[Editor: This is a chapter from The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers (5th edition, 1946) by J. J. Kenneally.]

CHAPTER XX.

THE CHARRED BODIES.

Very Rev. Dean Gibney’s evidence continued:— “There is one thing which is hardly relevant to the matter. There was a report spread at the time after I had been attending to Ned Kelly. Of course, I was a very considerable time with him before I moved out at all, trying to prepare him for his last hour, because I thought he was in a dying state — the doctor could not give a deciding opinion as to the result. After that I came out and heard there was a report he was cursing and swearing just soon after I came out. I said, ‘My labour is lost if that is the case,’ and I made my way back and asked the policeman in charge of him to tell me was he making use of any bad language or was he disturbed. He said, ‘No,’ and I asked Kelly himself, and he said, ‘No.’ Then I came out and challenged the parties, and said the man was bad enough, and not to tell lies about him, and afterwards I found it had been telegraphed, but these are points that are of no importance. I forgot to mention anything about Cherry, the man that was taken out of the house. I was aware that he was wounded in the house almost from my going there. Some parties met me and told me this man, a platelayer, was shot by the fire of the police upon the house and he was wounded, and I knew from their information that he could not possibly come out, that he was inside incapable of moving himself, and yet they said he had not died. Well, I did not find him in any of these three rooms. I came to where the bodies of the outlaws were, and I had already passed through the house, and it was a party who had been bailed up with him who knew where he was and ran and took him out.”

Question. — From an outhouse? — I fancy so. I believe he would have been burned; that he is the only one that would have been burned alive if I had not come up.

Question. — You mean that he was the only one whose life would have been sacrificed by the effects of the fire? — Yes.

Question. — You saw him when he was brought out? — Yes; I attended to him as well as I could, and administered the sacrament of my own church to him as far as I could.

Question. — He made some remarks? — Not to me. He seemed to be conscious, but not able to speak.

Question. — You said you went in at the front and not at the back; did you not afterwards appear at the front door, and hold up your hands in this manner (explaining by gesture)? — No; it was at the back. When I was going in I held up my hands, and kept my hands in such a position going into the house, so that the parties observing me might perhaps be justified in saying that I came back from the fact that I turned back from the room I first entered, because I was standing between the people and the blaze, and every movement of mine, I believe, they could see with the strong light that was beyond me. They might in the excitement of the time think I came out. I did not come out of the house at the front.

Question. — Did you appear at the door? — No.

Question. — What intimation had the police from the front that it was all over that caused them to go up to the house? — When I saw the others running to the other side, I suppose I called out to the police. They were on my right hand as I went up. After I came out I turned to them and called out. I dare say they were watching anxiously, and the first of that party then came running, and they all rushed after. I did not come outside the house until I came out of the back. The witness withdrew.

The Very Rev. Dean Gibney Further Examined July 6, 1881.

Questioned by the Commission: — Mr. Sadleir, who had charge of the police at the taking of the Kellys, thinks that some of your statements might be prejudicial to him, and he desired some questions to be put to you; and he has given the written questions here so as to elucidate his meaning in any possible way that can be done? — I may remark that if any word of mine would wound, which is not necessary for truth, I hereby desire to record my wish to blot it out.

Question: The Commission considers that you did exactly what was your duty in everything that you said, even if a wrong impression has been created. Mr. Sadleir was not present, and he desires that these questions may be put. That is the whole thing, and we thought it well to have the matter brought under your notice; and we are much obliged to you for coming again. I will just put the questions as they have been written down, and those are the questions you are supposed to reply to.

The first question is: Were you aware before your arrival at Glenrowan on June 28, 1880, that all the innocent persons except Cherry had left Mrs. Jones’ two hours or so before? — I was aware on my arrival there. I became aware of it soon — at least that the innocent people had been allowed to remove from the house some time about half-past nine or ten o’clock — some two hours before I came that would be; but I heard there was one wounded man there. I believe it was Cherry.

The second question is: When did you learn that I was (that is, Mr. Sadleir) the principal officer on the ground, and where was I then? — I could not say for certain whether I learned the name of the officer in charge before the time the Kellys’ sister came on the ground. Then I knew for certain, as I made inquiries in order to find the officer in charge.

The second portion of the question is: And where was Mr. Sadleir then — I was directed to Mr. Sadleir then by parties on the cordon, the line of the police in the direction in which I found that Mr. Sadleir was not then.

The third question is: Where were you mostly from your arrival at twelve o’clock until the time approached when the house was set fire to? — I might have been perhaps an hour, or it may be more — an hour and a half, perhaps — in attendance on Ned Kelly. In my endeavour to get to him I was, perhaps, ten or fifteen minutes before I could get in, and then I was, I dare say, three-quarters of an hour with him, attending to him with my own duties. It might be more, but I believe it was not short of that time. After that time I went over to the hotel on the opposite side and spent about perhaps five or seven minutes there; it might be more. I met a reverend gentleman there of the Church of England (Rev. Mr. Rodda), and we walked down to where the line of railway had been torn up, and then came back to the railway station.

The fourth question is: Do you remember seeing me (Mr. Sadleir) about the platform? — After the house had been set fire to, I believe I saw you twice. I said I saw you. I believe it was pointed out that that was Mr. Sadleir on the left-hand side of the house looking at the house from the direction of the railway gate. I saw you there with a party of men, and then I sent Miss Kelly to go on now and ask if she might go to the house.

The fifth question is: How long before the house was fired did Mrs. Skillion or Kate Kelly, Ned Kelly’s sister, arrive on the ground? — It was Miss Kate Kelly. Mr. Sadleir, I never saw her; I saw Mrs. Skillion approaching and turned her from the house.

Question — Mr. Sadleir: My question is to elicit who was the woman approaching the building — that is the one I refer to? — I never had any doubt it was Kate Kelly.

Mr. Sadleir — My question is with regard to the woman that approached the building from the railway gates. — It does not matter if we both understand we mean the same person.

Question by the Commission (to the witness): You sent on the sister to Mr. Sadleir, and I think what the Commission have to do is to ask how long before the fire was it she went to Mr. Sadleir? — I believe the man had already come back from the house. I think he had already returned from the house — the one that set fire to it.

Question: It was just at the time the house was set fire to? — I was coming round with this woman to find Mr. Sadleir. I saw the man running from the house after setting fire to it. It was only then I became aware the house was being fired; when I made an effort to get this woman to approach the house I did not know then the house was being fired, but I had heard that there was a cannon on the way.

This is question six: In the interval between her arrival (Ned Kelly’s sister) and your approach to enter Mrs. Jones’ house did you see me (Mr. Sadleir)? — Not at the time that I was called out to; that is, I did not see to take notice until the time I was called out to by Mr. Sadleir that I should not approach there without his permission, or some words to that effect.

Question seven: Please to describe where you went to search for me, and say whether this was after Mrs. Skillion’s arrival or not? — That is a question I have already answered.

Question eight: How long were you detained altogether before your ministrations to Ned Kelly were completed — That is difficult to answer.

Question nine: Was it not possible that while you were so engaged, or even before your arrival on the ground, or after that, the police were acting under definite orders without your knowledge? — It was quite possible that they might be acting under definite orders. I have not made any remark that I know which would show they were not acting under definite orders. My remark, I think, was to the effect that the only uniformity I observed was in the intermittent firing at the house — that there was uniformity in that. They used to begin at one end of the cordon and fire all round till they reached the other. But what I generally felt impressed with was (as I might say, a post factum witness of the scene) that firing had commenced at the house when I believe it ought not to have been done — that is, when all the innocent people were there. I maintain that as it was the practice of those men to stick up people wherever they came to, it was not a fair thing to fire into the house while the innocent people were there. This is where, I think, discipline was wanting; and then continuing till the people burst out of the house, and then firing at them as they burst out. I am referring now as a post factum witness — one that came there and heard what had been going on.

Question ten is: Might not the outlaws have been called on to surrender without your hearing? — Quite possibly, but in reply to that I might say that I understand they were called upon — the idea they were called upon — I would look for occasions sufficiently long for them to see that they were not fired on. I would look for periods of time to be given them to come. Of course, I cannot say exactly what length of time there would be, or what time there was between one volley and the other. I can simply give my impressions in the evidence I give.

Question eleven is: Please to describe the particulars in which you observed the want of generalship, bearing in mind that the outlaws were in impenetrable armour, and the difficulty of knowing in what part of the building they were hiding? — I think I have already answered that question in my general remark upon the way the thing, just as I came there, impressed me, and it was continued while I was on the scene. I look upon the matter as being one which began in a blunder (I am simply stating my impressions), and that it was continued on until they were allowed to go beyond the bounds of the house they were confined to. Some described their condition — lying on the ground. Reardon described the condition of the women and children on the ground, and he was there until someone threatened to kill him by firing on him if he stopped; and then there was such an uproar on the part of the people confined in the place that at length they were allowed to come out and throw themselves on the ground. Now, I could not for the life of me make out how it was possible that the people would be confined to the house for so many hours, and the police would be surrounding it, and that they would not have known the condition of affairs in that house.

Question by Mr. Sadleir: What do you mean by the beginning? — I refer to the volleys that were fired on that house while the people were confined in it.

Question: Does that include the first attack? — Well, I dare say it will. There were more innocent people in that house than there were guilty, and if the police were to fire indiscriminately on us here what would we say?

Question by the Commission: When the first attack was made, you understand, we have it in evidence the police did not know that there were people in the house, and the first volley was fired from the house upon the police — you would not have such a strong opinion as to the first attack on the house? — Surely no one could have any misgiving about Mrs. Jones and her family being there.

Question: This was the first five minutes, when Mr. Hare rushed up and the order was given to cease firing and surround the house; you mean after they knew that the people were in it? — It was considerably before I came there; but I remarked already that I formed my opinions as, I might call myself, a post factum witness.

Question: You simply said there should not be indiscriminate firing upon the house when there were only two outlaws and a lot of innocent people in? — If there was one innocent life to be lost amongst them, I would say the guilty ought to be spared for the sake of the innocent.

Question: Do you think there was any chance of the outlaws escaping at all if there had not been a shot fired after you came? — I thought a guard might have been kept around the place, and the outlaws kept there without firing a shot, and in that condition it would have been impossible for them to have escaped.

Question by Mr. Sadleir: Not even in the darkness of the night? — Well, it would be hardly my place to say what would be another person’s disposition in the matter, but I simply say my own.

Question: Are you making allowances for the darkness that men might crawl through the fence and might be mistaken for one of the guards? — If we had left them stay after daylight, would there not be a possibility of escape? — Then there would certainly have been the possibility.

Question by the Commission: We have it on evidence from Mr. Hare’s official report that there was a very large number of prisoners confined at the house when they went to it at the first moment. Bracken, when he came down to tell about the Kellys, told them also that they had a very large number of people there. He said, “Mr. Hare, I have just escaped from Jones’ Hotel, where the Kellys have a large number of prisoners confined.”

There is one more question: What was the condition of the bodies of Dan Kelly and Hart when you touched them? — Were they stiff as if they had been any considerable time dead? — They were not stiff. I took hold of the hand of the one next to me, and it seemed limp, but from the pallid appearance and coldness I thought that it could hardly have been immediately before — only a short time dead; there would not have been such a settled look upon their countenances if they had not been some considerable time dead.

Question: Was the hand cold? — No, I do not feel able to say cold.

Question: Were the flames broken through? — They were. I could not judge of my own feeling in the matter. It would not be well for me to say I could judge of my own touch because I was hot and excited. I am told that a few minutes might cause the appearances that I saw. That is, if those men were in terror for a good while before and lay down, and if they were wounded and lost blood, and so on.

Question: You saw no marks of fresh blood? — No.

To Mr. Sadleir: Is there any other question you wish to put?

Mr. Sadleir: No, I wish to thank Dean Gibney for the trouble he has taken in coming here.

Question by the Commission (to the witness): With reference to seeing Mr. Sadleir at first, what time did you see him? — I saw him to recognise him for the first time when I was going with the woman Kelly in search of him. He was pointed out to me then standing with a party of men on the left-hand side.

Question: That was after the house was set fire to? — It was just as the man came running down. I saw him then again when I was going up to the house, when he called to me to stop in my course; and then I thought I would have gone to speak a word or two with him at that time, only I thought if these men were observing me from within they would say that I was one of the police and was coming with a message from them, and would have been more determined to take me down; that flashed across my mind, and after walking a pace or two towards where Mr. Sadleir was I stopped, and he then kindly gave me leave to go on. The next time I saw him was above at the house, after I had gone through, and he very kindly indeed, without a demur, thanked me for what I had done; for whether those men were burned alive or not, no one would have known if I had not gone in. Then the man Cherry was found; and I moved away from the scene after that, as I have already told you. I met Mr. Sadleir again when I went to attend to Cherry. He wanted me to stay for a moment, and asked me about the condition of the bodies inside; and I said I had to attend to this man and would explain after. In fact, one of my impressions at the moment was that this man was one of the party of the bodies that I met inside, and that he had life in him, and he was taken out, and I said to myself, “Is it possible I did not observe that, because I was certain they were dead?” Again I saw Mr. Sadleir when the whole thing was over, and he took occasion to thank me again; and I considered he was very complimentary to me. He called me by a name I never got before — “a hero!”

Melbourne,

1st July, 1880.D. T. Seymour, Esq.,

Commissioner of Police,

Brisbane.Sir, — I have the honour to report that on Sunday, 27th June, at 7 p.m., I received a letter from Captain Standish (copy attached). I saw Captain Standish about 7.30 p.m., and informed him that I was willing to assist him, but, as I was under marching orders, I should like the Chief Secretary to wire to you, so as to hold me blameless if I should be doing wrong in going. I, with five troopers left here by special train at 10 p.m., en route for Beechworth. We arrived at Benalla at 1 p.m., and picked up Superintendent Hare and six men. From here our train was preceded by an engine, as a precaution. When, upon nearing Glenrowan Station, the advanced engine was observed to have come to a halt, and then we found that a man had rushed out of the bush, and informed the advanced enginedriver that the outlaws had torn up the rails about a mile further on. Superintendent Hare and I consulted, and we decided to draw the train. We went on up to the Glenrowan Station, so as to enable us to get out our horses to ride down to the torn-up rails. While in the act of getting out the horses, a constable named Bracken, who had been stationed at Glenrowan, rushed frantically down to us, and said: “I have just escaped from the outlaws, who are at Jones’ public house; take care or they will be off.” Superintendent Hare and I started at once towards the house, calling the men to follow us; but, owing to the confusion and noise in taking out the horses, I presume, some of them did not at once respond, as only Mr. Hare, myself, three or four white men, and, I think, about two of my boys, were in the first rush. We rushed straight for the house, and, upon getting within about 20 yards of the place, one shot, followed by a volley, was fired at us from the verandah. We returned the fire, and before I could load again Superintendent Hare called out to me: “O’Connor, I am wounded — shot in the arm; I must go back.” I think the whole party were up by this time. I ordered the men to take cover, and I myself dropped down into a creek immediately in front of the front door, and about 20 yards from it; from here I kept a continual fire, until the outlaws were obliged to retire into the house; the others kept firing also.

I then heard the cry of a woman in the house, and cried out, “Cease firing,” which cry was taken up by us all. I sang out, “Let the women out,” and they immediately came, and passed to the rear. Superintendent Hare, after stating he was wounded, retired to the railway station, and in about 15 minutes went off in the engine to Benalla, leaving me as the only officer on the ground in charge.

I kept my position, and in fact, shot Joe Byrne before we were reinforced, or (of course we cannot say who shot Joe) before another officer arrived upon the ground, which happened at about 5.30 a.m., when Mr. Sadleir arrived with reinforcements from Benalla, thereby leaving me with only 12 men, viz., five boys and seven white men, from 2.30 until 5.30. During this interval I think I may say the heaviest of the fighting was. Of course it is unnecessary for me to give my opinion upon the conduct of Superintendent Hare, in running away to Benalla; I leave you to form your own opinion, when I tell you his wound is only through the wrist. Mr. Hare was only on the ground about three minutes. Ned Kelly, it appears, after going into the house, left by the back door, and was captured a few yards from the building. We then (Mr. Sadleir and myself) thought of rushing the house; but a senior-constable proposed to fire the building, which was done, and, at about 4 p.m., we took out of the house the charred remains of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart, and at the same time we recovered the body of Joe Byrne (about 4 p.m.), but not touched by the fire.

I will communicate further with you, as I see the credit which our party fully deserve the Chief Commissioner is reluctant to give to us.

Your obedient servant,

STANHOPE O’CONNOR,

S. Inspector.

Mr. D. T. Seymour’s reply to Mr. Stanhope O’Connor:—

Brisbane,

15th July, 1880.Sir, — I beg to acknowledge the receipt of your communication of the 1st July, giving an account of your proceedings during the encounter between the police and the outlaws at Glenrowan on the 27th June ultimo, and I regret exceedingly that, so far as I can judge from the very meagre information contained in your report, and the more fully detailed accounts given by newspaper correspondents, I am unable to find any cause for congratulation.

Your report, and that given by the correspondent of the “Argus,” who, it appears, was on the ground, differ widely on some very material points, and it will be a source of great gratification if you are able, as I trust you will be, to show that yours is the correct version.

The portions of the proceedings which chiefly call for explanation are:—

1st — The apparent total absence of discipline or plan by which the affair was conducted from commencement to finish.

2nd — The indiscriminate firing which was permitted, whereby the lives of innocent persons were endangered, and, as it afterwards turned out, were sacrificed; and

3rd — The seemingly unnecessary burning of the premises in which the outlaws and others had taken shelter.

In your report you state that upon Constable Bracken’s arrival with the information that the outlaws were in Jones’ public house you “started off, at once towards the house, calling the men to follow,” etc., but “owing to the confusion and noise in taking out the horses, some of them did not respond;” and you THINK about two of your boys were with you. How did you propose to capture the outlaws without your men; and under whose command were those who were left behind? It seems that each man was left to act as he thought fit — no definite plan of action having been decided upon, and the same want of management appears to have continued throughout.

With reference to the indiscriminate firing which is alleged to have taken place, your report is that “upon getting within about 20 yards of the place one shot, followed by a volley, was fired at us from the verandah; we returned the fire,” etc., and a little further on you continue: “I kept up a continual fire until the outlaws were obliged to retire into the house. I then heard the cry of a woman in the house, and I cried out ‘Cease firing.’ I sang out: ‘Let the women out,’ which was done, and they immediately came, and passed to the rear.”

The “Argus” report of this portion of the affair is very different; it runs thus: “The police and the gang blazed away at each other in the darkness furiously; it lasted about a quarter of an hour, and during that time there was nothing but a succession of flashes and reports, and the pinging of bullets in the air, and the SHRIEKS OF WOMEN WHO HAD BEEN MADE PRISONERS IN THE HOTEL”; and again: “At about eight o’clock in the morning a heart-rending wail of grief ascended from the hotel. The voice was easily distinguished as that of Mrs. Jones, the landlady. Mrs. Jones was lamenting the fate of her son, who had been shot in the back, as she supposed, fatally. She CAME OUT OF THE HOTEL CRYING BITTERLY, and wandered into the bush on several occasions”, etc. “She always RETURNED, however, to THE HOTEL,” etc. How do you reconcile this statement with your report? But, supposing the “Argus” version is incorrect, the matter is in no better light. The number of occupants, whether voluntary or compulsory, the strength and condition of the outlaws, the position of the passages and doors, and all information requisite to ensure the capture could have been obtained from Constable Bracken, who had himself been a prisoner, had a little more coolness and judgment been exercised on arrival at Glenrowan.

When the premises were set on fire, it appears that an officer of the Victorian police was present in command; you had, therefore, nothing to do with that matter, but it would have given much satisfaction here had you objected to such a course, which hardly seems to have been requisite when so large a body of police was present.

In replying to this letter, which you will be good enough to do without delay, you will be careful to abstain from all reference to others, further than stating any orders you may have received.

All that I have to do with is the conduct of yourself and the troopers placed under your charge.

I have the honour to be, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

(Signed) D. T. SEYMOUR,

Commissioner of Police.

A large crowd came on the scene from Benalla by the midday train. A party of three young men from a distance noticed a grey horse on the hill behind McDonald’s Hotel with something like a lady’s riding-skirt hanging from the saddle; they hastened to the spot and discovered that it was one of the Kelly’s pack horses, and that it was a blanket which was hanging from the pack saddle. With a constable, who had just arrived on the scene, they removed the saddle and examined the pack. They found, among other things, a small oil drum containing blasting powder, and about 30 feet of fuse, and a complete kit of tools for shoeing horses. The Kellys were very practical men, and always shod their horses at home and on the track. The powder and fuse was intended for use on the railway line to prevent the train returning to Benalla against the wishes of the bushrangers. Even after the shooting of the horses of law-abiding citizens, the fifty police did not consider themselves competent to prevent the two youths from escaping on foot.

Now let us compare the record of Ned Kelly and the record of the police with the approval of the Government of the Colony of Victoria during the ’sixties, ’seventies, and up to the Police Purge of 1881.

NED KELLY’S RECORD.

(1) At the age of 15 years he was charged with holding the bridle reins of a bushranger’s horse. — Discharged.

(2) At 16 years old convicted with a sentence of six months re the McCormack affair, considered by the public as an outrageous Miscarriage of Justice.

(3) At 16 years old convicted and sentenced to three years; proclaimed by the public as a most outrageous Miscarriage of Justice.

(4) At 23 charged with drunkenness, riding across a footpath, and resisting the police. Fine and costs amounted to £3/1/-, which was paid. This was the only genuine conviction recorded against Ned Kelly before being driven to the bush.

POLICE AND GOVERNMENT RECORD.

(1) 1028 Loaded Dice by Assistant Chief Commissioner C. A. Nicolson. Bring the Kellys up on any charge, no matter how paltry.

(2) Compounded a felony — horse-stealing by Aaron Sherritt.

(3) Compounded a felony — sheepstealing by John Sherritt — which apparently qualified the latter as bad enough or good enough to be accepted into the Police Force.

(4) Violation of the Liberty of the Subject — arresting without evidence of any charge, without the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act, 22 Freemen.

(5) Illegal confiscation of Kelly Gang’s property — the armour, green silk sash, &c.

(6) Illegally poisoning farmers’ dogs.

(7) Allowing a bitterly biassed judge to try Ned Kelly for his life.

(8) Refusal by the biassed judge to state a case for the Full Court on objections raised by Ned Kelly’s counsel to the illegal manner in which the trial was conducted and the admission as evidence of hearsay statements.

(9) The failure of the Royal Commission (six of whom were members of Parliament) to condemn the illegality of arresting 22 free men without evidence of any charge against them and without the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act.

NED KELLY’S TRIAL AT BEECHWORTH.

Martin Cherry died shortly after Rev. Dean Gibney had administered the last sacraments of the Catholic Church to him. His body was handed over to his sister by Supt. Sadleir, who wrote an official report, in which the following diabolical concoction appeared:—

“It was known at this time that Martin Cherry was lying wounded in a detached building, shot by Ned Kelly early in the day, as it has since been ascertained, because he would not hold aside one of the window blinds; and arrangements were made to rescue him before the flames could approach him. This was subsequently done.”

The sworn contradiction to this misleading and slanderous official report sent by Supt. Sadleir to headquarters is contained in the following replies to questions put to Supt. Sadleir by the Royal Commissioners, before whom he gave evidence on oath on April 14, 1881. It was not convenient for the Coroner, Mr. Wyatt, to hold an inquest on the bodies of Martin Cherry and Joe Byrne, therefore Mr. Robert McBean, J.P., of Benalla, held a magisterial inquiry (not an inquest).

Question by the Commission: What was the magisterial finding on the case of Cherry?

Supt. Sadleir: Shot by the police in the execution of their duty.

Question: And in the case of Byrne?

Supt. Sadleir: That he was shot as an outlaw. (Although he ceased to be an outlaw on February 9, 1880).

(Although he ceased to be an outlaw before he arrived at Glenrowan on the day before he was shot, because the Outlawry Act had lapsed by the dissolution of the Parliament which passed it. Parliament dissolved on 9/2/1880. Joe Byrne was shot on 28/6/1880).

Question: Who was the magistrate?

Supt. Sadleir: Mr. McBean, J.P.

Question: Do you remember if a party of civilians offered, before the burning of the place, to rush it themselves?

Supt. Sadleir: One did — not to rush it. A man named Dixon [Mr. Tom Dixon, bootmaker, Benalla], a man I have already spoken of, said, “If you will allow me, I will go to the end building and bring out Cherry.”

In answering a previous question, Supt. Sadleir said:—

“I got round the back of the building and found a man named Dixon, a private citizen of Benalla and, I think, three others lifting out Cherry.”

Mr. Thomas Dixon volunteered before the house was set on fire to rescue Martin Cherry, who was lying mortally wounded by police bullets, but Supt. Sadleir would not give him permission to rescue this innocent victim of police bullets.

Supt. Sadleir seemed to be quite content to allow Cherry to be sacrificed, and if Very Rev. Dean Gibney had not gone into the burning hotel in spite of Supt. Sadleir, Martin Cherry would have been roasted alive.

After the fire had died down, the charred bodies of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart were plainly visible; they were removed to the railway platform, and Supt. Sadleir handed them over to Mrs. Skillion and Richard Hart.

To this dramatic close of the Kelly Gang activities now came a most pathetic incident: Mrs. Skillion kneeling between the two burnt bodies, in an outburst of passionate grief, delivered a telling invective on the police, many of whom seemed to have become very much ashamed of the discreditable part they played in the siege of Glenrowan.

There was no inquest or inquiry held on the remains, which the relatives removed to Kellys’ homestead on the Eleven-Mile Creek; coffins for the burial were then obtained from Benalla.

There being no relatives of Joe Byrne present to claim his remains, they were taken by the police to Benalla and secretly buried in the cemetery there. Before the burial, however, the body was tied to a wall and photographed.

Captain Standish disapproved of the action of Supt. Sadleir in handing the bodies of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart to their relatives, and an effort was to be made to take the bodies from them. The relatives vigorously refused to give up the remains of their dead, and made preparations for a determined fight with the police.

Sixteen mounted policemen were despatched from Benalla to Glenrowan to secure these two bodies. They put up for the night at the Glenrowan police barracks, and were expected to go out to the Kellys’ homestead next day and forcibly take possession of the remains of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. Savagery directed by stupidity could not have gone further. The Kelly Gang ceased to be outlaws on 9/2/1880, when the Outlawry Act lapsed, but the police seemed to be ignorant of that fact.

It is true that a warrant had been issued for the arrest of Dan Kelly, provided he could be arrested while he was alive. But there was no warrant now to arrest the body of Steve Hart, and it is only fair to assume that as the authorities were not cannibals, they had no use for them.

A very large number of people attended the funeral of these two youths, who were buried in the Greta Cemetery. The evidence of the Very Rev. Dean Gibney put aside for ever the absurd concoctions which claim that Dan Kelly escaped from Glenrowan, and which formed the subject of a despicable book under his name.

Ned Kelly was removed from Glenrowan by train to Benalla. He was attended by Dr. John Nicholson, who found that he had been wounded in the instep, and also in the right hand and legs, and was very weak from loss of blood. On the following day (Tuesday) the captured bushranger was taken by train to Melbourne. Great secrecy was observed by the police in the arrangements made to remove Ned Kelly from the train to the Melbourne Gaol. A great crowd collected at Spencer-street railway station, but the police, fearing trouble, arranged to have him removed secretly from the train at North Melbourne. He was taken from the train to the Melbourne Gaol, while a great crowd of people were anxiously waiting the arrival of the train at Spencer-street. Ned Kelly was placed in the gaol hospital, and on account of the seriousness of his wounds he was unable to appear in court.

When his wounds had healed he was taken in chains under a very strong escort to Beechworth, where he was charged before Mr. Foster, P.M., with the murder, on October 26, 1878, of Constable Lonigan at Stringybark Creek. Ned Kelly was still suffering from the effect of his wounds, but to such an extent had official callousness developed that his sister, Mrs. Skillion, was not permitted to see him. She had been informed that Ned was in need of a change of underclothing; and promptly purchased what was required, but the Beechworth Gaol authorities would not allow the clothes to be given to Ned Kelly. Mrs. Skillion then offered to go with one of the gaol officials and make similar purchases again, and suggested that the officials should take the clothes from the shop, and that she would not do so much as touch the articles purchased. Even this offer was refused, and Ned Kelly, on trial for his life and suffering from the effects of his wounds, was denied a change of underclothing by the gaol authorities.

Mr. David Gaunson, who defended Ned Kelly at his trial, was permitted to have an interview with him in the Beechworth Gaol, in the presence of gaol officials. In the interview Ned Kelly said: “I can depend my life on my sister, Mrs. Skillion. I have been kept here like a wild beast. If they were afraid to let anyone come near me, they might have kept at a distance and watched; but it seems to me to be unjust, when I am on trial for my life, to refuse to allow those I put confidence in to come with in coo-ee of me. Why, they won’t so much as let me have a change of clothes brought in!

“When I came into the gaol here they made me strip off all my clothes, except my pants, and I would not do that. All I want is a full and fair trial, and a chance to make my side heard. Until now the police have had all the say, and have had it all their own way. If I get a full and fair trial, I don’t care how it goes, but I know this — the public will see that I was hunted and hounded from step to step; they (the public) will see that I am not the monster I have been made out. What I have done was under strong provocation.”

During the trial of Ned Kelly at Beechworth (at the conclusion of Constable McIntyre’s evidence), Mr. D. Gaunson again made application to Mr. Foster, P.M., that Ned Kelly’s sister, Mrs. Skillion, be permitted to see him.

Mr. Foster afterwards told Mr. Gaunson that under no circumstances could the application be entertained. And yet the people of Victoria have been frequently told that in every Court of British Justice the prisoner is always assumed to be innocent of the charge for which he is being tried until he has been fairly and justly tried and convicted by an unpacked jury of his peers.

This is the same Mr. Foster, P.M., who illegally and unlawfully kept a number of Kelly sympathisers in the Beechworth Gaol from January 2, 1879, to April 22 of the same year, without any charge or complaint being laid against any of them, or any evidence heard to justify Foster’s action.

The attitude of Mr. Foster on this occasion was a further demonstration of the fact that, in the so-called judicial mind, Ned Kelly had already been convicted, and his alleged trial was but a very formal affair.

Mr. Foster did not in any way comment on the very serious disparity between the evidence now given by Constable McIntyre at Beechworth and that given by him at Mansfield at the inquest on the bodies of Constables Scanlan and Lonigan on Monday, October 28, 1878. Mr. Foster committed Ned Kelly to stand his trial at Beechworth for the murder of Constable Lonigan.

The treatment meted out to Ned Kelly at Beechworth by the gaol and judicial authorities aroused a great deal of sympathy for him in the public mind, and the Government of the day, fearing that a Beechworth jury would not convict him, changed the venue of his trial from Beechworth to Melbourne.

HOW NED KELLY WAS TRIED AT MELBOURNE BY SIR REDMOND BARRY, WHO, AT BEECHWORTH, SENTENCED HIM TO 15 YEARS, THOUGH NOT CONVICTED, TRIED, CHARGED, OR ARRESTED.

FRIDAY 15TH OCTOBER, 1880.

Mr. H. Molesworth applied for a postponement of Ned Kelly’s trial until next month. In support of the application, he read the following affidavit made by Mr. David Gaunson:—

I, David Gaunson, of 17 Eldon Chambers, Bank Place, Melbourne, attorney for the above-named prisoner, Edward Kelly, make oath and say:—

(1) That the friends and relatives of the prisoner have not been allowed the usual access to the prisoner as a person awaiting trial, and the prisoner has thereby been greatly embarrassed in preparing his defence.

(2) That the prisoner has been unable to provide the necessary funds for counsel, and I have therefore not delivered any brief.

(3) That the depositions are very voluminous, and in order to defend the prisoner I believe counsel will need an adjournment till the next sitting.

(4) That I am informed, and believe, prisoner’s sister had arranged to borrow money for her brother’s defence on land occupied by her, but on applying to the person who had promised her the loan, she found that the Government had confiscated the land.

(5) That on enquiry at the Lands Office Department, I found that this week the prisoner’s mother had a selection under the amending Land Act, 1865, on which she had paid up all the rents under her seven years’ lease. That she had borrowed money from the Land Credit Bank, Melbourne; that the bank sold her interest to prisoner’s sister, but that the Lands Department, on the application of the police, had refused to grant the title to the land.

(6) That I therefore applied to the Minister of Lands, pointing out the injustice done in the Crown forfeiting the 14/- per acre paid on account of such land, and I have reason to believe that if this trial be postponed till next sitting that the title will be completed, and money raised on such land for the purpose of defending the prisoner.

(7) That the want of means has so embarrassed both the prisoner and myself in preparing a defence, that I can safely say that, in my judgement and belief, the prisoner will be unable to obtain his counsel and be seriously prejudiced in his defence if his application for a postponement be refused.

His Honor, Mr. Justice Barry, said no reasons founded on justice or principle had been given in support of the application being granted. Applications of this character were never refused except on substantial grounds, but in this case there was no reason for supposing that if the trial were postponed money for the defence of the prisoner would be raised in the meantime. He could not assume that the land had been confiscated improperly, for there was an Act of Parliament under which the proceedings would have to be guided, and as the grounds for the present application were vague, inconsistent and wholly unauthorised, he would refuse it. The Act of Parliament above referred to lapsed on the 9th February — eight and a half months before the above application was made.

Application refused.

Monday, October 18, 1880.

Mr. Bindon (counsel for Ned Kelly) said he had, on behalf of his friend Mr. Molesworth, an application to make to the court. It was, in fact, that the trial of the prisoner might be postponed until the next sittings, and he made a motion on the grounds contained in an affidavit sworn by Mr. David Gaunson, the prisoner’s attorney, of which the following is a digest:—

“That an unsuccessful application having been made on the 15th instant to postpone the trial, an appeal was made to the Crown to supply funds for the defence, and Mr. Gaunson urged, in view of the length and importance of the case, counsel’s fee should be fifty guineas.”

“The sheriff replied, instructing Mr. Gaunson to undertake the defence on the usual conditions, viz., £7 /7 /- for attorney and £7 /7- for counsel, with 5/- for clerk’s fee. The Crown Law officers would decide as to the amount of remuneration, if any, beyond that amount. The depositions in the two cases extend to eighty-five pages of brief paper, and in addition to fully acquainting himself with them, counsel would require to read the voluminous newspaper accounts of Euroa, Jerilderie and Glenrowan affairs, referred to in the depositions, and to study the law to see how far the Crown can get into them. An adjournment to next sittings was, therefore, applied for.”

Mr. Smyth (for the Crown), after going into details, said: Although opposing the application, he was loth to do anything which would convey an impression that the prisoner had been improperly treated; and if his Honor thought a case had been made out that he ought not to oppose it, he would not do so. If his Honor could, therefore, adjourn the trial until Monday next, he, (Mr. Smyth) said he would not object to that course being pursued.

His Honor said that he would not be disengaged until the 28th instant. Mr. Smyth said that date would do, and the trial was accordingly postponed until Thursday, 28 instant.

DID NED KELLY GET A FAIR TRIAL FROM JUDGE SIR REDMOND BARRY?

Thursday, 28 October, 1880.

The Crown appeared to be thirsting for Ned Kelly’s blood, and provided an exceptionally strong bar to secure a conviction.

Mr. A. C. Smyth, with Mr. Chomley, prosecuted on behalf of the Crown, and Mr. Bindon, instructed by Mr. D. Gaunson, for Ned Kelly.

They called Detective Ward and Constable P. Day to prove that a warrant had been issued for Ned Kelly prior to the battle of “Stringybark Creek.”

Senior constable Kelly and Sergeant Steele were called to prove the capture of Ned Kelly at the “Siege of Glenrowan.”

Constable McIntyre was the only witness who could give any direct evidence in connection with the charge of murdering Constable Lonigan.

The evidence of the following prisoners at Faithful’s Creek — George Stevens, Wm. Fitzgerald, Henry Dudley, Robert McDougall, J. Gloster, Frank Beecroft and Robert Scott — could not prove that they knew, of their own knowledge, that Ned Kelly shot Lonigan at Stringybark Creek, and such evidence should not have been admitted at all.

The evidence of Constable Henry Richards, E. M. Living and J. W. Tarlton, all of Jerilderie, was intended to prove that they had reliable knowledge that Ned Kelly had shot Lonigan on the banks of Stringybark Creek, although their reliable knowledge was some remarks made by Ned Kelly when at Jerilderie. When Ned Kelly made any remarks which could be used against him these remarks were accepted by the Crown as gospel, but when he made a statement that was strongly in his favour the Crown treated such a statement as a tissue of lies.

Dr. S. Reynolds, of Mansfield, stated in evidence that there were four wounds on Lonigan’s body. The fatal pellet entering the eye pierced the brain.

This closed the case for the Crown.

His Honor: What points do you allude to?

Mr. Bindon: All the transactions that took place after the death of Lonigan which were detailed in evidence.

Judge Barry: I think that the whole was put as a part of the proceedings of the day (when Lonigan was shot).

Mr. Bindon: There was a period, after the death of Lonigan, when no further evidence was applicable.

Judge Barry: The way the evidence was put was that Lonigan was not killed by the prisoner in self-defence.

Mr. Bindon submitted that the only evidence available for the purpose of the prosecution was what had taken place at the killing of Lonigan.

Judge Barry: The point was a perfectly good one if any authority could be shown in support. But he thought the conduct of the prisoner during the whole afternoon after the killing of Lonigan was important to show what his motive was. He must, therefore, decline to state a case.

Addressing the jury, Mr. Smyth (for the Crown) said that, as the motive of the prisoner had been referred to, he thought that when they found one man shooting down another in cold blood, they need not stop to inquire into his motives. It was one of malignant hatred against the police, because the prisoner had been leading a wild, lawless life, and was at war with society. He had proved abundantly, by the witnesses produced for the Crown, who were practically not cross-examined, that the murder of Lonigan was committed in cold blood.

So far as he could gather, anything from the cross-examination, the line of defence was that the prisoner considered that in the origin if the Fitzpatrick “case,” as it was called, he and his family were injured, and that the prisoner was therefore justified in going about the country with an armed band to revenge himself upon the police.

Another point in the defence was that because Sergeant Kennedy and his men did not surrender themselves to the prisoner’s gang, this gang was justified in what they called defending themselves and murdering the police. He asked, would the jury allow this state of affairs to exist? Such a thing was not to be tolerated, and he had almost to apologise to the jury for discussing the matter.

The prisoner appeared to glory in his murdering of the police. Even admitting the prisoner’s defence that the charge of attempting to murder Constable Fitzpatrick was an untruthful one, it was perfectly idle to say that this would justify the prisoner in subsequently killing Constable Lonigan because he was engaged upon the duty of searching for the Kelly Gang. (There was no Kelly Gang when Lonigan was shot.)

It would not be any defence to say that Lonigan was shot by some other member of the gang, because the whole gang was engaged in an illegal act. He thought it was not an unfair inference to draw that McIntyre was kept alive until his superior officer arrived only to be murdered afterwards, and thus not a living soul would have been left to tell the sad tale of how these unfortunate men met their deaths at the hands of this band of assassins. The prisoner wanted to pose before the country as a hero, but he was nothing less than a petty thief, as was shown by the fact that the gang rifled the pockets of the murdered men.

The murders committed were of a most cowardly character, and the prisoner had shown himself a coward throughout his career. The murders that he and his companions committed were of a most bloodthirsty nature. They never appeared in the open excepting they were fully armed and had great advantage over their victims.

Mr. Bindon, in addressing the jury for the defence, said it was his intention, in conducting the case, not to refer to or introduce a variety of matters which had nothing to do with the present trial; but, unfortunately, his intentions were rendered futile by the Crown, who brought forward a number of things foreign to the present case.

The question still remained how far this material was to be used in influencing the jury in arriving at a verdict. According to all principles of fairness and justice, these matters should not have been brought forward, because the only thing that the jury was concerned in was the shooting of Lonigan. With the shooting of Kennedy and the proceedings at Glenrowan and at Jerilderie the jury had nothing whatever to do at present, and he therefore requested them to keep these things from their minds.

In McIntyre’s evidence a long account was given of what took place in the Wombat Ranges, but he would point out that he had appeared on the scene, not in uniform, but plain clothes, and armed to the teeth. An unfortunate fracas occurred, which resulted in the shooting of Lonigan. The point to which he wished to draw special attention was that the only account of the affair came from McIntyre, who was a prejudiced witness. He thought that McIntyre was not a witness who, under the peculiar circumstances, could give an accurate account of what occurred. McIntyre said he was as cool as possible, but he must have been in such a state of excitement that it could not be expected of him to distinguish correctly what actually did take place. Because the Kellys were found in the bush, it did not follow that they were secreting themselves; on the contrary, they were following their ordinary occupations in this solitary part of the country, when they fell in with this armed party of men. The Kellys did not know who these people were, and it was a most dangerous doctrine to rest on the evidence of one man, more especially when the charge was that one man shot another deliberately and in cold blood. The evidence of McIntyre should be received with very great suspicion; and with regard to the confessions of the prisoner made at various times, these were uttered either for the purpose of intimidation or to screen others who were associated with him, and therefore the evidence was of no use whatever in corroboration of McIntyre’s version of the transaction. From that point of view, the conversation was merely illusory in its character. Even assuming McIntyre to be the most virtuous man in the world, it was necessary, under the peculiar circumstances, that the jury should receive his statements with the greatest caution. There were only McIntyre and the prisoner who could now say anything of the affair. The prisoner’s mouth was shut, but if he could be sworn, then he would give a totally different version of the transaction. He asked them not to believe McIntyre’s statement as regarded the death of Lonigan. Of course, it would be nonsense to say that Lonigan was not shot, but the point was by whom was he shot? The deaths of Kennedy and Scanlan were not to be allowed to influence the minds of the jury in arriving at a verdict on the first case. There was no ground for the Crown to say that the police had fallen amongst a lot of assassins. The whole career of the prisoner showed that he was not an assassin, a cold-blooded murderer, or a thief. On the contrary, he had proved himself to have the greatest possible respect for human life. The story of McIntyre was too good to be true. It showed the signs of deliberate and careful preparation, and of being afterwards carefully studied.

He would ask: Would the jury convict a man upon the evidence of a single witness, and that a prejudiced witness? If they had the smallest doubt, he trusted the jury would give a verdict in this case different from that which the Crown expected.

His Honor Judge Barry, in summing-up, said that if two or three men made preparations with malice aforethought to murder a man, even if two out of the three did not take part in the murder, all were principals in the first degree and equally guilty of the crime. They aided and abetted, and were as guilty as the man who committed the crime. The fact that the police party were in plain clothes had nothing whatever to do with the case. The murdered men might be regarded as ordinary persons travelling through the country, and they might ask themselves what right had any four men to stop them and ask them to surrender or put up their hands. These men were charged with the discharge of a very responsible and dangerous duty; they were executive officers of the law, in addition to being ordinary constables, and no person had a right to stop or question them.

The counsel for the defence had also told the jury to receive the evidence of McIntyre with very great caution; but he would go further and hope that the jury would receive and weigh all the evidence with caution. It was not necessary to have McIntyre’s evidence corroborated, and he asked the jury to note the behaviour of McInyre in the witness box, and say whether his conduct was that of a man who wanted to deceive.

It was not necessary for him to go through the evidence, as it was so fresh in the memory of the jury. They were not to suppose that the prisoner was on his trial for the murder of Kennedy and Scanlan. The charge against him was the murder of Lonigan, and the object of admitting the whole of the evidence subsequent to the shooting of Lonigan was to give the jury every opportunity to judge the conduct of the prisoner and his intentions during that particular day. With regard to the other part of the case — the confessions made by the prisoner at various times — they had not alone to consider the confessions themselves, but also the circumstances under which they were made. They were not made under compulsion, but at a time when the prisoner was at liberty, and if he made these confessions in a spirit of vain glory, or with the desire of screening his companions, he had to accept the full responsibility. Counsel for the defence said that the prisoner’s mouth was closed and that if it was not closed he could tell a different story to the one told by McIntyre.

But the fact was that the prisoner’s mouth was not closed. That he could not give sworn testimony was true, but he could have made a statement which, if consistent with his conduct for the last eighteen months, would have been entitled to consideration; but the prisoner had not done so. As to whether the prisoner shot Lonigan or not, that was an immaterial point. The prisoner was engaged with others in an illegal act; he had pointed a gun at McIntyre’s breast, and that circumstance was sufficient to establish his guilt. The jury would, however, have to regard the evidence as a whole, and accordingly say whether murder had been committed. It could not be manslaughter. The verdict of the jury must either be guilty of murder or an acquittal.

The jury retired from the court at ten minutes past five in the afternoon and, after half an hour’s absence, returned with a verdict of guilty.

Upon the judge’s associate asking the prisoner whether he had anything to say why sentence should not be passed upon him, Ned Kelly said:

Well, it is rather late for me to speak now. I tried to do so this morning, but I thought afterwards that I had better not. No one understands my case as I do, and I almost wish now that I had spoken; not that I fear death. On the evidence that has been given, no doubt, the jury or any other jury could not have given any other verdict. But it is on account of the witnesses, and with their evidence no different verdict could be given. No one knows anything about my case but myself. Mr. Bindon knows nothing about it at all, and Mr. Gaunson knows nothing, though they tried to do their best for me. I’m sorry I did not ask my counsel to sit down, and examine the witnesses myself. I could have made things look different, I’m sure. No one understands my case.

The crier of the court called for silence while his Honor passed the awful sentence of death upon the prisoner.

Judge Barry: Edward Kelly, the verdict is one which you must have fully expected.

Ned Kelly: Under the circumstances, I did expect this verdict.

Judge Barry: No circumstances that I can conceive could here control the verdict.

Ned Kelly: Perhaps if you had heard me examine the witnesses, you might understand, I could do it.

Judge Barry: I will even give you credit for the skill which you desire to show you possess.

Ned Kelly: I don’t say this out of flashness. I do not recognise myself as a great man; but it is quite possible for me to clear myself of this charge if I liked to do so. If I desired to do it, I could have done it in spite of anything attempted against me.

Judge Barry: The facts against you are so numerous and so conclusive, not only as regards the offence which you are now charged with, but also for the long series of criminal acts which you have committed during the last eighteen months, that I do not think any rational person could have arrived at any other conclusion. The verdict of the jury was irresistible, and there could not be any doubt about it being a right verdict. I have no right or wish to inflict upon you any personal remarks. It is painful in the extreme to perform the duty which I have now to discharge, and I will confine myself strictly to it. I do not think that anything I could say would aggravate the pain you must now be suffering.

Ned Kelly: No; I declare before you and my God that my mind is as easy and clear as it possibly can be.

Judge Barry: It is blasphemous of you to say so.

Ned Kelly: I do not fear death, and I am the last man in the world to take a man’s life away. I believe that two years ago, before this thing happened, if a man pointed a gun at me to shoot me, I should not have stopped him, so careful was I of taking life. I am not a murderer, but if there is innocent life at stake, then I say I must take some action. If I see innocent life taken, I should shoot if I was forced to do so, but I should first want to know whether this could not be prevented, but I should have to do it if it could not be stopped in any other way.

Judge Barry: Your statement involves wicked and criminal reflection of untruth upon the witnesses who have given evidence.

Ned Kelly: I dare say the day will come when we shall all have to go to a bigger court than this. Then we will see who is right and who is wrong. As regards anything about myself, all I care for is that my mother, who is now in prison, shall not have it to say that she reared a son who could not have altered this charge if I had liked to do so.

Judge Barry: An offence of the kind which you stand accused of is not of an ordinary character. There are many murders which have been discovered and committed in this colony under different circumstances, but none shows greater atrocity than those you committed. These crimes proceed from different motives. Some arise from a sordid desire to take from others the property which they acquired or inherited; some from jealousy; some from a bare desire to thieve, but this crime was an enormity out of all proportion. A party of men took up arms against society, organised as it was for mutual protection and regard for law.

Ned Kelly: Yes; that is the way the evidence brought it out.

Judge Barry: Unfortunately, in a new community, where society was not bound together as closely as it should be, there was a class which looked upon the perpetrators of these crimes as heroes. But these unfortunate, ill-educated, ill-prompted youths must be taught to consider the value of human life. It could hardly be believed that a man would sacrifice the lives of his fellow-creatures in this wild manner. The idea was enough to make one shudder in thinking of it. The end of your companions was comparatively a better termination than the miserable death that awaits you.

It is remarkable that although New South Wales had joined Victoria in offering a large reward for the detection of the gang, no person was found to discover it. There seemed to be a spell cast over the people of this particular district, which I can only attribute either to sympathy with crime or dread of the consequences of doing their duty. For months the country has been disturbed by you and your associates, and you have actually had the hardihood to confess to having stolen two hundred horses.

Ned Kelly: Who proves this?

Judge Barry: That is your own statement.

Ned Kelly: You have not heard me; if I had examined the witnesses, I could have brought it out differently.

Judge Barry: I am not accusing you. This statement had been made several times by the witnesses; you confessed it to them, and you stand self-accused. It is also proved that you committed several attacks upon the banks, and you seem to have appropriated large sums of money — several thousands of pounds. It has also come within my knowledge that the country has expended about £50,000 in consequence of the acts of which you and your party have been guilty. Although we have had such examples as Clarke, Gardiner, Melville, Morgan and Scott, who have all met ignominious deaths, still the effect has, apparently, not been to hinder others from following in their footsteps. I think that this is much to be deplored, and some steps must be taken to have society protected. Your unfortunate and miserable associates have met with deaths which you might envy. I will forward to the Executive the notes of the evidence which I have taken and all circumstances connected with your case, but I cannot hold out any hope to you that the sentence which I am now about to pass will be remitted. I desire not to give you any further pain or to aggravate the distressing feelings which you must be enduring.

Judge Barry then passed the sentence of death, and concluded with the usual formula: “May the Lord have mercy on your soul.”

Ned Kelly: Yes; I will meet you there!

On the 3rd November the Executive Council met and dealt with Ned Kelly’s case. It was decided that the law should take its course, and the date for Ned Kelly’s execution was fixed for Thursday, 11th November.

On Friday night, the 5th November, an immense public meeting was held in the Hippodrome. The interior was packed with 2,500 people, and another 6,000 persons were unable to gain admission. The meeting was very orderly, and was addressed by Mr. David Gaunson and his brother, Mr. Wm. Gaunson. The chair was taken by Mr. Hamilton, and a resolution was moved and seconded “That in the case of Ned Kelly, the prerogative of mercy should be exercised by the Governor-in-Council.” This motion was carried unanimously.

A petition signed by 32,000 adults was presented to the Governor at the meeting of Executive Council on the 8th November. While the petition was being considered by the Governor-in-Council an immense crowd assembled outside the Treasury Buildings. The prayer of the petitioners was refused, and the date of Ned Kelly’s execution was finally fixed for Thursday, 11th November, 1880.

At 10 o’clock on the morning of the 11th November, Colonel Rede, the sheriff, came forward in official dress and demanded the body of Ned Kelly. An immense crowd had collected outside the gaol.

Ned walked calmly to execution, and when passing through the garden in the gaol yard he remarked on the extraordinary beauty of the flowers. He walked firmly after his spiritual advisers, Dean Doneghy and Dean O’Hea. He answered the priests, who recited the litany of the dying. The cap was drawn over his face, and, as the lever was drawn, Ned Kelly’s last words were, “Such is life.”

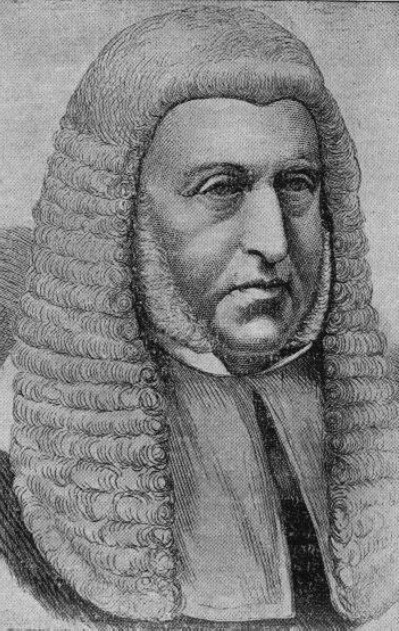

DEATH OF MR. JUSTICE BARRY.

On the 23rd November, Judge Barry died from congestion of the lungs and a carbuncle in the neck. He suffered great pain, but death was unexpected. He survived Ned Kelly by only twelve days, when he was called before that bigger court, where he was sure to get unadulterated justice.

Judge Barry’s unlawful, unjust, and maliciously threatened sentence of fifteen years on Ned Kelly at Beechworth in October, 1878, already referred to, was responsible for the deaths of ten persons. He was responsible for the shooting of the three policemen at the Stringybark Creek; he was consequently responsible for the shooting of Aaron Sherritt; he was further responsible for the shooting of Martin Cherry and Mrs. Jones’ little son at Glenrowan; he was responsible for the deaths of the four bushrangers.

Ned Kelly’s challenge, therefore, to meet Judge Barry where they both would get unadulterated justice was very significant, seeing that Judge Barry was so promptly called to answer that challenge.

On 25th November, Mrs. Ann Jones was charged with harbouring the Kellys and committed for trial.

BIAS OF THE PRESS.

“The Age,” November 12th, 1880:

“Under date 10th November, deceased (Ned Kelly) reiterated in a written statement the greater portion of his first statement. On the third page he says:—

‘I was determined to capture Superintendent Hare, O’Connor and the blacks for the purpose of an exchange of prisoners, and while I had them as hostages I would be safe, as no police would follow me.’

“At the end of the last document prisoner (Ned Kelly) requests that his mother may be released from gaol, and his body handed over to his friends for burial in consecrated ground. [Neither request will be granted.]”

Because Mr. David Gaunson called public meetings for the express purpose of giving the public the actual facts relating to the case of Ned Kelly, and because he had the courage to address these public meetings and liberate the truth so carefully suppressed by the press of that day, the following comments appeared on page 5 of “The Age” of 13th November, 1880:—

“Though the leaders of the Assembly appear to be disinclined to take any measures to purge the House of the disgrace arising from one of its prominent officers exhibiting an active sympathy with a notorious criminal, the constituents of Mr. David Gaunson are not so compliant. A requisition is being signed in Ararat calling upon him to resign his seat. The press thorough the Colony is unanimous in its condemnation of his conduct.

‘The Ballarat Star’ writes:—

“It behoves the Assembly to take immediate steps to vindicate its own honor, which has been sadly besmirched owing to the behaviour of one of its principal officers. The retention of Mr. David Gaunson in the position of Chairman of Committees is an insult, not only to every member of the Legislative Assembly, but an affront to every law-abiding elector in the Colony. Whatever may have been the motives that prompted Mr. Gaunson to depart from the rules that regulate the profession of which he is a member, his conduct in the disreputable affair is equally reprehensible. He seems to have entirely forgotten — if, indeed, he ever realised the fact — that the position he occupies in the Legislative is one of honour, as well as of profit, and that decency of demeanour, both inside and outside the precincts of Parliament, is required on the part of the person who fills it.’

“The ‘Geelong Times’ and ‘The Maryborough Standard’ write in similar strain.”

Source:

J. J. Kenneally, The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers, Melbourne: J. Roy Stevens, 5th edition, 1946 [first published 1929], pages 254-296

[Editor: Corrected: “when the woman approaching” to “who was the woman approaching” (in line with the text on page 165 of the 1969 edition); “Question:: Do you” to “Question: Do you”; “The found” to “They found”; “to torn-up rails” to “to the torn-up rails”; “15TH OCTOBER, 1890” to “15TH OCTOBER, 1880”; “Corpus Act.” to “Corpus Act,”; “I, David Gaunton” to “I, David Gaunson”; “folowing is” to “following is”; “there were uttered” to “these were uttered”; “of an acquittal” to “or an acquittal”; “10 o’clock -on” to “10 o’clock on”; “deceased Ned Kelly)” to “deceased (Ned Kelly)”. Added a single quotation mark after “is the case”; added a question mark after “was set fire to”. Removed second full stop from after “in going.” Added closing bracket after “(about 4 p.m.”. Added closing quotation mark after “several occasions”.]

Leave a Reply