cabinet cards

Photography prices (regarding cartes de visite and cabinet cards)

Links to useful information for dating old photographs

Ann Copeland, “Who’s that girl? Dating a 19th century photograph”, State Library of Victoria, 28 July 2021

“Carte de Visite”, Photo Tree

“Introduction to the carte de visite”, The National Science and Media Museum (Bradford, UK), 21 January 2011 [characteristic studio accessories of CDVs and cabinet cards]

Colin Harding, “How to spot a carte de visite (late 1850s–c.1910)”, The National Science and Media Museum (Bradford, UK), 27 June 2013

References:

[1] Michelle Hoppe “Calling cards and the etiquette of paying calls”, Literary Liaisons

Vic, “The etiquette of using calling cards”, Jane Austen’s World, 21 May 2007

Evangeline Holland “The etiquette of social calls & calling cards”, 1 February 2008

“Calling cards”, Story and History: A Guide to Everything Jane Austen, 18 March 2009

Brett & Kate McKay, “The gentleman’s guide to the calling card”, The Art of Manliness, 7 September 2008 (updated: 2 September 2021)

“Gentlemens’ Accouterments”, Georgian Index [includes a photo of a calling card case]

See also:

“Visiting card”, Wikipedia

[2] “Carte de Visite”, City Gallery

“Photographic print type: Carte de Visite (CDV)”, Historical Boys’ Clothing

“carte-de-visite: photography”, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Leslie J. Moran, “A previously unexplored encounter: the English judiciary, carte de visite and photography as a form of mass media”, Cambridge University Press, 23 November 2018 [a cultural sensation]

Susan Long, “Self-representation in the nineteenth century” (The La Trobe Journal, September 2021, pp. 48-59), State Library of Victoria, p. 50 (PDF file) [CDV technical process; CDVs in Australia in 1859]

Stephen Burstow, “The Carte de Visite and Domestic Digital Photography” (Photographies, September 2016), Research Gate, p. 10 (PDF file) [CDV technical process]

“Brady-Handy Collection”, Library of Congress (USA) [CDV technical process]

“March 18: Grace”, On This Date in Photography, 19 March 2017 [CDV technical process; four lenses, eight images on the same plate]

Ann Copeland, “Who’s that girl? Dating a 19th century photograph”, State Library of Victoria, 28 July 2021 [CDVs in Australia in 1859]

“carte de visite”, Merriam-Webster [plural: cartes de visite]

“carte-de-visite”, Dictionary of Archives Terminology [plural: cartes-de-visite]

See also:

“Carte de visite”, Wikipedia

“André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri”, Wikipedia

[3] “My carte-de-visite: A photographic sketch by a man with nerves”, Melbourne Punch (Melbourne, Vic.), 9 March 1865, p. 81 [“they are not visiting cards. I never knew any body who so used them”; expense]

“Carte de Visite”, City Gallery

Colin Harding, “How to spot a carte de visite (late 1850s–c.1910)”, The National Science and Media Museum (Bradford, UK), 27 June 2013

“Carte de Visite”, Photo Tree

“Carte de visite”, Luminous-Lint [albums]

James S. Brust “Filler Cartes de Visite: A fresh look at art, humor and satire”, Military Images Digital, 1 September 2019 [albums]

Susan Long, op. cit., p. 56 [quotation; CDVs peak was 1860 to late 1870s; albums in the 1890s]

See also:

“Cartes de Visite”, Flickr

James Mcardle, “23 October: Evolution”, On This Date in Photography, 23 October 2021 [includes a photo of the back of a proof for a carte de visite, from Stewart and Co. (of Bourke Street, Melbourne), which gives instructions for clients]

Charles Dickens, “The carte de visite”, 26 April 1862, in: Charles Dickens, All the Year Round: A Weekly Journal (vol. VII, 15 March to 6 September 1862), London: C. Whiting, 1862, pp. 165-168 [this article was also published in The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, NSW), 27 October 1862, p. 8; also available at: Dickens Journals Online]

[4] Colin Harding, “How to spot a carte de visite (late 1850s–c.1910)”, The National Science and Media Museum (Bradford, UK), 27 June 2013

“Cartes de Visite”, Luminous-Lint [includes a photo of a carte de visite template]

Notes:

a) The abbreviation of “carte de visite” is commonly rendered as “CdV” or “CDV”.

b) Measurements taken of cartes de visite in the IAC collection give the following results:

width 6.3 cm. = 2.4803149606 inches (2 and 31/64 inches)

height 10.5 cm. = 4.1338582677 inches (4 and 9/64 inches)

There were some minor variations in the sizes of CdVs, so measurements were taken of those cards which were in the majority (in terms of being of similar size). Measurements were taken in centimetres, and were converted to inches using UnitConverters.net.

[5] “Carte de Visite”, Photo Tree

“Introduction to the carte de visite”, The National Science and Media Museum (Bradford, UK), 21 January 2011 [characteristic studio accessories of CDVs and cabinet cards]

Colin Harding, “How to spot a carte de visite (late 1850s–c.1910)”, The National Science and Media Museum (Bradford, UK), 27 June 2013

[6] See: Trove search for “carte de visite” in the “Advertising” category, Trove (National Library of Australia) [results can be sorted by decade, using the “Date range” function; “k” refers to a thousand, or an approximation thereof]

[7] “Cabinet card”, City Gallery [1866; 1924; snapshot]

Colin Harding, “How to spot a cabinet card (1866–c.1914)”, The National Science and Media Museum (Bradford, UK), 5 September 2013 [says cabinet cards appeared in the 1860s; photographic postcard]

Samuel Thomas, “What is a Carte de visite? (1850 – 1910)”, 13 July 2020 [says cabinet cards appeared in the early 1870s]

See also:

“Cabinet card”, Wikipedia

Notes:

Measurements taken of cabinet cards in the IAC collection give the following results:

width 10.9 cm = 4.2913385827 inches (4 and 19/64 inches)

height 16.5 cm = 6.4960629921 inches (6 and 1/2 inches)

In contrast to the CDVs, all of the cabinet cards in the IAC collection are very close to each other in size. Measurements were taken in centimetres, and were converted to inches using UnitConverters.net.

[8] “Photography prices (regarding cartes de visite and cabinet cards)”, The Institute of Australian Culture, 12 May 2023

Leave a Reply